Ancient Greek Murder Victim Died with Weirdly Perfect Circle in Chest

About 2,000 years ago, a heavily muscled man was murdered on a Greek island. The killer drove a seven-pointed spear into the man's chest with such force that it left a nearly perfect circle in his sternum, a new study finds.

Such an injury is rare, said study researcher Anagnostis Agelarakis, a professor of anthropology at Adelphi University in Garden City, New York.

"In my 40 years that I am in the field, I never found something like that," Agelarakis told Live Science. "The way that the [spear's] penetration took place in [reference] to the bone, it is an exact 90-degree angle against the sternum." [Photos: Ancient Greek Burials Reveal Fear of the Dead]

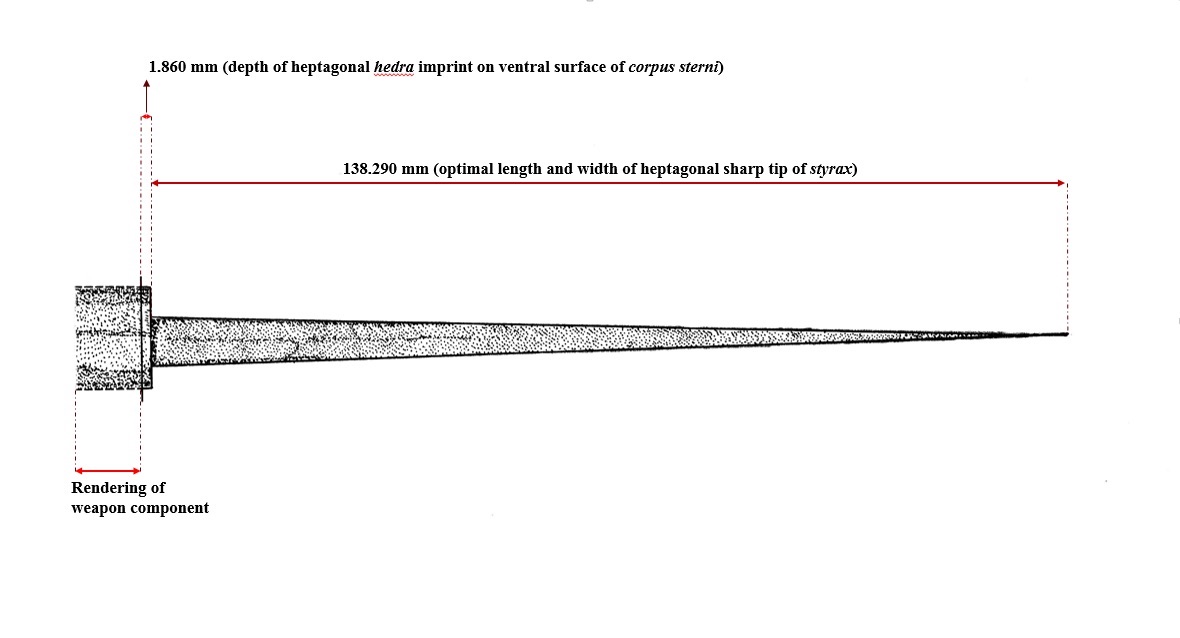

In other words, the ancient spear — known as a styrax, the pointed end of a thrusting spear — wasn't thrown at the victim from a distance. Instead, it was likely thrust inward at close range and done with precision, possibly for an execution, Agelarakis said. An injury like that would have caused cardiac shock and arrest, likely killing the man within 1 minute, Agelarakis said.

Archaeologists found the man's remains in 2002 while excavating a section of an ancient necropolis in Thasos, the northernmost Aegean island. In all, the researchers found the remains of 57 people there. This discovery included the man with the nearly perfect hole in his sternum, who was buried in a "conspicuous limestone cyst [a coffin-like stone box] grave of the Hellenistic period," Agelarakis wrote in the study.

Muscular man

The man was tall for the time period, standing about 5 feet, 7 inches (170.5 centimeters) when he was alive, an anatomical analysis showed. A dental examination revealed that the man was at least 50 years old when he died. Moreover, by studying the marks left by muscles on the bones, Agelarakis determined that the man was muscular during his life.

It's impossible to say how this man became so buff, but it appears he was physically active throughout his life. "He could have easily been somebody who was exercising in the gym, in the palestra," Agelarakis said. It's likely the man also spent ample time swimming and running or even working on tasks relating to the navy, Agelarakis said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, all of these movements, especially repetitive ones, took a toll, as the man's remains showed signs of joint pain and inflammation known as spondyloarthritis, as well as osteoarthritis, Agelarakis said.

Perfect hole

The most intriguing aspect of the skeleton was the hole in the sternum, Agelarakis said. At first, the researcher wondered if it was sternal foramen, a developmental condition that affects about 5% of the modern population, when the sternum doesn't completely form. But the approximately 0.6 by 0.4-inch hole (1.5 by 1.1 cm) wasn't a developmental glitch, but rather a feature created via "penetrating trauma" — likely by a seven-sided styrax, Agelarakis wrote in the study.

With the help of his wife, Argiro Agelarakis, a scientific illustrator and anthropologist who is also at Adelphi, as well as the Adelphi art department, Agelarakis had a few replica seven-sided styrax weapons made out of bronze alloy.

Agelarakis found that when he threw the replicas, they didn't make a perfect circle when they hit their targets, because of the parabolic path they took while flying through the air. So, the styrax likely wasn't thrown at the man, Agelarakis said.

Likewise, the man probably wasn't attacked during a battle or fight, because he would have likely flinched when hit, and this would have made the injury different — that is, not a perfect circle. In all likelihood, the man was likely immobilized — either standing against a wall, kneeling with his hands tied behind his back or lying on his back on the ground — before the styrax was driven into his chest, probably for an execution, Agelarakis said. [In Photos: Spartan Temple and Cultic Artifacts Discovered]

"I concluded that it wasn't something that was hurled but [that] it was something that was steadied first on the sternum and then, with extreme force, penetrated," Agelarakis said.

A few experiments with the physics department at Adelphi University showed that extreme force would have been needed to pierce the man's bone — a force exceeding 2,200 newtons, which is equivalent to about 500 lbs. (227 kilograms) of weight.

It's unclear why the man was executed, but it was probably during a time of political upheaval, perhaps one following military turmoil or reprisals during a regime change, Agelarakis said. A dental analysis showed that just before the man's death, his diet worsened, suggesting that he was a prisoner or captive in his last days, Agelarakis said.

The ancient bones are now being held at the Archaeological Museum of Thasos. The study will be published in a forthcoming issue of Access Archaeology.

- Photos: Ancient Greek Shipwreck Yields Antikythera Mechanism

- Album: The Seven Ancient Wonders of the World

- Photos: Mysterious Ancient Tomb in Amphipolis

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus