Football-Size 'Bugs' Feast on an Alligator in This Creepy Deep-Sea Video

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

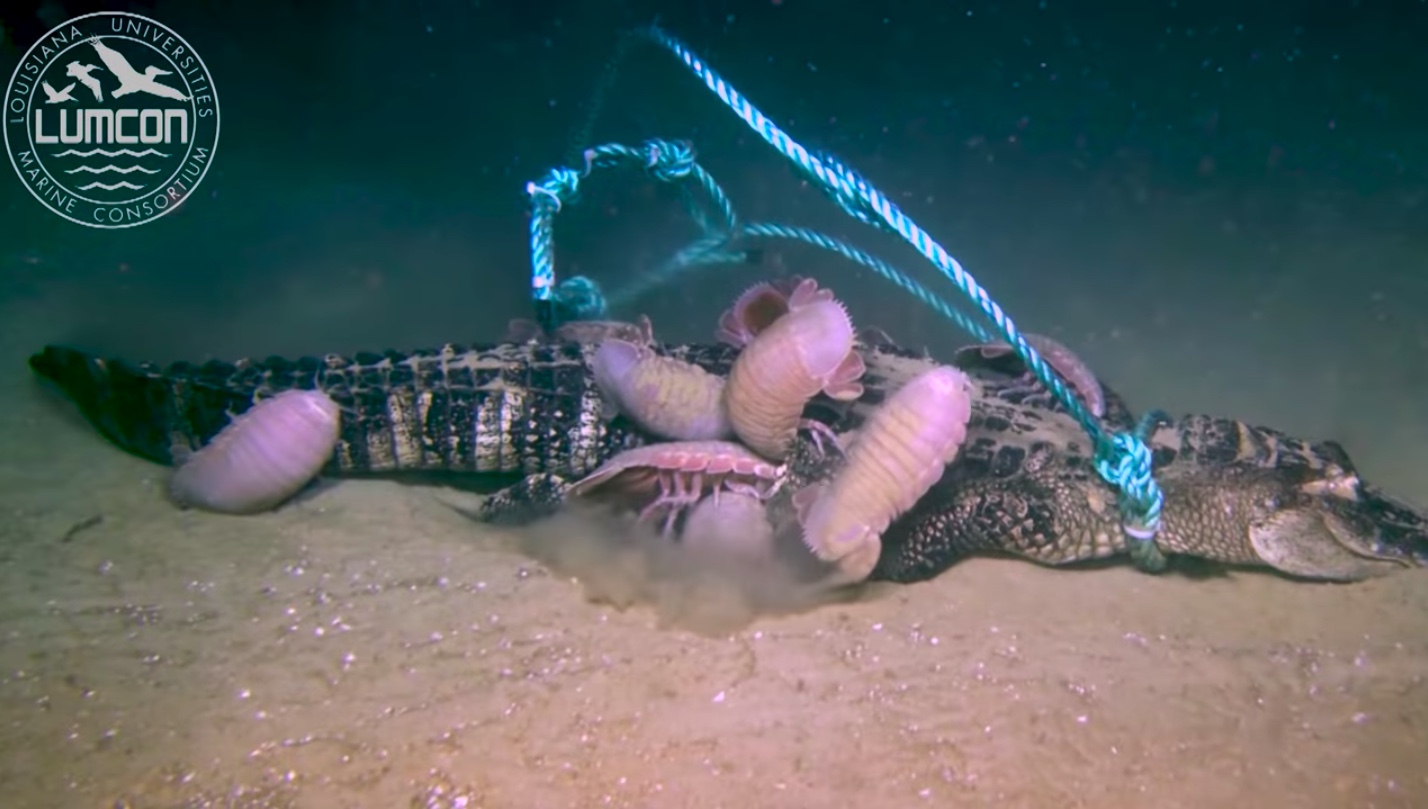

In a creepy video fit for a scene in a horror movie, nightmarish "bugs" that almost look like lobsters emerge on the seafloor to attack the corpse of an alligator, using their mandibles to break through the scaly skin and feed on the juicy insides.

The carcass is lying a mile and a quarter (2 kilometers) down on the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico, and the football-size isopods — they are related to roly polies or pill bugs — are having a field day. These isopods may go for months or years between meals, according to researchers Craig McClain and Clifton Nunnally, both of the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium. [Beastly Feasts: Amazing Photos of Animals and Their Prey]

"They have this amazing ability to gorge themselves, store that energy and then basically not have another meal for months to years afterwards," McClain said in the video.

Gator fall

The alligator came to its watery grave courtesy of McClain, Nunnally and their colleagues, who are interested in studying how "foodfalls" impact marine ecosystems. Foodfalls can be anything from a giant whale carcass to logs of wood (certain clams and specialized bacteria can digest wood) washed into the ocean via rivers. Alligator carcasses may be a common type of foodfall, McClain said, but no one has ever studied them before.

The researchers weighted the carcasses of alligators donated by the state of Louisiana, which humanely euthanized the animals as part of its alligator management program. They then watched on-camera what creatures came to feast.

"The deep ocean is a food desert, sprinkled with food oases," Nunnally said in the video. The gator carcass is a particularly interesting oasis, he added, because alligators are the closest thing alive today to ancient marine reptiles like ichthyosaurs. Some of the creatures that feed on modern alligators could be the same that ate ichthyosaurs millions of years ago, he said.

Easy work

Isopods are crustaceans with ancestors dating back 300 million years. The giant isopods feeding on the alligator seemed well-adapted to their role as scavengers. In less than 24 hours, several were immersed halfway into the alligators' abdomen, chowing down from the inside.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I thought the alligator hide would be something that would be hard to get through, but obviously their pinching and crushing mandibles make easy work of the hide," Nunnally said.

One isopod in the video starts to swim away, only to take a nosedive directly into the sandy seafloor. The animal might be so stuffed with its rare meal that it has trouble moving, the researchers said. [In Photos: Spooky Deep-Sea Creatures]

"We've seen that in other scavengers, where they'll eat so much that they basically become immobile or stupefied in their actions, and so that may just be the fact that they've gorged themselves so much in an effort to get this rare resource that they've actually, you know, inhibited themselves from proper locomotion," Nunnally said in the video.

The project also aims to understand how carbon from land-based life-forms reaches the deep ocean. The researchers set the alligator carcass down nearly two months ago and plan to return to the site later this week. They expect that the carcass will be half gone, and that other scavengers will have moved in to get flesh that the isopods couldn't reach. It's even possible that bone-eating worms called osedax might be found in the gator's skeleton.

"I think it will be interesting to see what new scavengers show up," Nunnally said.

Between April 10 and April 24, the researchers will be tweeting about their discoveries at @LUMCONscience, @DrCraigMc and @seagrifo using the hashtag #woodfall.

- Photos: The Freakiest-Looking Fish

- Photos: Deep-Sea Expedition Discovers Metropolis of Octopuses

- Marine Marvels: Spectacular Photos of Sea Creatures

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus