Sometimes This Comb Jelly Has An Anus. And Sometimes It Doesn't.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Like a rainbow or a sunset, the anus of the warty comb jelly is a fleeting marvel.

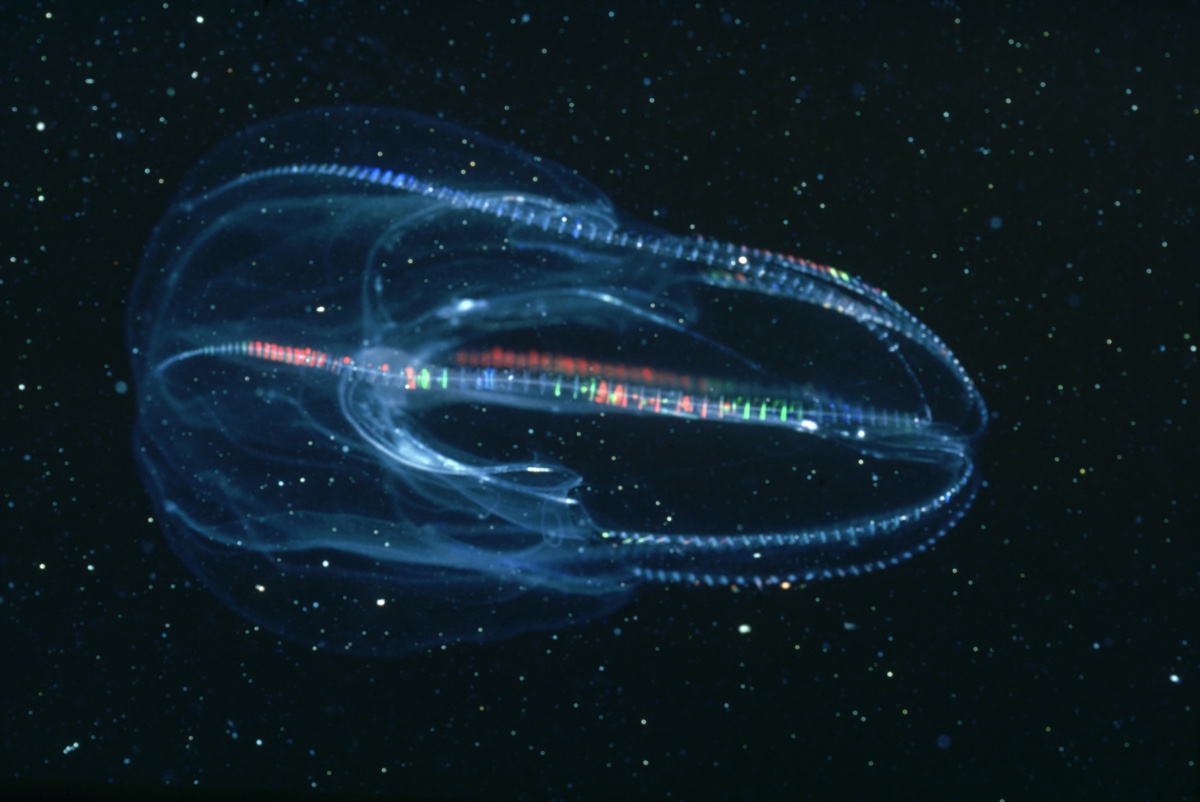

An anus is a gateway for solid-waste removal from an animal's digestive system; in most animals, the anus is reliably found in one location all the time. But Mnemiopsis leidyi, a jellyfish relative that is also known as a warty comb jelly or sea walnut, is not "most animals."

M. leidyi's anus isn't fixed in place on its gelatinous body. Instead of a permanent opening, a so-called anal pore appears when the jelly needs to defecate and then disappears immediately afterward, leaving unblemished skin behind, according to a new study. [Image Gallery: Jellyfish Rule!]

M. leidyi belongs to a group of marine invertebrates called ctenophores (TEEN-oh-fours). Unlike such close relatives as sponges and jellyfish, ctenophores — especially their bodily functions — are poorly understood, Sidney Tamm, a researcher with the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, wrote in the study.

In fact, prior studies had concluded that M. leidyi had a permanent anus. But when Tamm used video microscopy to closely examine M. leidyi larvae and adults, he discovered that their anuses were intermittent, and that the jellies' defecation took place through an opening "which appears and disappears" in a regular rhythm, Tamm reported.

Now you see it; now you don't

After M. leidyi gulps down prey, the meal travels through a six-part digestive system. Eventually, the food ends up in a central stomach that feeds into canals for pooping, which dead-end at the body's surface as lobes, Tamm wrote in the study.

Tamm observed that when a jelly was ready to defecate, the shape of its stomach would change — narrowing into a rectangular box — and its anal canals would widen. Two minutes later, the esophagus "crumpled," preventing more food from entering the stomach. Lobes at the ends of paired anal canals filled with waste particles and began to swell, with one lobe protruding significantly.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As that lobe reached "maximum volume," a pore opened and released a stream of poo as particles and clumps, Tamm reported. But before the pore opened, the skin of that lobe appeared "uniformly smooth," and there was no sign that the pore had opened there before.

Then, when all the waste had been released, "the pore closed completely and disappeared," Tamm wrote. From start to finish, the entire process lasted from 2 to 3 minutes in M. leidyi larvae and juveniles measuring up to 0.8 inches (2 centimeters) long, and 4 to 6 minutes in adults with body lengths between 1.2 and 2 inches (3 and 5 cm).

M. leidyi is to date the only known animal with a "now-you-see-it-now-you-don't" anal pore. Further investigations of its elusive anus may help to explain how permanent anuses evolved in other animals, according to the study.

The findings were published online Feb. 22 in the journal Invertebrate Biology.

- Photos: See the World's Cutest Sea Creatures

- Dangers in the Deep: 10 Scariest Sea Creatures

- Image Gallery: Rich Life Under the Sea

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus