Florida Couple Finds a Grenade. Next Stop: Taco Bell?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

What would you do if you came across a World War II hand grenade? For a Florida couple who stumbled upon a grenade during a fishing trip, the answer was clear: Take it to Taco Bell.

On Jan. 26 at 5:01 p.m. local time, police dispatchers in Ocala, Florida, received a call from a woman who reported that she and her boyfriend had found a grenade while fishing in the nearby Ocklawaha River.

But her story didn't end there. After examining the grenade, the woman's boyfriend placed it in the trunk of her car, and the pair drove to the Ocala Taco Bell, where they notified the police, Ocala Police Department (OPD) representatives posted on Facebook. [7 Technologies That Transformed Warfare]

The couple — Lorena Upton and Charles Carter — were magnet fishing in the river, searching for valuable metal scraps that they could salvage and sell, Officer Jameson Boucher recorded in a case narrative. When Carter fished up the grenade, he put it in a bucket along with the other bits of scrap metal, stowed the bucket in Upton's trunk, and then drove with Upton to a Taco Bell to make the phone call to the police, Boucher said.

Shortly after responding to the call, OPD officers confirmed that the object was in fact "an authentic WWII hand grenade," according to the Facebook post. They swiftly evacuated the restaurant and parking lot, and the Marion County Sheriff’s bomb squad descended on the scene to contain and dispatch the vintage explosive.

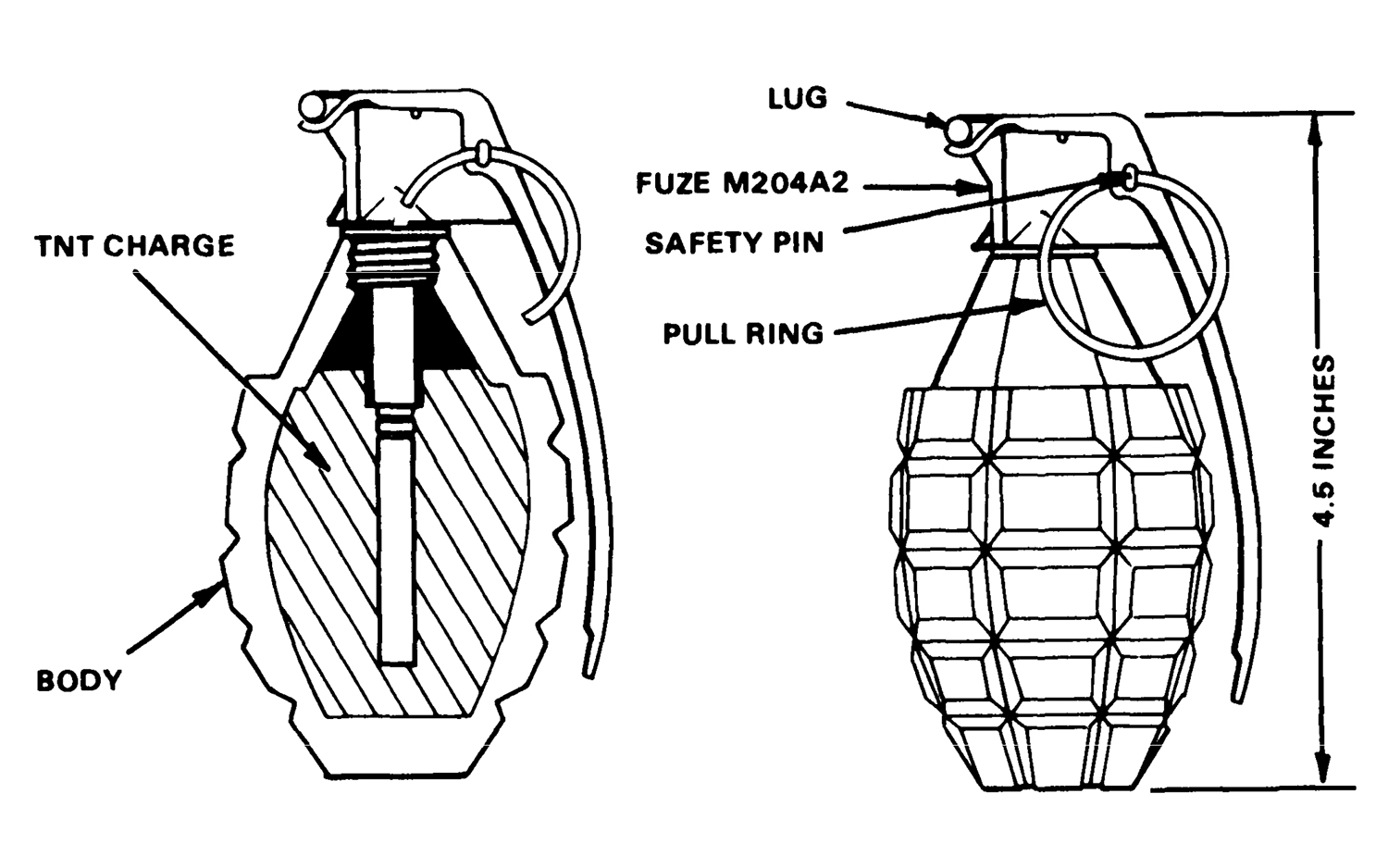

Its corroded shell resembled that of an Mk 2 grenade, a model that was commonly used by American soldiers during WWII and through the Vietnam War, according to the Northwest Florida Daily News (NWFDN). They were also called "pineapple grenades" because of the ridged texture of their bodies, NWFDN reported.

Grenades — small bombs that can be launched or thrown by hand — have been used in American warfare since the Revolutionary War. During that time, spherical, gunpowder-filled explosives helped to turn the tide in favor of the colonists in one of biggest battles at sea, according to the National Museum of American History (NMAH).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One of those Revolutionary War-era grenades, currently in NMAH's collection, was also recovered in Florida.

Hand grenades have three main parts: a body, filler (a chemical or explosive substance), and a fuse that ignites or detonates the filler, according to a 1988 U.S. Army field manual. In the Mk 2 grenade, the filler is trinitrotoluene — TNT — in a cast-iron body; it weighs 21 ounces (595 grams) and has a burst radius of about 33 feet (10 meters), according to the field manual.

While an OPD detective who inspected the grenade said that it did not appear to be functional, as the metal body was highly corroded, the bomb squad technicians proceeded as though the explosive were hot, placing it into a bomb disposal container "so it could be destroyed off-site at a later time," Boucher reported.

Fortunately, the Taco Bell grenade left the scene quietly. Bomb squad specialists removed it from the parking lot "without incident," the Ocala PD informed local residents on Facebook, and the police concluded the day's report with a reassuring four-word update: "Taco Bell has reopened."

- Photos: The Flying Bombs of Nazi Germany

- The 22 Weirdest Military Weapons

- 10 of the Most Powerful Explosions Ever

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus