16 of the Most Interesting Ancient Board and Dice Games

Board and dice games have been a popular activity across almost all human societies for thousands of years — in fact, they are so ancient that it's unknown which game is the oldest or the original, if there is one.

Even the ancient Greeks played their share of board games; this illustration on a Greek amphora from the sixth century B.C. (now exhibited at the Vatican Museums in Rome) shows the Greek heroes Achilles and Ajax playing a dice game between battles at the siege of Troy.

Here's a look at some of the most interesting ancient board and dice games, ranging from several centuries to many thousands of years old.

Viking chess

In August 2018, archaeologists with the Book of Deer Project in Scotland unearthed a game board in what they think was a medieval monastery.

The researchers are looking for signs that the buried building was inhabited by monks who wrote the Book of Deer, a 10th-century illuminated manuscript of the Christian gospels in Latin that also contains the oldest surviving examples of Scottish Gaelic writing.

The ancient game board was scratched into a circular stone that was found above buried layers in the building dated to the seventh and eighth Centuries.

Historians think it was used to play hnefatafl, a Norse strategy game sometimes called Viking chess, although it is not actually related to chess. The game pits a king and 12 defenders in the center against 24 attackers arranged around the edges of the board.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Medieval Mill Game

In July 2018, archaeologists found a secret chamber at the bottom of a spiral staircase in Vyborg Castle, near Russia's border with Finland, which dates from the 13th century.

Among the objects found in the secret chamber was this game board, inscribed into the surface of a clay brick, that researchers think was used to play a medieval version of the board game known as "nine-man morris" or "mill."

The game dates back at least to the Roman Empire and was popular during the medieval period in Europe. To play, two players set up playing pieces on the intersections of the lines on the board and took turns to move. If a player built a "mill" of three pieces in a row, they were awarded with one of their opponent's pieces.

Lewis Chessmen

The game of chess itself has been played in Europe for many centuries — and the most famous chess set in archaeology may be the Lewis chessmen, which were found buried beside a beach on the island of Lewis in 1831.

It's not known just how they came to be there, but archaeologists think the game pieces were made in the 12th or 13th centuries, when Lewis was part of the Kingdom of Norway — and that they may have been buried for safekeeping by a traveling merchant.

The 93 playing pieces, thought to come from four complete chess sets, are carved from walrus tusks and whales' teeth. The largest pieces portray medieval kings, queens, churchmen (bishops), knights and warders (rooks), while the pawns are represented by carved standing stones.

Norwegian Knight

The game of chess is thought to have been introduced to Europe from the Middle East around the 10th century.

Several archaeological finds attest to the popularity of the game in medieval Europe, including this 800-year-old chess piece from Norway, which was found in 2017 during an excavation of a 13th-century house in the town of Tønsberg.

The piece is thought to represent a knight from the game of chess, which was known at the time by its Persian name shatranj. Archaeologists say it is carved from antler in an "Arabic" style, although they think it was probably made somewhere in Europe.

Game of Go

China's most famous board game is Go, which is now played around the world. It's thought to have been developed in China between 2,500 and 4,000 years ago, and may be one of the oldest games still played in its original form.

One story says the game was invented by the legendary Emperor Yao, said to rule from 2356 to 2255 B.C., to teach discipline to his son; another theory suggests that the game developed from a type of magical divination, with the black and white pieces representing the spiritual concepts of Yin and Yang.

Go was introduced to Japan in the eighth century A.D. and became the favorite game of aristocrats, who sponsored top players against other noble clans. Professional Go players in Japan today compete in tournaments for prizes worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Greek and Roman Dice

The Romans adopted dice games from the Greeks — collections like that of the British Museum contain many ancient dice from both regions and throughout the Roman Empire. A Roman-era "dice tower" for throwing dice was also found in Germany in 1985.

Ancient dice could be carved from stone, crystal, bone, antler or ivory, and while the cubical dice familiar today were common, they weren't the only shape that was used — several polyhedral dice have been found by archaeologists, including 20-sided dice engraved with Greek characters from Ptolemaic Egypt.

Archaeologists don't agree that such dice were always used for games — instead, they may have been used for divination, with the characters or words on each face of the die representing an ancient god who might assist the dice-thrower.

Chinese Dice Game

Dice were also used in ancient China — a mysterious game featuring an unusual 14-sided die was found in a 2,300-year-old tomb near Qingzhou City in 2015.

The die, made from animal tooth, was found with 21 rectangular game pieces with numbers painted on them, and a broken tile that was once part of a game board decorated with "two eyes … surrounded by cloud-and-thunder patterns.”

Archaeologists think the die, pieces and board were used to play an ancient board game named "bo" or "liubo" — but the game was last popular in China around 1,500 years ago, and today nobody knows the rules.

Israel Mancala Boards

In July 2018, archaeologists announced they had found a "games room" in their excavations of a Roman-era pottery workshop from the second century A.D. near the town of Gedera in central Israel.

Among the finds were several boards for the ancient game of mancala, consisting of rows of pits carved into stone benches, and a larger mancala game board carved into a separate stone.

The room seems to have served as a relaxation center for the pottery workers — a "spa" of 20 baths and a set of glass cups and bowls for drinking and eating were also found at the site.

Mancala is still a popular game today, especially in parts of Africa and Asia. It's played by moving counters, marbles or seeds among the pits of the game board, capturing an opponent's pieces, and moving pieces off the board to win the game.

India's Chaturanga

Chaturanga is the Indian forerunner of the Persian game shatranj, which became chess in the West. It was invented during the Gupta Empire of northern and eastern India around the sixth century A.D., although what may be "proto-chess" boards have been found in the Indus Valley region and dated to more than 3,000 years ago.

Chaturanga pieces included generals, elephants and chariots, which are thought to correspond to the modern chess pieces of queens, bishops and rooks.

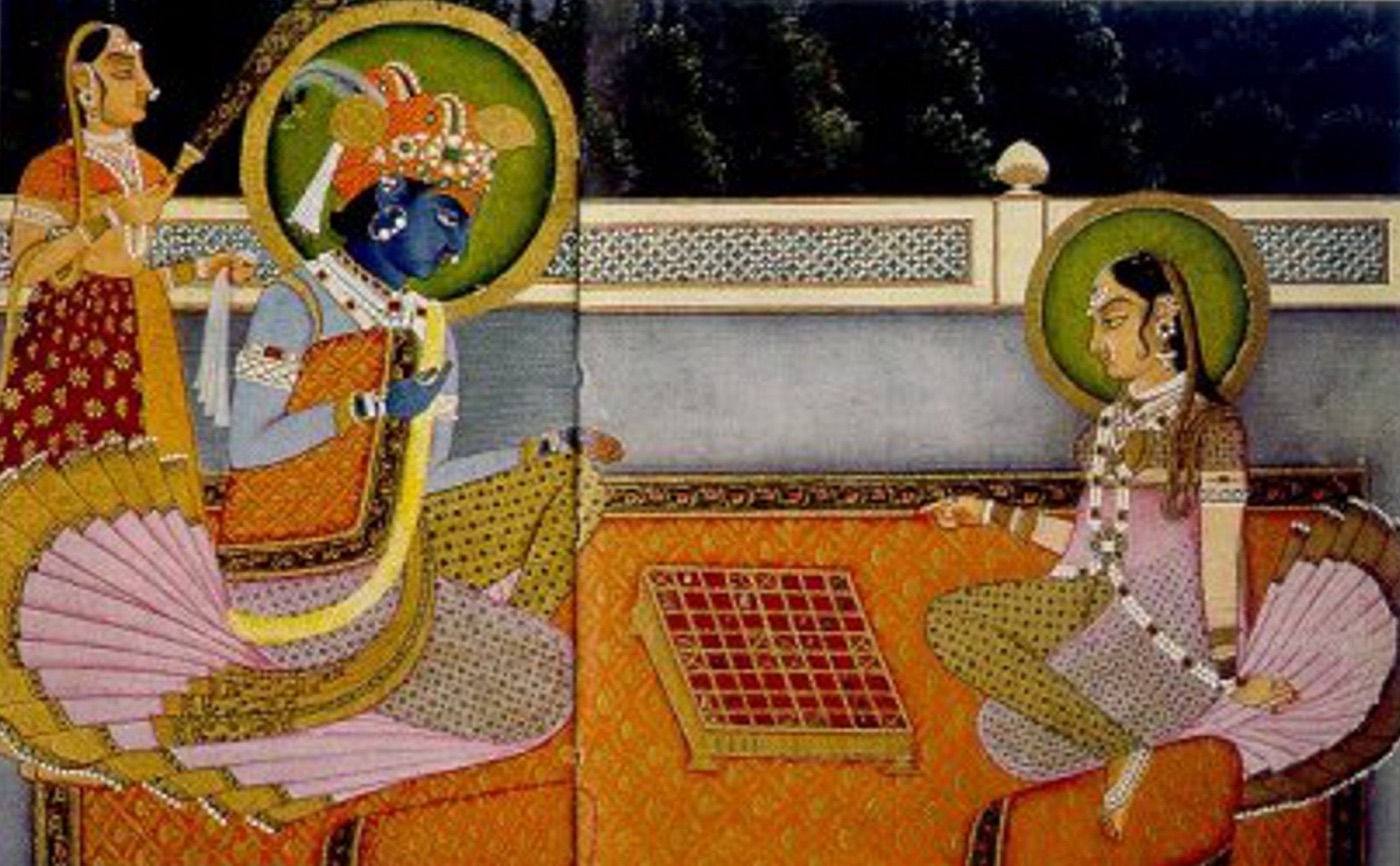

The name chaturanga comes from the ancient language of Sanskrit, meaning "four-armed" — a term used to describe the traditional divisions of an army. The image (shown here) from an Indian manuscript from the Gupta period, shows the Hindu gods Krishna and Radha playing Chaturanga on an 8-by-8 board of squares. The boards were not checkered like chess boards today, but they were marked in the corners and in the center squares — no one knows the reason.

Pachisi and Chaupar

The Indian game of pachisi is still played today, and a version of it is played in the West as the game of ludo. It's thought to have developed from earlier board games around the fourth century A.D., and is now considered India's national game.

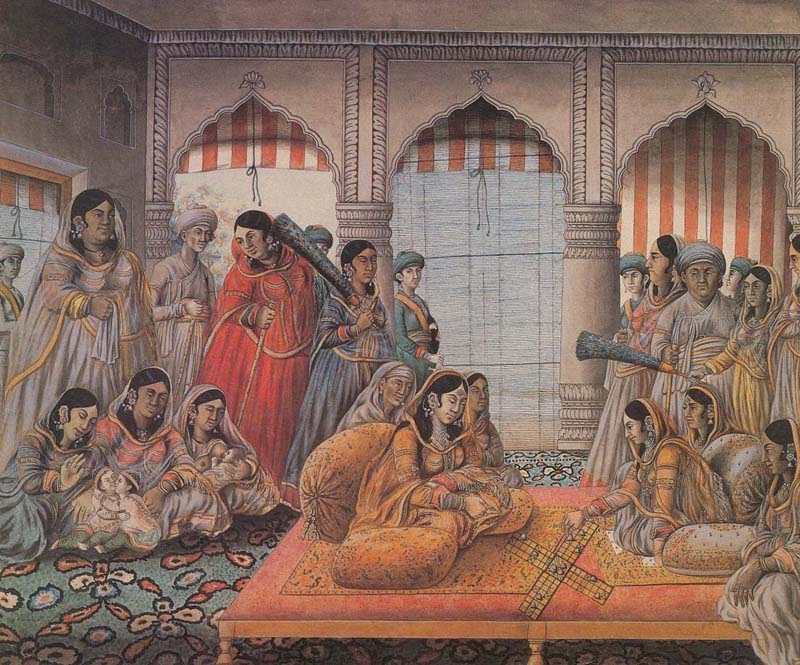

An illustration (shown) from an 18th Mughal painting shows the wives of the ruler of Lucknow playing chaupar, a game closely related to pachisi that uses the same cross-shaped board.

Traditionally, players in pachisi and chaupar moved their pieces around the board according to a throw of six or seven cowrie shells, which could fall with the opening upward or downward — dice are often used today.

Gyan Chaupar

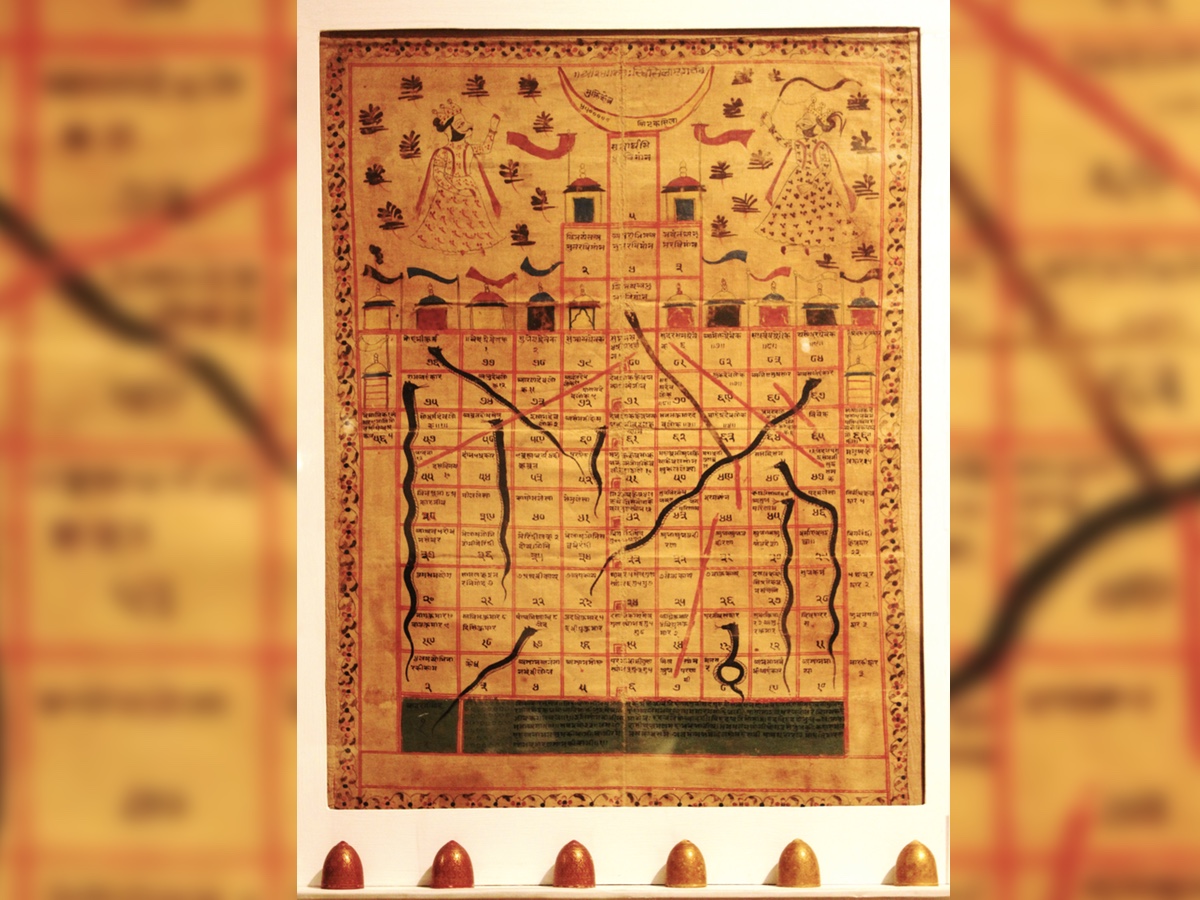

The Indian game of gyan chaupar is the original "snakes and ladders" — versions of it date from the 10th century A.D.

It was supposed to teach morality, with players moving from the lower levels of spiritual bondage to the higher, heavenly levels of enlightenment to win the game.

During the British rule of India, the game was introduced to the West along with other games that had similar moral meanings; eventually, versions of the game were produced without the moral messaging.

A gyan chaupar board and game pieces from the 18th century was on show in the National Museum of India in 2018 (shown).

Mesoamerican Patole

Versions of the game patole or patolli were played throughout pre-Columbian America by several different cultures at different times, including the ancient Toltecs and Mayans.

This illustration from an Aztec codex of the 16th century shows Macuilxōchitl — the god of art, beauty, dance, flowers and games — watching a game of patole being played. The Spanish conquistadors apparently reported that the last Aztec king Montezuma enjoyed watching the game being played at his court.

Patole players would bet items of great value on the outcomes of their games — the idea was to use throws of beans or dice to move all their game pieces around the cross-shaped board and into specially marked squares to win.

The shape of the board has led some anthropologists to speculate that the Mesoamerican game is related to the Indian game of pachisi, which would imply some sort of pre-Columbian contact between the two regions. But other researchers have dismissed any such likeness.

Hounds and Jackals

Boards and pieces for the game now known as "hounds and jackals" have been found at several ancient Egyptian archeological sites, with the earliest examples dating from around 2000 B.C.

American archaeologist Walter Crist has also found a version of the same game cut into the rocks of a Bronze Age shelter in Azerbaijan.

This photograph shows a game set from the 18th century B.C., found in the tomb of the pharaoh Amenemhat IV in Thebes by the British archaeologist Howard Carter in 1910. The game can now be seen at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The game board has two sets of 29 holes, and each player has 10 sticks that fit in the holes, decorated with either dog heads or jackal heads. The aim of the game is thought to have been to move a player's pieces from one end of the board to another, while capturing an opponent's pieces on the way.

Egyptian Senet

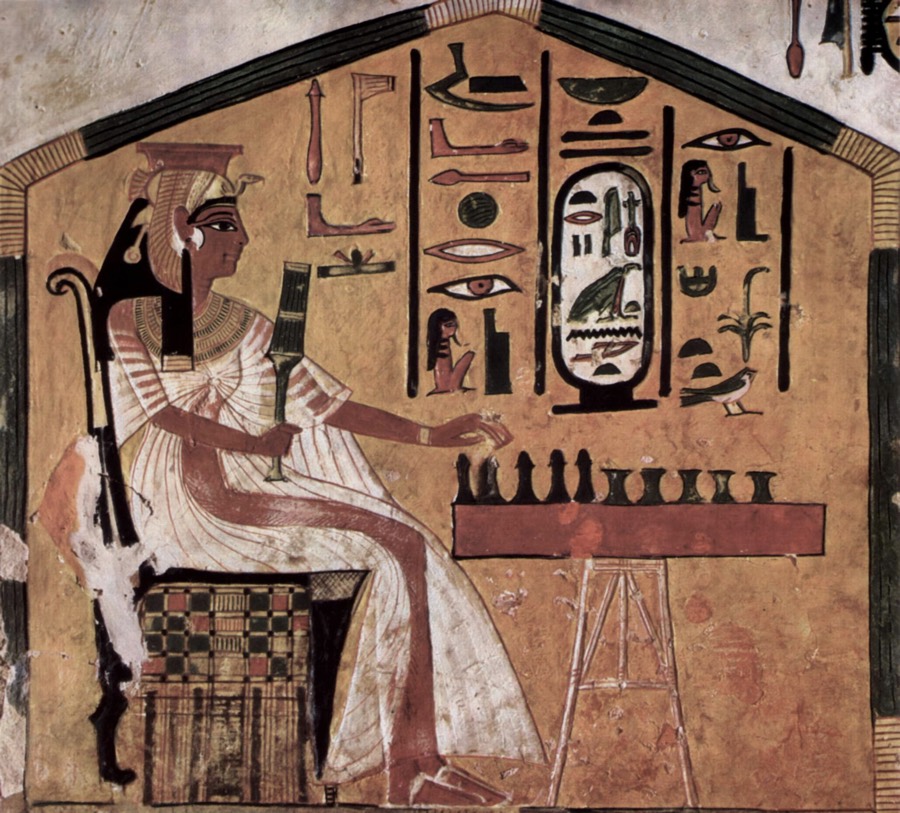

The ancient Egyptian game of senet is one of the world's oldest board games — pieces of boards thought to have been used for senet have been found in tombs of Egypt's First Dynasty of kings, dating to earlier than 3000 B.C.

A painting (shown) on the wall of the 12th century B.C. tomb of the Egyptian queen Nefertari shows her seated at a table playing the game, which can be recognized by the shape of the pieces.

Senet game sets have also been found at other ancient sites in the Middle East, probably as a result of trade with Egypt.

Although the original rules of senet are not known, some modern reconstructions are based on ancient writings about the game. It's thought the aim was to move a player's pieces according to the numbers given by "throw sticks" — a type of dice — while avoiding certain unlucky squares, represented by symbols on the game board.

Egyptian Mehen

The word mehen, meaning "the coiled one," was both the name of an ancient Egyptian snake-god and of a board game played by Egyptians before the Old Kingdom period, before 2150 B.C.

The relationship between the god and the game is unclear, but the game of mehen was very popular and appears on tomb paintings from the time.

The coiled game boards have been found with six carved game pieces shaped like lions, and with six sets of small balls or marbles that may have been the "prey" of the lion pieces. The ancient rules of the game are unknown, although there are several modern reconstructions.

Royal Game of Ur

A single board for what's now known as the Royal Game of Ur was unearthed early in the 20th century during excavations of a Sumerian tomb in the Royal Cemetery of Ur, in modern-day Iraq — which means it dates from at least 3100 B.C. Other game boards have since been found in North Africa, the Middle East and Asia.

Unusually, at least one version of the ancient rules is well known because they were preserved on a Babylonian clay tablet written by a scribe in the second century A.D.

The object of the game was to move all of a player's pieces along the board before an opponent could do so. Four-sided pyramid-shaped dice were used to determine how the pieces could move in the game.

The ancient game is now being revived as a community pastime at the University of Raparin, in the Kurdistan region of Iraq.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus