Scientists Are '99 Percent' Sure There's a Huge Exoplanet Very Close to Our Solar System

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

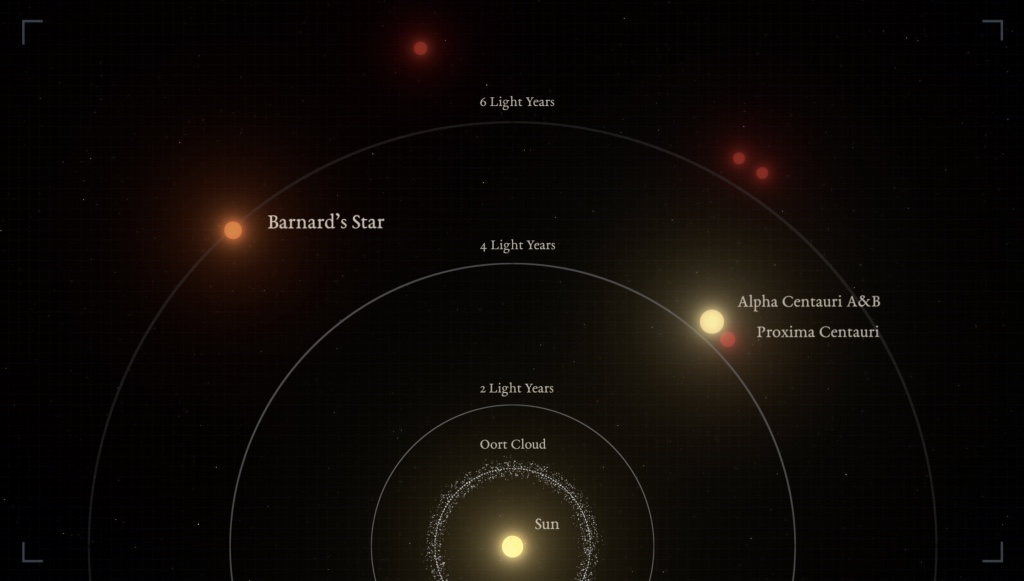

Sitting about 6 light-years away from our sun, the red dwarf named Barnard's star is the nearest solitary star to our solar system and the fastest-moving star in our night sky. It's also really wobbly.

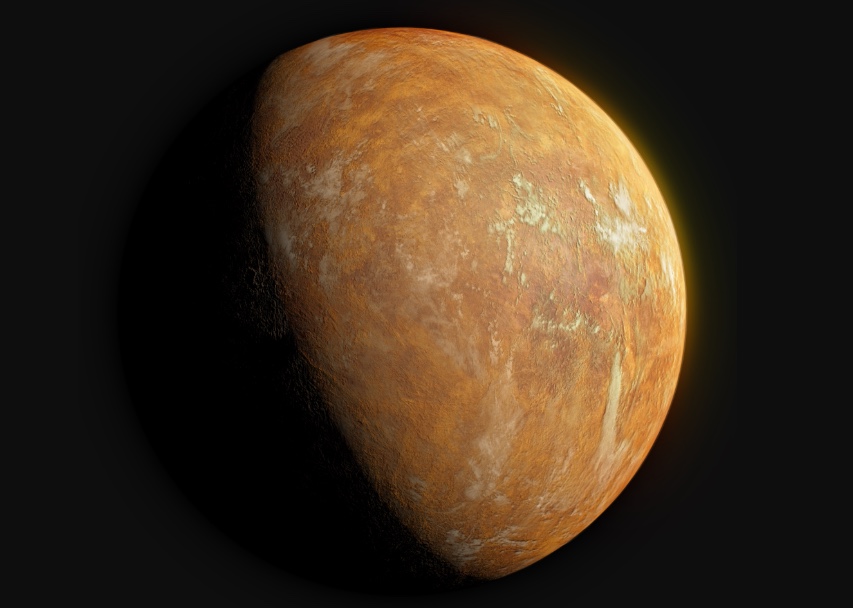

Chalk up the wobbles to old age if you like: The star may have been born some 10 billion years ago — making it more than twice the age of our sun — and it has only 16 percent of the sun's mass. But astronomers prefer a different explanation. A new paper published today (Nov. 14) in the journal Nature combines 20 years of research to conclude "with 99 percent confidence" that Barnard's star is being tugged about its orbit by a nearby exoplanet — a world that's roughly three times the size of Earth and loaded with ice.

Astronomers caught wind of this possible super-Earth (that is, an exoplanet that has a mass greater than Earth's but less than the ice giants, Uranus and Neptune) nearly 20 years ago while taking velocity measurements of Barnard's star. The scientists saw that, every 230 days or so, Barnard's star seemed to wobble its way closer to our solar system before slowly retreating again. The presence of a large planet, which could exert its own gravitational influence on Barnard's star as it orbits around its host, was a possible explanation. Still, more data was needed to say for certain. [9 Most Intriguing Earth-Like Planets]

Now, following 20 years of observations from telescopes around the world, the data is there. In a new study, an international team of scientists looked at more than 700 velocity measurements of Barnard's star and determined that the likeliest explanation for the star's wobbly behavior is the influence of a nearby planet orbiting its local sun every 233 days.

"We used observations from seven different instruments, spanning 20 years, making this one of the largest and most extensive datasets ever used for precise radial velocity studies," study author Ignasi Ribas, of Spain's Institut de Ciències de l'Espai, said in a statement. "We are over 99 percent confident that the planet is there."

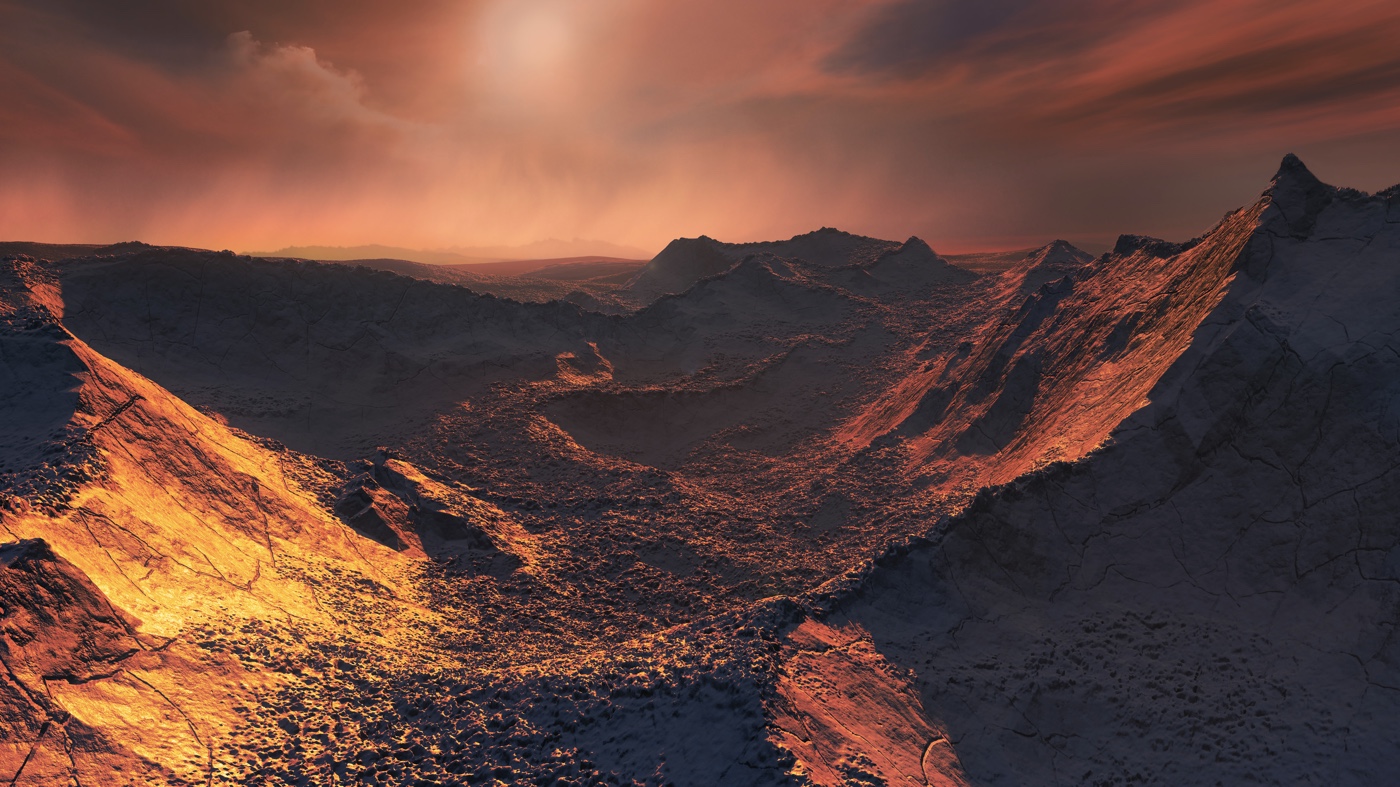

This probable new planet — which the astronomers have dubbed Barnard's star b — likely sits about as far away from its host star as Mercury does from our sun. That puts the planet near the small star's "snow line," or the celestial border beyond which any planetary water would be frozen. Scientists have previously suggested that the snow line is a prime place for planet formation, as frozen matter can easily glom onto other bits of gas and debris swirling around the nearby star.

Unfortunately, that also puts Barnard's star b in a precarious position for hosting life. The planet is close enough to its host star that it likely does not have an atmosphere, and far enough from it that surface temperatures likely dip to about minus 240 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 150 degrees Celsius). That means any water is likely to be permanently frozen, the researchers wrote.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While this might prevent Barnard's star b from being a candidate for extraterrestrial life, the nearby super-Earth is still a prime subject for honing scientists' exoplanet discovery and monitoring techniques. Future telescope missions might be able to image the neighboring world directly.

According to study co-author Cristina Rodríguez-López, researcher at the Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía, this discovery represents "a boost to continue on searching for exoplanets around our closest stellar neighbors, in the hope that eventually we will come upon one that has the right conditions to host life."

- 7 Everyday Things That Happen Strangely in Space

- Interstellar Space Travel: 7 Futuristic Spacecraft to Explore the Cosmos

- Photos: The 8 Coldest Places on Earth

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus