The Oldest DNA from Giant Pandas Was Just Discovered in a Cave in China

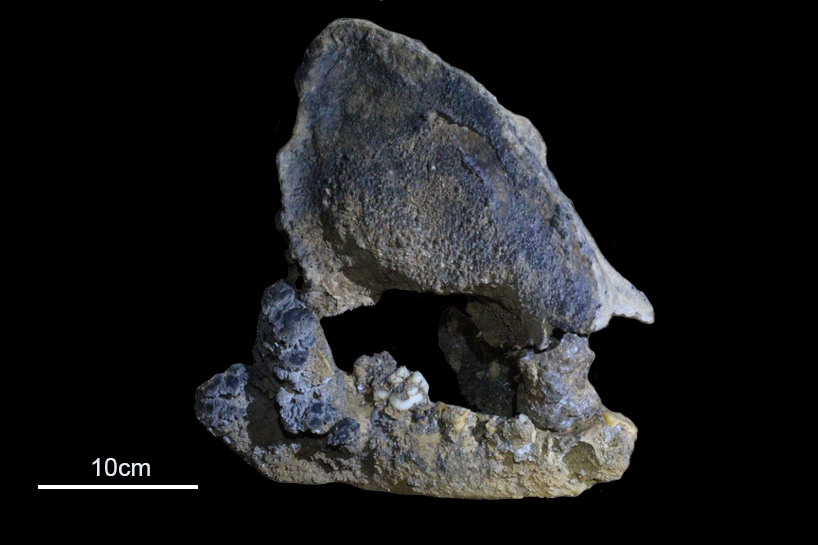

Scientists in China found a fossil from a giant panda that lived 22,000 years ago. Until they excavated the fossil, reassembled it and analyzed its mitochondrial DNA, biologists had no idea this panda lineage even existed.

It's now considered the oldest DNA from giant pandas to date, the researchers said.

The panda fossil turned up in Cizhutuo Cave in the Guangxi region of China. No pandas live there today, the researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences wrote in a paper published today (June 18) in the journal Current Biology. An unexpected giant-panda fossil find was exciting, they wrote, because researchers don't have a good sense of the history of the 2,500 giant pandas alive in the world today. Researchers know that 20 million years ago, the current batch of living giant pandas split from all other bears. They don't know much about their lineage since.

This fossil, the researchers showed, came from a creature that separated from living giant pandas much more recently: about 183,000 years ago. [In Photos: The Life of a Giant Panda]

Before the researchers could determine that timeline, though (and, in fact, before they were certain the fossil came from a distinct species), the researchers had to reassemble the tiny fragments of mitochondrial DNA that remained after millenia in a subtropical cave. (Mitochondrial DNA is distinct from the DNA found in the nucleus of a cell but can offer similar information about a creature's ancestry.)

To pull that off, researchers fit 148,329 fragments of DNA together like puzzle pieces, using a living giant panda's mitochondrial DNA as a guide. All of the fragments came from one individual, and all together, the researchers were able to use them to parse the animal's ancestry.

The DNA also had dozens of mutations that would have changed how the animal developed, the researchers said. They suggested those mutations may have been adaptations to survive in the cooler climate of the subtropics during the ice age 22,000 years ago.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus