Scientists Figured Out How to Make Ceramics That Bend and Mush Instead of Shattering

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A team of scientists has figured out how to make ceramics that bend and mush instead of shattering (though under enough pressure they will still crack).

That's a potentially lifesaving discovery: Heat-resistant ceramics are critical materials in machines that run hot, and they also coat the metal parts inside airplane engines. But ceramics are also dangerous materials to work with, due to their tendency to shatter without warning. And sudden shattering is bad news when the ceramic is the only thing keeping, say, a jet engine from melting. A ceramic material that bends and mushes under pressure before completely shattering should survive longer, revealing visible signs that it's going to break long before actually shattering.

To build a more flexible ceramic, the researchers, from Purdue University, messed with the "sintering" process, which is the method of firing a ceramic with extreme heat in order to give it its chemical structure, shape and toughness. [Flying Saucers to Mind Control: 22 Declassified Military & CIA Secrets ]

Flexible materials, like metals, are able tocan bend before breaking because they have useful "defects." Those are places in their chemical structure where molecules are misaligned and can slide around each otherone another. Ceramics typically don't have those kinds of defects.

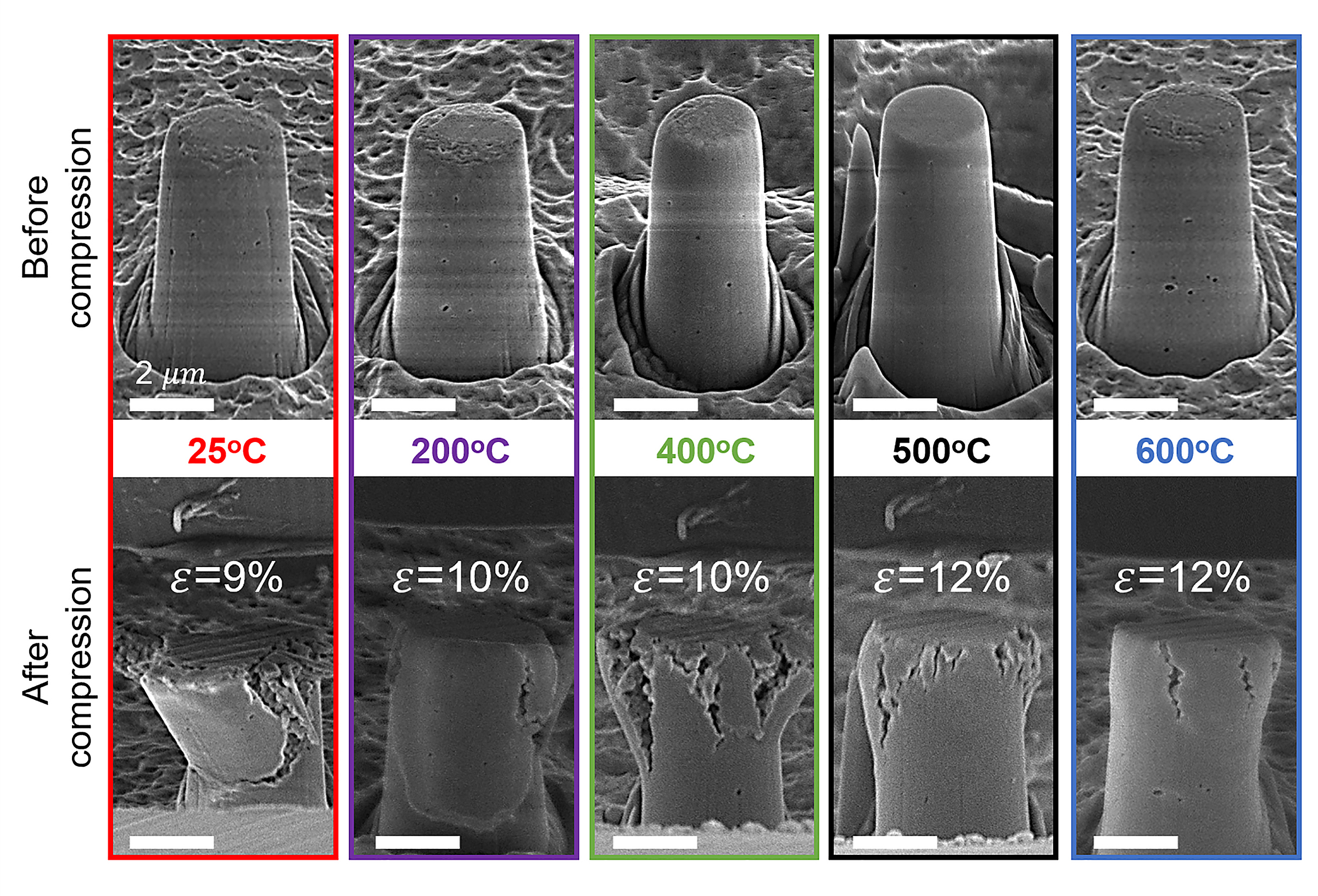

But by flash-sintering a heat-resistant ceramic called yttria-stabilized zirconia, or sintering it while applying an electric field, the researchers could introduce those sorts of defects. When they tested little columns of the stuff under pressure, they found that the flash-sintered version was three to four times slower to shatter than normal yttria-stabilized zirconia (though it was still just half as shatter-resistant as metal).

"In the past, when we applied a high load at lower temperatures, a large number of ceramics would fail catastrophically without warning," Xinghang Zhang, a professor of materials engineering at Purdue and a co-author of the study, said in a statement. "Now, we can see the cracks coming, but the material stays together; this is predictable failure and much safer for the usage of ceramics."

That doesn't mean researchers are ready to slap the stuff onto airplane engines, but it does mean materials scientists will be rushing to investigate further.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus