Biomed CEO Injects Himself with DIY Herpes Vaccine — Why That's Not a Good Idea

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

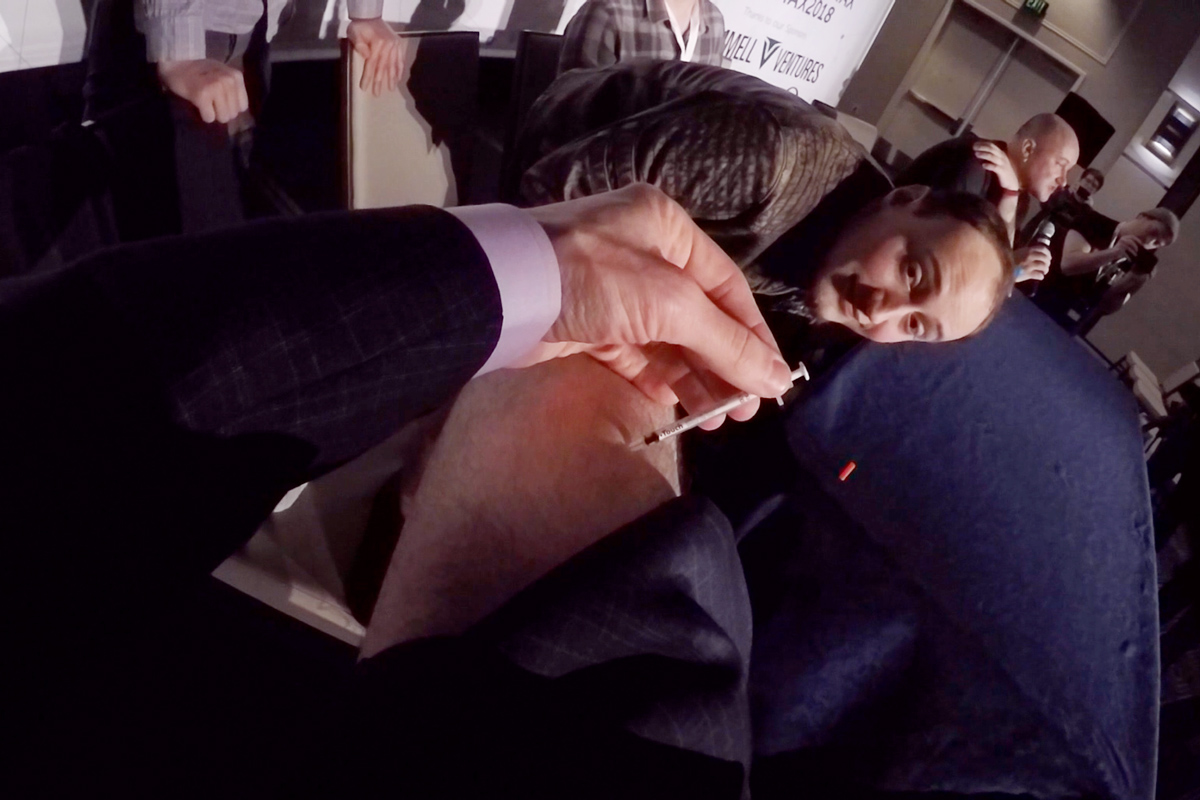

On Sunday (Feb. 4), biomedical startup CEO Aaron Traywick injected himself with an untested herpes treatment in front of a live audience.

And — because it's 2018 — Traywick streamed the whole thing on Facebook, of course.

Traywick touted the self-experimentation to BuzzFeed as an attempt to increase scientific transparency and move science forward, but biomedical experts say that acting as a human guinea pig does nothing of the sort. A single-subject experiment can't show that a treatment works, and it certainly can't prove it safe, said Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious-disease specialist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, who noted that he couldn't comment on Traywick's experiment specifically.

"Medical science is littered, as they say, with individual experiments and small case series that initially looked very optimistic, but subsequently turned out to be not valid," Schaffner told Live Science. [10 'Barbaric' Medical Treatments That Are Still Used Today]

Self-experimentation

Traywick is the CEO of Ascendance Biomedical, a small startup that last year staged a live demonstration of a purported gene-therapy treatment for HIV. Gene therapies are treatments that aim to alter an individual's DNA to produce the treatment inside the person's own cells. Instead of producing and injecting a therapeutic protein, for example, the idea is to alter a person's genome so that it will produce that protein itself, presumably for the long haul.

The volunteer test subject in the HIV experiment, a biohacker named Tristan Roberts who has HIV, reported one month after the injection that his viral load had risen, not fallen, after the test. His count o a particular infection-fighting cell known as CD4 cells had risen slightly, but — illustrating the difficulties of gleaning useful information from one-man experiments — that could have been because he had a slight fever that week, Roberts wrote on Medium.

Not long after Roberts' livestreamed injection of the do-it-yourself HIV therapy, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning against using untested gene therapies. Clinical studies of these therapies, like any new medication or vaccine, require an investigational new drug application, according to the agency's warning. The sale or human testing of any therapy without this application is illegal.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Traywick and Roberts, however, got around this requirement by self-experimentation, which the FDA has so far not prosecuted. (The company's promise to give away its experimental compounds to anyone who wants them might fall more afoul of the law, Patti Zettler, a former FDA associate chief counsel, told BuzzFeed News.)

In Traywick's demonstration before a live audience at the BdyHax conference in Austin, Texas, on Sunday, he compared himself to Jonas Salk, inventor of the polio vaccine, and Louis Pasteur, who developed the rabies vaccine.

Shortcuts

Pasteur, who worked in the late 1800s before modern medical ethics took hold, did use an experimental rabies vaccine on a boy who had been bitten by a rabid dog, though only after the vaccine had been tested on animals and only after great hesitation about the risk, according to "Who Goes First? The Story of Self-Experimentation in Medicine" (University of California Press, 1998). Finally, Pasteur agreed to give the vaccine, given that there was no other treatment and that the boy was likely to die within days without it.

(The boy survived. Pasteur went on to conduct human trials of the vaccine, which was effective but caused fatal reactions in several participants in his studies. According to "Who Goes First," he was criticized for much of the rest of his life for moving into human testing too quickly.)

Salk consented to have the polio vaccine tested on himself and his family before field trials in the 1950s, according to a 2012 paper in the Texas Heart Institute Journal, but the vaccine had already undergone animal testing. The treatment Traywick injected had not been tested in animals.

"The fact that somebody is standing on stage injecting themselves with something already makes me worried," said Dr. Paul Offit, a vaccine expert at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, who helped invent the rotovirus vaccine. The rotovirus vaccine took 26 years to develop, Offit said: 10 years for basic research, and another 16 to develop a safe and effective version of the vaccine for humans.

"If you want something to be a product, you have to show every step of the way that you have followed good practices," Offit told Live Science.

"Good practices" for a new therapy or vaccine means preclinical work (which includes animal experimentation) and must be documented for the FDA to grant that coveted investigational new drug license. Then, Schaffner said, the developer can move into Phase I clinical trials on small groups of people, which are primarily designed to make sure the new drug is safe. Next come Phase II trials, which examine both effectiveness and safety.

Finally, Phase III trials use gold-standard methods to show that a drug really works and how well: They are large-scale and double-blind, Schaffner said, so that neither the patient nor the researchers know who is getting the real treatment versus a placebo. Throughout the process, an independent panel of experts known as a "data and safety monitoring committee" reviews the research to ensure that the experiments are being done correctly and safely, Schaffner said. Schaffner currently serves on two such committees. [11 Surprising Facts About Placebos]

It's unclear how the FDA will react to Ascendance's hacker mentality, though "they [the FDA] don't like showmanship," Offit said. But the real danger to companies like Ascendance may be the inherent risk of what they're doing. In 1999, a teenager named Jesse Gelsinger joined a clinical trial of a gene therapy meant to cure his genetic liver disease. The therapy instead triggered a major immune response that killed Gelsinger within days.

In any new drug treatment, there will be side effects and adverse events, Schaffner said. Gene therapy, which is scientifically and clinically new, is unlikely to be an exception.

"This is an area where you want to be doubly cautious, because we haven't moved into this area before," he said.

The FDA approved its first gene therapies only last year.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus