Brain Scans Can Reveal Who Your True Friends Are

A new study finds that close friends react to spontaneous stimuli, such as TV channels flicking by, with remarkably similar thought processes. Researchers also found that they could accurately predict how close two people were based solely on their brain activity in response to a series of unfamiliar video clips.

"Neural responses to [stimuli such as] videos can give us a window into people's unconstrained, spontaneous thought processes as they unfold," lead study author Carolyn Parkinson, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles, said in a statement. "Our results suggest that friends process the world around them in exceptionally similar ways." [7 Ways Friendships Are Key To Your Health]

Simply put: You and your besties really do think alike.

Social magnetism

There are numerous reasons why two strangers might become friends, and many of these reasons rely on similarities. According to the study, which was published yesterday (Jan. 30) in the journal Nature Communications, a disproportionate number of friendships form between individuals who share similar ages, genders, ethnicities and other demographic factors. Recent research even suggested that you're more likely to choose friends who have DNA sequences similar to yours. With all this in mind, is it possible that you also might choose friends who have similar thought processes?

To test that hypothesis, the researchers recruited an entire first-year graduate-school class of 279 students to take an online survey about their social ties to one another. Each student was provided a list of every other student and was asked to indicate which classmates they had socialized with outside of class in the four months since school began.

The survey results allowed the researchers to map the graduate class's complete social network, indicating which classmates were friends, which were friends of friends, and so on. (Interestingly, the researchers found a maximum of six degrees of separation between any two students.)

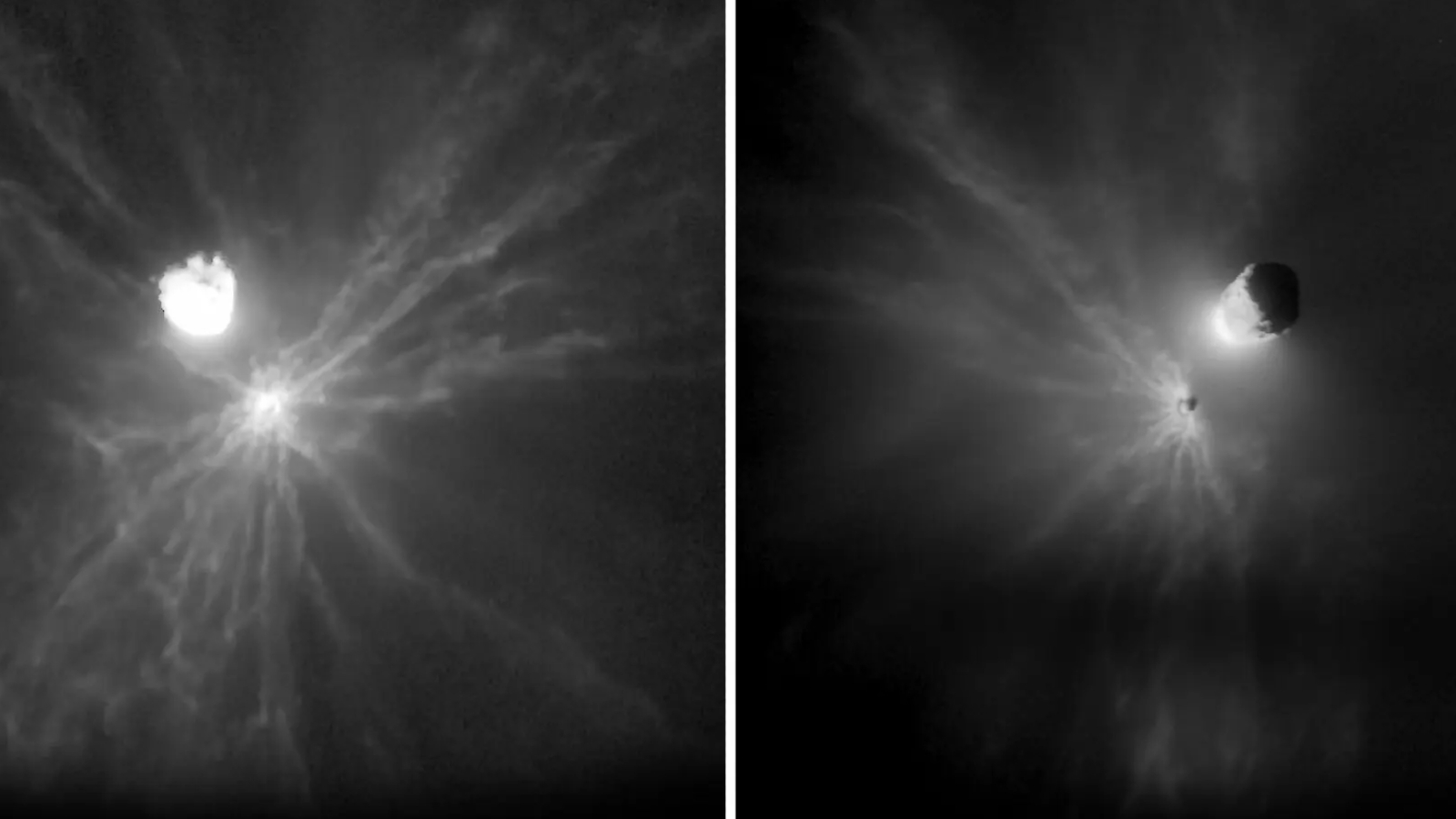

Forty-two of these students were subsequently recruited to take part in a functional MRI (fMRI) experiment. Researchers monitored the participants' brain activity while they watched a series of 14 unfamiliar video clips, each ranging from about 90 seconds to 5 minutes — the equivalent of "watching television while someone else channel surfed," the researchers wrote. The clips represented a spectrum of genres and emotions, and included scenes from a soccer match, an astronaut's view of Earth, the political show "Crossfire" and a documentary about baby sloths.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the researchers compared the students' brain activity, they found that close friends showed remarkably similar reactions in brain regions associated with emotion, attention and high-level reasoning. Even when the researchers controlled for other similarities — including the participants' age, gender, and ethnicity — friendship still proved a reliable indicator of comparable neural activity. The team also found that differences between the fMRI responses could be used to reliably predict the social distance between any two participants.

"We are a social species and live our lives connected to everybody else," senior study author Thalia Wheatley, an associate professor of psychological and brain sciences at Dartmouth, said in a statement. "If we want to understand how the human brain works, then we need to understand how brains work in combination — how minds shape each other."

To that point, a question still remains: Does having friends physically change the way you think, or do you instinctively choose your friends so you don't have to change? Researchers don't know the answer yet — but until they do, there's plenty of channel surfing to be done.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.