5,500-Year-Old Wooden Clubs Were Deadly Weapons

How do you solve a Stone Age murder mystery? First, identify the weapon.

Archaeologists in the United Kingdom are turning to forensic methods to understand violence in the Neolithic period.

In experiments described in the journal Antiquity yesterday (Dec. 7), researchers used a replica of a 5,500-year-old wooden club to see what kind of damage they could inflict on a model of a human head. They found that such clubs were indeed lethal weapons. [7 Bizarre Ancient Cultures That History Forgot]

Stone Age conflict

Archaeologists have found ample evidence of violence in Western and Central Europe during the Neolithic period, through burials of people who had skull fractures—some healed, some were fatal —from an intentional blow to the head. But it was often unclear where these injuries came from.

"No one was trying to identify why there was blunt-force trauma in the period," said study leader Meaghan Dyer, a doctoral student at the University of Edinburgh. "We realized we needed to start looking at weapons."

Later periods like theBronze Agebrought metal weapons such as swords and daggers. But Neolithic people didn't leave behind many objects that could be categorized definitively as weapons for violence against human beings, Dyer said. A bow and arrow, for example, could be used for hunting, but it can also be used to shoot another person. [Photos: Gilded Bronze Age Weaponry from Scotland]

"We wanted to see if we could come up with a really efficient method to determine which tools could be used as weapons," Dyer said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

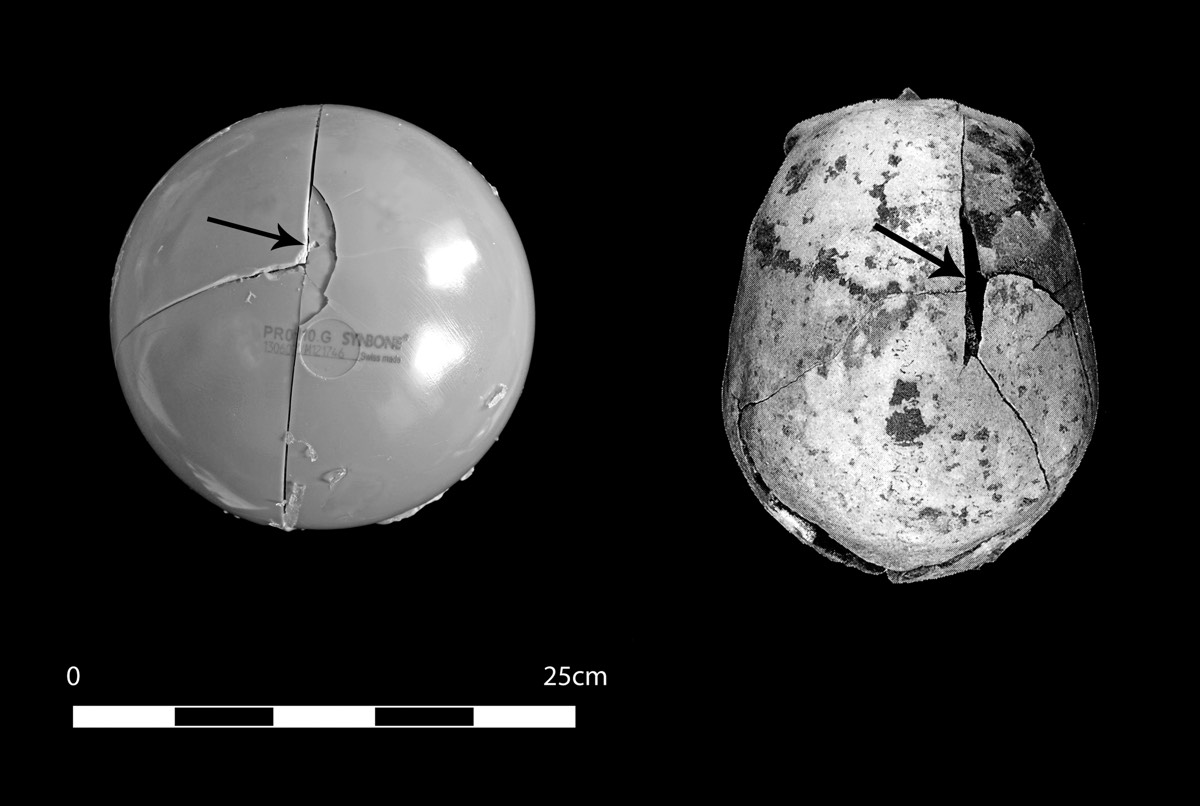

So, Dyer and her supervisor Linda Fibigerturned to synthetic skull models that are designed for ballistics tests for guns. (Animal models and human cadavers were not scientifically or ethically acceptable.) These skulls consisted of a rubber skinwrapped around a polyurethane, bone-like shell that was filled with gelatin to simulate the brain.

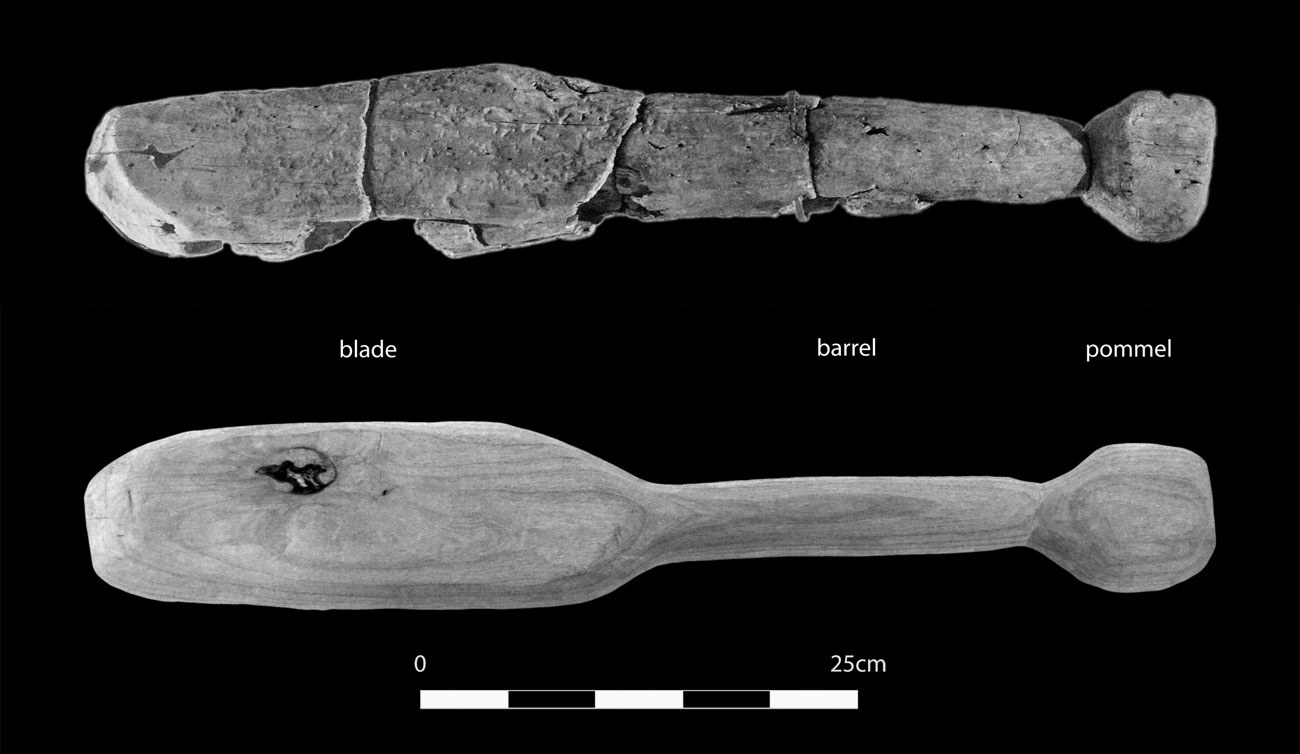

Dyer wanted to see how these artificial human heads would hold up after getting bashed by a replica of a Neolithic wooden club found known as the Thames beater.

Murder weapon?

"Wooden clubs were still used as weapons in the following Bronze Age, so it is quite likely that they were an important piece of Neolithic weaponry," said Christian Meyer, head of the Osteo-Archaeological Research Center in Goslar, Germany, and has studied Neolithic violence but wasn't involved in the study.

Wood typically does not preserve well in the archaeological record, but the Thames beater was pulled out of the waterlogged soil on the north bank of the Thames River in theChelseaarea of London. It has been carbon dated to 3530-3340 B.C. and is now housed in the Museum of London. Dyer described the club as a "very badly made cricket bat" that's much heavier at the tip.

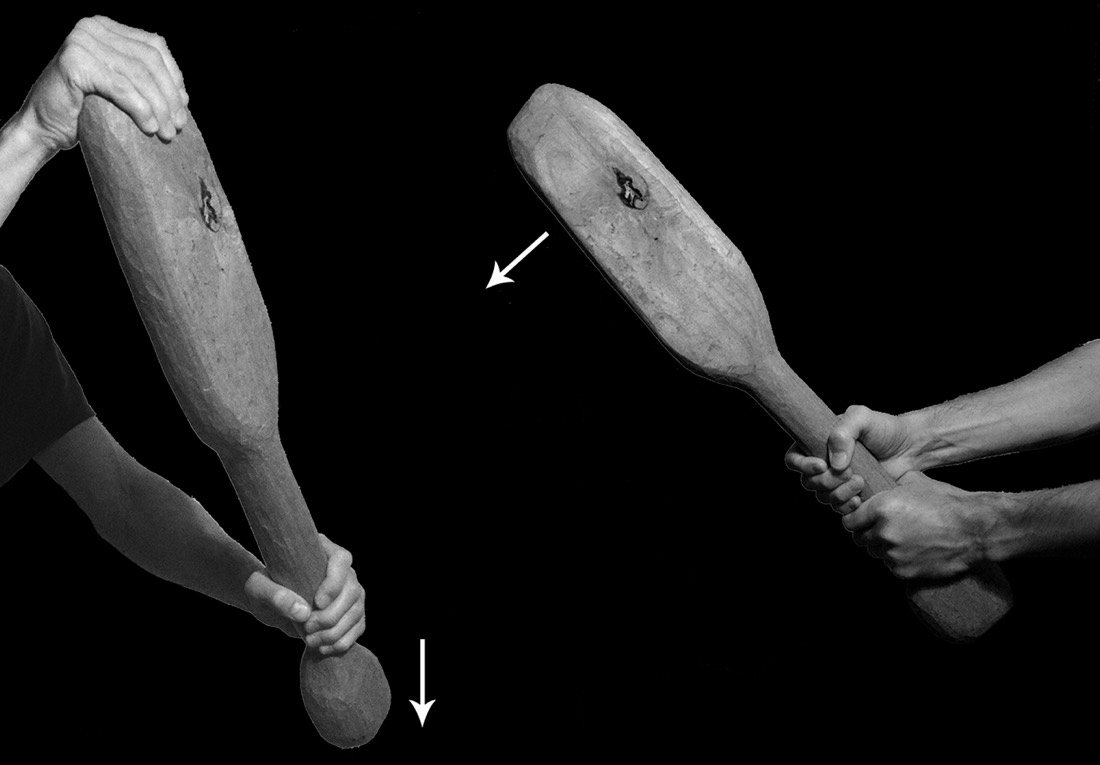

Dyer enlisted a friend, a 30-year-old man in good health, to do the bashing, and told him to swing as hard as he could at the "skulls," as if he were in a battle for his life. The resulting fractures resembled injuries seen in the real Neolithic skulls. One fracture pattern closely matched a skull from the 5200 B.C. massacre site of Asparn/Schletz in Austria, where archaeologists had previously speculated that wooden clubs might have been used as weapons.

"We didn't go out aiming to replicate a particular injury, and when we got that fracture pattern, we were quite excited," Dyer said. "We knew right away that we had a match there."

Reconstructing raids and assaults

If archaeologists can link specific weapons to specific injuries, then they can start to reconstruct scenes of violence in the Neolithic era. The Thames beater, for instance, "very clearly is lethal," Dyer said. It would probably be used only in scenarios where you were trying to kill your opponent. Dyer and her colleagues are starting to look at scenarios where different weapons might have left non-fatal head wounds.

"Violence is more complex than maybe we've understood to this point," Dyer said. "I'm of the opinion that maybe the word 'war' doesn't apply yet in this period because societies were a bit smaller. But we can start to understand things like raiding, assault, infanticide and murder. By understanding that, we can much better understand what it meant to be a human being in a Neolithic society in Europe."

Meyer said that the experimental setup "is a good starting point for further in-depth research into the question of what weapons were used in the Neolithic and on whom."

Rick Schulting, an archaeologist at the University of Oxford, who was not involved in the study, added that the findings "are relevant to any period in which wooden clubs are used as weapons to inflict harm." The researchers had also found that direct blows can result in linear fractures, and previously, such fractures had usually been attributed to falls, Schultingsaid. He added that this finding "may lead us to revisit some cases that were previously discounted as evidence of violence."

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus