Solar Eclipse Damage to Woman's Eye Revealed in Striking Images

Using a new type of imaging, doctors were able to peer into the eyes of a young woman and see — on the cellular level — the type of damage that occurs from looking directly at the sun during an eclipse.

The woman, who is in her 20s, damaged her eyes during the total solar eclipse on Aug. 21, according to a new report of her case, published today (Dec. 7) in the journal JAMA Ophthalmology.

In the woman's case, she told doctors that during the eclipse, she looked at the sun for approximately 6 seconds several different times without protective eyewear, and then again for 15 to 20 seconds with a pair of eclipse glasses, according to the case report. She also said she viewed the solar eclipse with both eyes open. [Did the Solar Eclipse Damage Your Eyes? Here's How to Tell]

But the woman was not in the path of totality during the eclipse (during totality it is safe to look at the sun without eye protection), and the sun was only 70 percent obscured during the peak of the eclipse in the area that the woman viewed the event. That meant the sun's bright light was still visible and damaging to the eyes.

Four hours after watching the eclipse, the woman said she had blurred vision, a type of distorted vision called metamorphopsia, and color distortion. The symptoms were worse in her left eye, in which she also reported seeing a central black spot, according to the report.

However, it wasn't until three days later that she went to the doctor, who found that she had a condition called solar retinopathy — a rare form of retinal injury that results from direct sungazing, the report said.

Looking into the eyes

Because total solar eclipses are rare, doctors don't often see patients with solar retinopathy, and when they have in the past, they didn't have the same imaging tools available to use.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We have never seen the cellular damage from an eclipse because this event rarely happens and we haven't had this type of advanced technology to examine solar retinopathy until recently," lead author Dr. Avnish Deobhakta, an assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, said in a statement.

The new technology, called adaptive optics, allows doctors and researchers "to get an exact look at this retinal damage on such a precise level [which] will help clinicians better understand the condition."

Solar retinopathy occurs when bright light from the sun damages the retina, causing blurry vision or a blind spot in one or both eyes. However, the damage is often painless and a person generally will not experience these symptoms immediately after looking directly at the intense light of the sun.

After examining the woman, the doctors determined she had burned holes in both of her retinas. She also had photochemical burns in her eyes, according to the report.

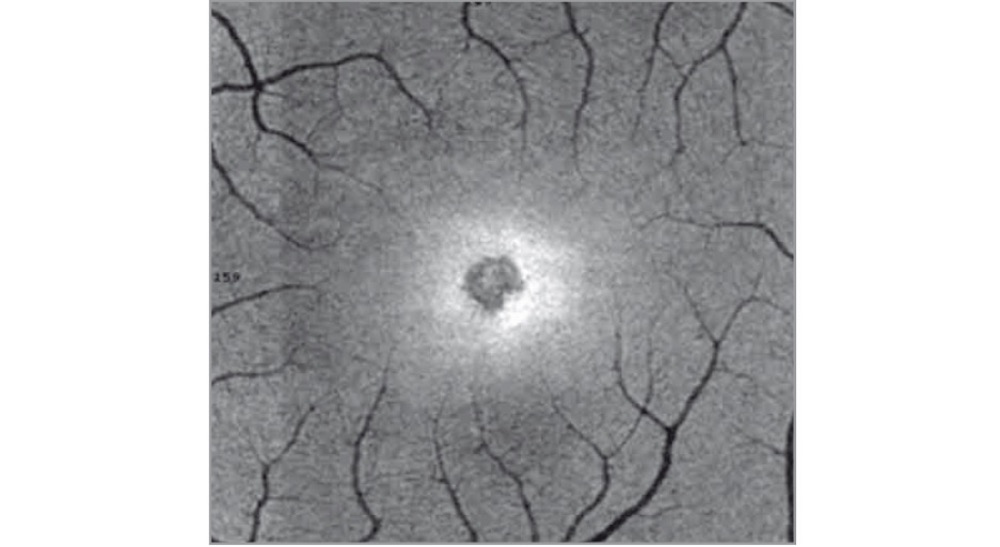

Adaptive optics allows doctors to examine the microscopic structures of a patient's eye with extreme detail in real time, the report said. Using the technique, the researchers obtained high-resolution images of the damaged photoreceptors in the woman's eyes. (Photoreceptors are the light-sensitive rods and cones of the eye's retina.)

The images showed no significant vision damage to the right eye, but revealed a yellow-white spot in the left eye. The images also showed multiple areas of decreased sensitivity and a central scotoma, or blind spot, in the left eye, according to the report.

The researchers said in the statement they hope the images will help provide a better understanding of solar retinopathy, which currently cannot be treated.

In addition, the report "can prepare doctors and patients for the next eclipse in 2024, and make them more informed of the risks of directly viewing the sun without protective eyewear," lead author Dr. Chris Wu, a resident physician at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai, said in the statement.

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus