Smallpox-Related Viruses Are Still a Threat to Humans, Experts Warn

Smallpox has been eradicated for decades, but other, related "poxviruses" are still around and continue to pose a risk to humans, experts say.

In fact, cases of human infection with viruses in the same family as the smallpox virus are appearing in growing numbers.

What's more, in recent years, researchers have discovered several never-before-seen poxviruses that cause illness in people. In one case, a woman in Alaska who thought she had a spider bite turned out to have an infection with a new poxvirus, and doctors never determined exactly how she became infected.

"Poxviruses continue to pose a threat," Dr. Brett Petersen, a medical officer at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Poxvirus and Rabies Branch, said during a talk at an infectious disease conference called IDWeek, held in San Diego earlier this month. For this reason, there is a "need for continued vigilance and increased surveillance" for cases of poxviruses, Petersen said. [The 9 Deadliest Viruses on Earth]

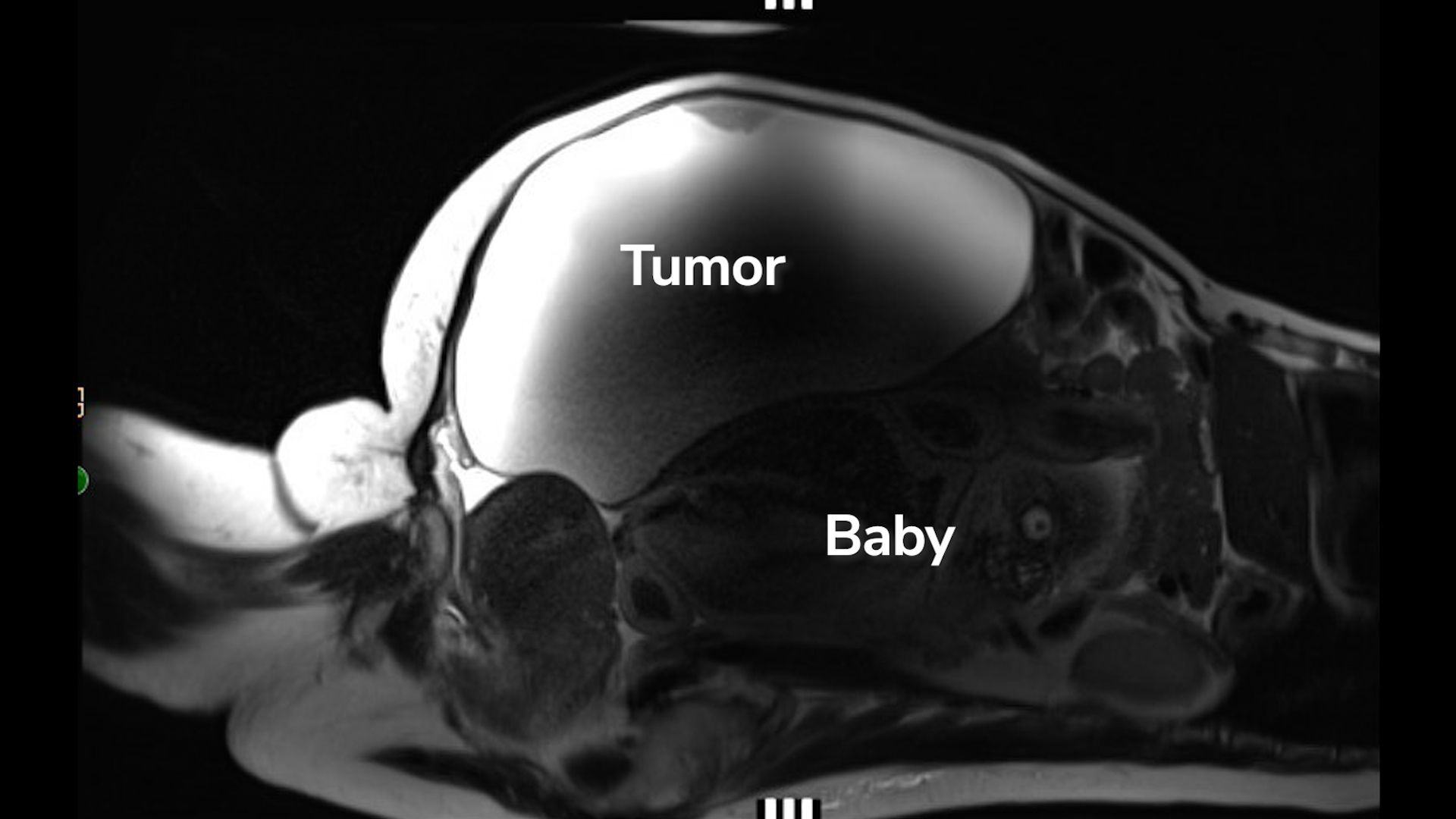

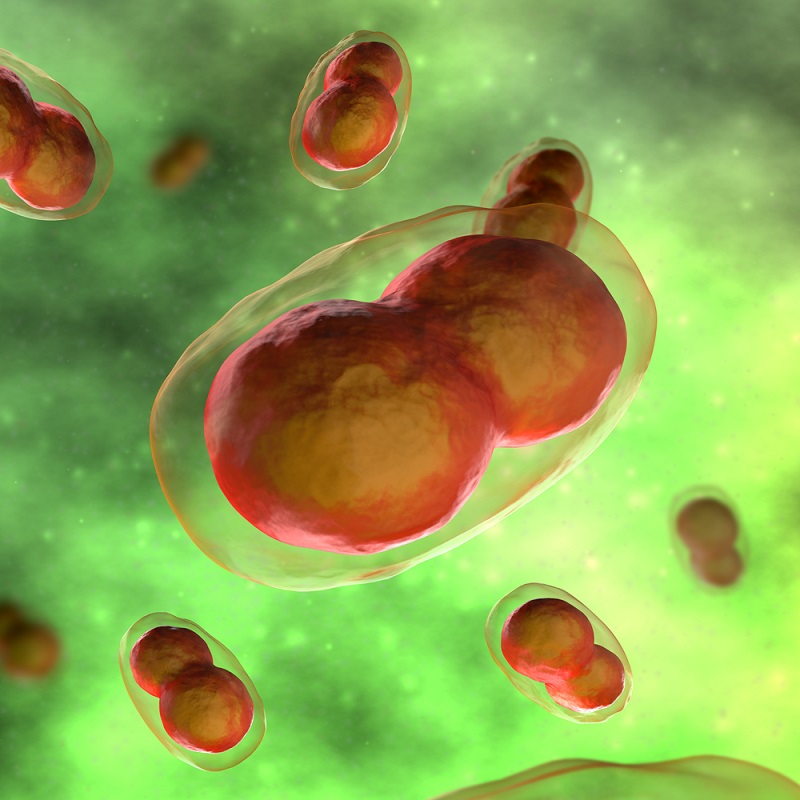

Poxviruses are oval or brick-shaped viruses with large genomes, according to the CDC. Infections with poxviruses typically cause skin lesions or rashes. Perhaps the most famous poxvirus, the variola virus, causes smallpox, a highly contagious and sometimes fatal disease that was declared eradicated from the world in 1980 thanks to a global vaccination campaign, according to the World Health Organization. (Eradication means that cases of the disease no longer occur naturally anywhere in the world.)

But after the eradication of smallpox, researchers saw an increase in cases of some other diseases caused by poxviruses. In particular, there has been a rise in cases of monkeypox, which is closely related to smallpox; both belong to the poxvirus family called orthopoxvirus. (The two diseases have similar symptoms, but monkeypox is less deadly than smallpox: The fatality rate for monkeypox is 10 percent, versus 30 percent for smallpox.)

Human cases of monkeypox occur primarily in Central and West Africa, and the virus is transmitted to humans from the fluids of animal carriers, including rodents and primates.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In a study published in 2010 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers found that since the eradication of smallpox, cases of monkeypox had increased 20-fold in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, from less than 1 case per 10,000 people in the 1980s to about 14 cases per 10,000 people in 2006-2007. [27 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

Other African countries have seen rises in monkeypox as well. In just the last month, 36 suspected cases of monkeypox have been reported in Nigeria, according to The Conversation. If confirmed, the cases would be the first in the country since 1978.

Doctors in the western world also have reason to be on the lookout for monkeypox and related poxviruses. In 2003, the United States experienced an outbreak of monkeypox tied to a shipment of animals from Ghana. In total, nearly 50 confirmed or probable cases of monkeypox were reported in six U.S. states during the outbreak, according to the CDC. "These diseases are never as far away as we think," Petersen said.

Researchers also continue to discover new types of poxviruses in various parts of the world. In the Alaska case, which occurred in 2015, the woman went to the doctor because she had a lesion on her right shoulder, along with fever, fatigue and tender lymph nodes, according to a report of the case, published in June. Her doctors thought she might have chicken pox or shingles, but testing revealed that she had a type of orthopoxvirus that had never been seen before.

It took six months for the lesion to fully disappear, but the woman eventually recovered and did not transmit the infection to anyone else, the report said.

That case shows that there are "previously undiscovered, unrecognized, unknown poxviruses ... that are still being discovered to this day," Petersen said during his talk.

Efforts to discover exactly how the woman contracted the virus turned up empty. She had not traveled out of state, but her partner had traveled to Azerbaijan about four months earlier. Azerbaijan is next to the republic of Georgia, where another new orthopoxvirus was discovered, in 2013. But testing of her partner's items from the trip, such as clothes and souvenirs he brought back, did not show any evidence of orthopoxvirus DNA.

Testing of small mammals near the woman's home (such as shrews, voles and squirrels, which can carry orthopoxviruses), and testing of household areas that the small mammals may have touched, also came back negative. Still, the researchers said they were able to collect only a limited number of mammals from around the home. At this time, the most likely explanation for the patient's infection is that she was exposed to the virus around where she lived, near Fairbanks, Alaska, the report said.

"This discovery of a novel orthopoxvirus is the latest in a growing number of reports of human poxvirus infection published in recent years," the researchers said in their report.

One hypothesis for the increase in such infections is the cessation of smallpox vaccination, because such vaccination may have provided protection against other poxviruses, the researchers said.

"Continued emergence and re-emergence of orthopoxviruses is expected," the researchers wrote.

Petersen also noted that even though smallpox has been eradicated, the virus that causes the disease has not been completely wiped off the planet. Some stocks of the virus still exist in labs in the United States and Russia. And there's also concern that the virus could be used as a bioweapon. Earlier this year, scientists in Canada announced that they had re-created the horsepox virus, a relative of smallpox, in a lab using DNA fragments. The findings suggest scientists could also make the smallpox virus in a lab.

"Unfortunately, we're still talking about smallpox," Petersen said. "[But] hopefully, we'll never see another case."

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.