The Gulf of Mexico's 'Dead Zone' Could Nearly Double in Size This Year

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

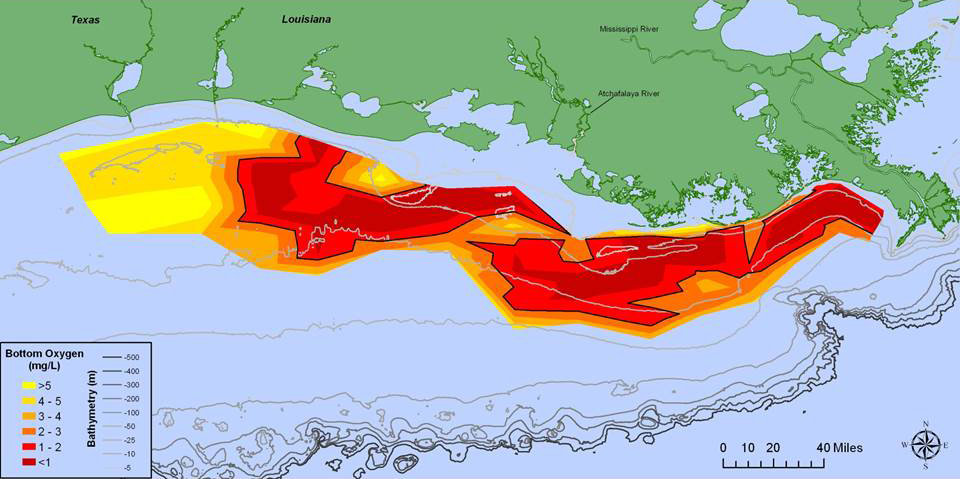

The oxygen-poor "dead zone" in the Gulf of Mexico may be the biggest on record this year, nearly doubling in size to cover an area of ocean as large as Vermont, scientists at Louisiana State University estimate.

The dead zone develops when nitrogen-rich runoff from the Midwestern farm belt pours into rivers and out into the Gulf. That runoff is loaded with fertilizer, as well as nutrients from animal and human waste, and it fuels the growth of algae that die, sink, and decompose, depleting oxygen levels offshore. That drives away marine life in the zone — or kills species that can't escape.

This year, LSU and its partners in the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium estimate the zone will cover more than 10,000 square miles (26,000 square kilometers) off the shores of Louisiana and Texas. High water in the Mississippi River and higher-than-average nitrogen concentrations in the waterway this spring are driving the estimate upward, said Nancy Rabalais, a professor of marine ecosystems at LSU.

RELATED: Coastal Louisiana Is Sinking Faster Than Expected

Scientists from federal agencies put out a smaller estimate of this year's dead zone Tuesday. But even their figure of nearly 8,200 square miles would put 2017 in third place among the 32 years they've tracked the zone, and well above the average of about 5,300 square miles.

The dead zone also has the potential to suck cash out of consumers' wallets: It's led to higher prices for large shrimp, as fishing boats working the hypoxic water end up with a bigger share of smaller, less-valuable shrimp in their nets, Duke University researchers reported earlier this year.

Efforts to tackle the roots of the zone have had little effect so far, Rabalais said. Some farms are adopting practices that reduce the amount of fertilizers and tilling needed to grow crops, "but the percentage of the area in the watershed is quite small."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"There's a federal-state task force to come up with recommendations state-by-state to reduce nutrients," she said. "If you read the details of the forecast and the changes in flows over time, you can see there hasn't been much of a change. Which means the few really concerted efforts to reduce nutrients have been overwhelmed by the usual way of big agribusiness in the watershed."

RELATED: Marine Reserves Renew Hope in the Fight Against Climate Change

Researchers will attempt to confirm the area's size with a research cruise in July. Rabalais said the zone might be smaller if a major tropical storm churns up the Gulf, mixing more air from the surface into the water. A big storm could mean a dead zone 30 percent smaller than estimated, the LSU report notes — but that would leave it nearly 50 percent larger than average.

With Tropical Storm Cindy headed for an expected landfall near the Texas-Louisiana state line, "The waves have really picked up," Rabalais said. That's expected to boost oxygen levels temporarily, "But it will settle back down and go back to low oxygen."

Originally published on Seeker.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus