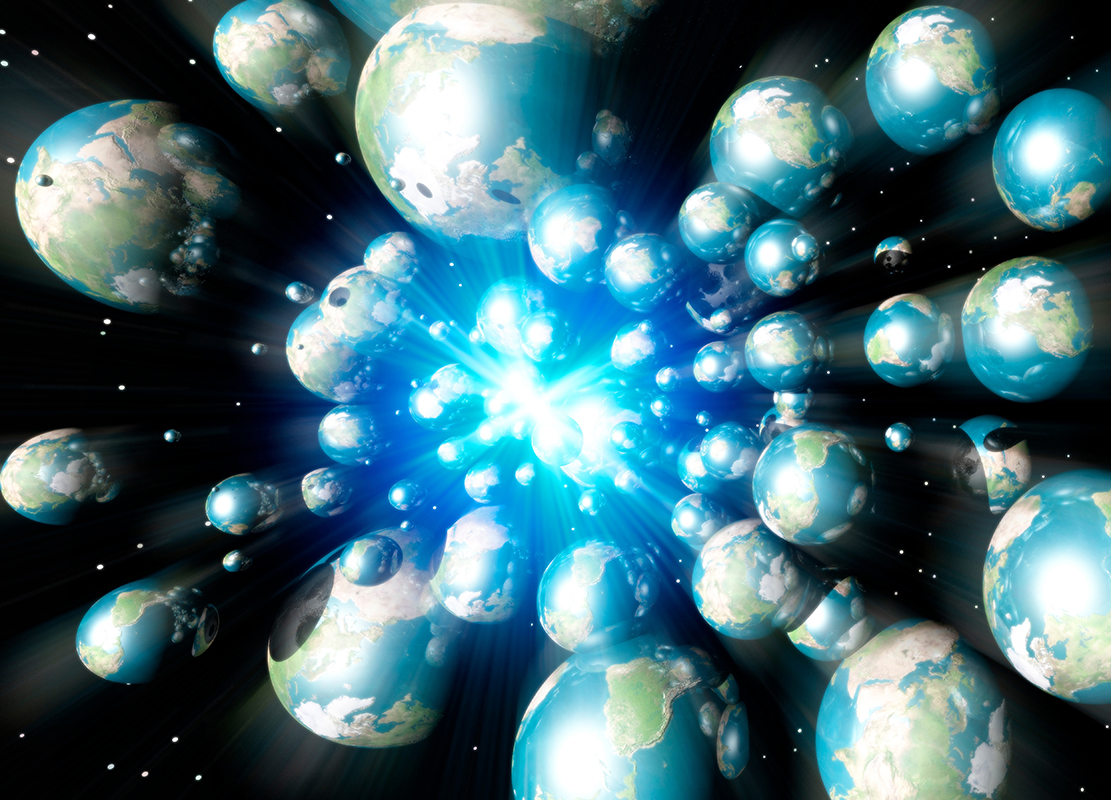

If We Live in a Multiverse, Where Are These Worlds Hiding?

WASHINGTON — By some estimates, the known universe may contain as many as 2 trillion galaxies, with the average galaxy holding approximately 100 million stars and untold numbers of planets. But could there be multiple copies of the entire universe as we understand it?

The concept of a multiverse — worlds that invisibly coexist alongside us, perhaps representing versions of reality that are near-identical to our own — is a pervasive idea in sci-fi, and one that has intrigued generations of physicists as well as science-fiction creators and fans.

While scientists have yet to find any evidence that multiverses exist, there are a number of hypotheses that use the laws of physics to explore the possibility of multiple universes, sometimes challenging our understanding of reality itself in the process, Erin Macdonald, astrophysicist, engineer and self-proclaimed "massive sci-fi nerd," explained during a panel on Saturday (June 17) at Future Con, a festival that highlighted the intersection between science, technology and science fiction in Washington, D.C. [Top 5 Reasons We May Live in a Multiverse]

Our universe exists within the fabric of space-time — 3D space combined with time, to create a 4D continuum, explained Macdonald. But scientists can't say for sure what space-time looks like, which means it might hold countless universes that are invisible to us, she said.

The simplest version of the multiverse concept is the so-called mirror universe, in which a single alternate universe closely parallels ours, but is also its opposite — such as the "Mirror, Mirror" episode of the original "Star Trek" television series, in which a landing party mistakenly beams up to a different version of the Enterprise, occupied by more brutal versions of their familiar crewmates.

Another perspective on the multiverse is the brane universe, which describes our universe as one membrane in a vast, possibly infinite stack of membrane universes, but with no connection or means to communicate between them, Macdonald said.

Multiple universes might also exist within contained bubbles of space-time, a concept explored in the video game "Bioshock Infinite." By this reckoning, inhabitants of two universes could theoretically interact should their "bubbles" connect to each other directly, according to Macdonald.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Quantum universes appear more commonly in sci-fi, Macdonald said. This idea suggests that every decision a person makes spawns a new timeline, creating a new and self-contained universe that follows a different path. Science-fiction writers crafting time-travel stories frequently invoke the rules of quantum universes to explain how characters can travel to the past and not erase their own existence — their every choice births new universes entirely, leaving the universe that was their origin intact.

But perhaps the most disturbing premise of all is whether the universe we perceive as real is, in fact, a simulation of some kind, as in the movie "The Matrix."

"Would you want to know if you were a simulation, but had no control? Could we test if we were in a simulation if we were all just code?" Macdonald asked the audience. For now, plenty of questions remain unanswered — about multiple universes and the reality of our own, she said.

"None of these can be proven — but they're fun to think about," Macdonald said.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works. She is the author of the book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control," published by Hopkins Press.