Orangutans Nurse Their Babies For 8 Years

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

For American parents, breast-feeding past a year or two tends to be a fraught topic. Orangutan mamas, on the other hand, are in it for the long haul: New research finds that orangutan babies nurse for eight years or more.

Though orangutans were known to be long-term lactaters, the new study published today (May 17) in the journal Science Advances revealed nursing behavior extending more than a year past what had previously been reported. The researchers used chemical signatures in baby orangutans' teeth to track nursing, so they were also able to determine how much milk the apes took in. Scientists had thought that young orangutans nursed consistently in small amounts over long periods, said study researcher Manish Arora, a professor of environmental medicine, public health and dentistry at Mount Sinai's Icahn School of Medicine in New York.

"What we found instead was that this was quite cyclical," Arora told Live Science. "They go through regular periods of increased maternal milk intake whenever there is a sharp decline in fruit availability." [8 Human-Like Behaviors of Primates]

Orangutan lactation

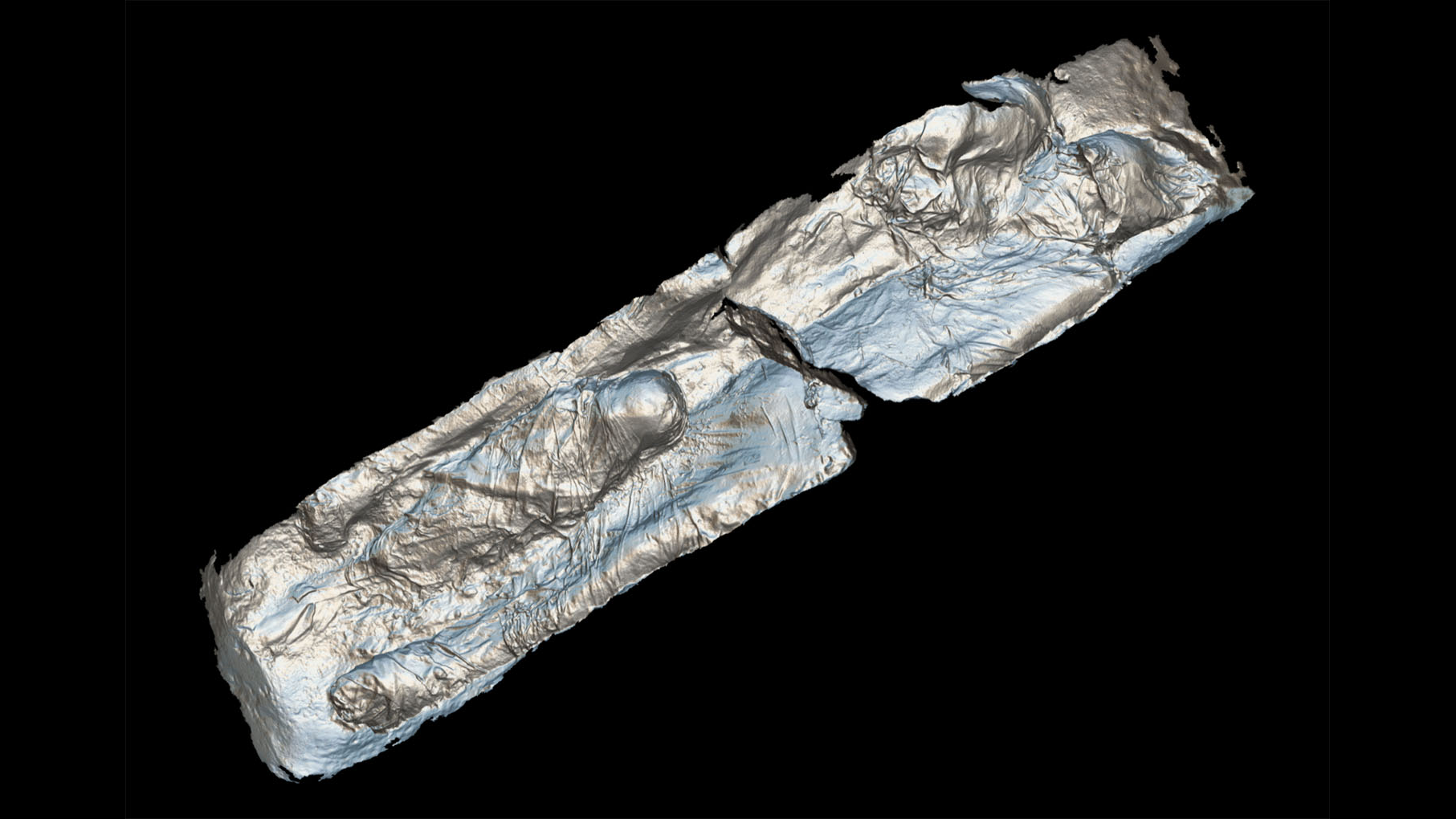

Orangutans are a reclusive, tree-dwelling species, so it's difficult for field biologists to tell whether or how much they're nursing their infants. However, nursing leaves behind biochemical traces in the body, particularly in the teeth. Arora and his colleagues analyzed levels of an element called barium in the molars of four young Bornean and Sumatran orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus and Pongo abelii, respectively). The molars were held in biology collections and provided by study author Tanya Smith, an evolutionary biologist at Harvard University.

Barium is chemically similar to calcium, said study author Christine Austin, a postdoctoral researcher in environmental medicine and public health at Mount Sinai. Female mammals pull calcium from their bones to make milk. When they do so, barium tends to follow. Using a laser, Austin and her colleagues stripped tiny portions of tooth away and analyzed the composition with mass spectrometry, a method that sorts elements within a sample by mass so that they can be identified.

They discovered a pattern in which baby orangutans nurse almost exclusively for the first year of life, adding solids to their diet only between the ages of 12 months and 18 months. After that, the barium levels in the teeth decreased, indicating a lower milk intake. (Solid foods do contain barium, Arora said, but it is not as available for absorption to the body as the barium in maternal milk.) After infancy, the barium levels would spike again approximately once a year, presumably during seasons when fruit and other solids weren't available. One female Bornean orangutan in the study nursed until 8.1 years of age, the researchers found, while a male that died at age 8.8 was still nursing in the last months of his life. Female orangutans mature to adulthood at about age 12, while males hit reproductive age around 15. [In Photos: Adorable Orangutan Shows Off Knot-Tying Skills]

"These orangutans are very interesting primates because they live in very isolated environments and very harsh environments," Arora said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The evolution of nursing

The team is studying other ancient primate teeth and is in the midst of a large study of the shed baby teeth of modern children. The aim, Arora said, is to compare this objective measure of milk intake to developmental outcomes in human kids.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus