Pollution Turns Leaves Magnetic

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Tiny particles of pollution that are harmful to human health stick to tree leaves and leave a trace magnetism, a new study finds. More pollution is found stuck to leaves of trees near busy roadways than those in less trafficked areas.

The pollution-trapping leaves could serve as an easy, inexpensive way to monitor pollutant levels, researchers say.

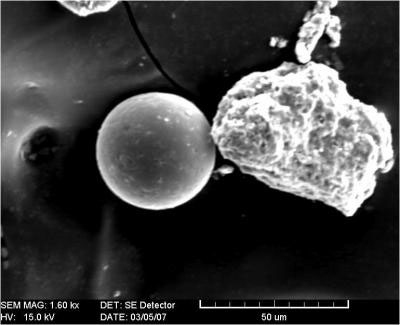

Scientists in Europe first noticed that a type of pollution called particulate matter was sticking to leaves in industrial areas. Particulate matter is created by the combustion of fuel and can include many different compounds. The ones these scientists detected were metallic pollutants — such as iron oxides from diesel exhaust — that left a magnetic trace on the leaves (though the leaves themselves don't become magnets).

The bumpy, wavy surfaces on the leaves easily trap the floating particles of pollution, which either remain stuck to the leaves surface or can even grow right into the leaf.

The leaves are "pretty efficient particle collectors," said geophysicist Bernie Housen, of Western Washington University in Bellingham, Wash.

Housen set out to see if this magnetic pollution could be detected on Bellingham's leaves as well, and if there was a different between leaves of trees in busy city areas than in more rural ones.

Housen and his colleague Luigi Jovane collected several leaves from 15 Bigleaf Maple trees (Acer macrophyllum) in and around Bellingham in late June. Five of the trees were next to roads with busy bus routes; five sat on parallel, but quieter streets; five were in a nearby rural area.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The leaves along the bus routes showed two to eight times more magnetism than those from the nearby quieter streets and four to 10 times more magnetism than leaves from rural areas.

The findings, presented last weekend at the meeting of the Geological Society of America, suggest that leaves could act as a simple, cost effective way to monitor pollution, Housen said.

Monitoring particulate matter is important because of the danger it poses to human health. The tinier the particles are, the deeper they can penetrate into lungs, with consequences to health that include breathing and heart problems.

Housen told LiveScience that he hopes to expand his leaf study to look at different sources of pollution, a broader region and the potential effects to the leaf (and the plant it grows from).

- Other Impacts of Pollution

- Houseplants Make Air Healthier

- What Is Smog?

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus