Ice Watch: Satellites Reveal How Glaciers Creep and Crawl

SAN FRANCISCO — Though they appear to be frozen giants, glaciers and ice sheets can move and change in unexpected ways over time, according to a new database that is now tracking the movement of ice, including the extent of its melt and slow creep into the sea.

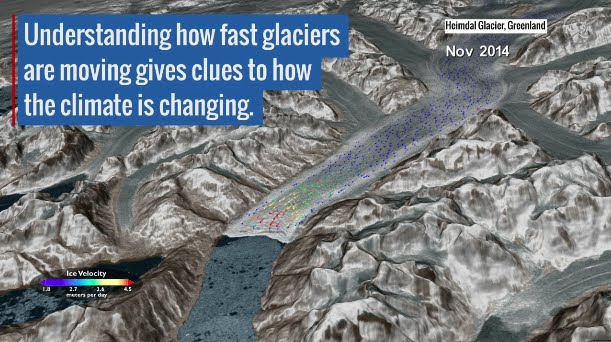

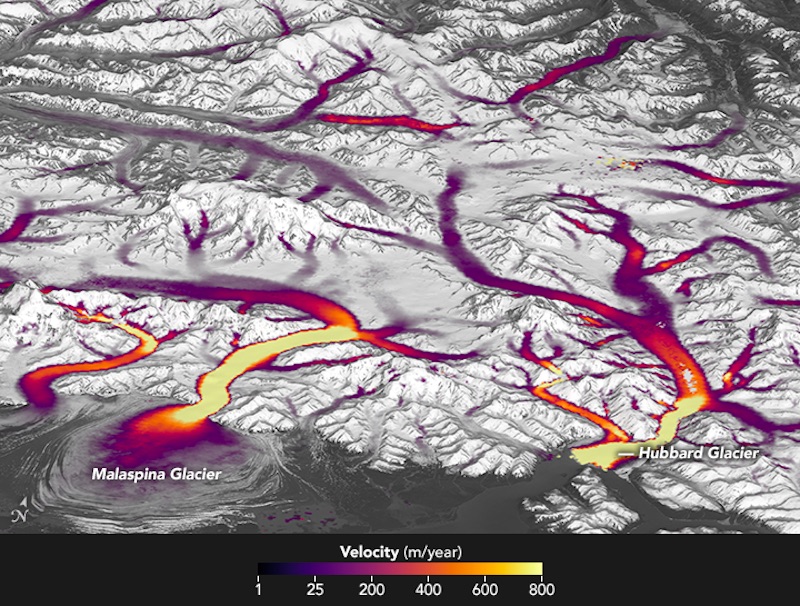

With imagery and data from Landsat 8, an Earth-monitoring satellite, scientists at NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) are tracking the speed of glaciers' movement and melt. These observations are in"near real time" and help to better predict how global sea levels will be affected by climate change, the researchers said.

The so-called Global Land Ice Velocity Extraction (GoLIVE) project uses observations from Landsat 8, as well as historical data from older Landsat satellites. By comparing data from Landsat 8, which images the Earth's entire surface every 16 days, the GoLIVE team can track subtle changes in the glacier, such as bumps and dunes, the researchers said. Ted Scambos, a senior research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado Boulder and the Colorado lead for the GoLIVE project, said Landsat 8 can even capture changes in a glacier's "skin." [Photo Gallery: Life Inside a Glacier]

"Not only are we able to map the glacier chunks where there are large crevices and high-contrast features, but [we can] also [map] the surface of the ice sheet even where it's smooth, down to these snow-dune features," Scambos said here Monday (Dec. 12) in a news briefing at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union. "By being able to track with higher precision what the surface texture looks like, we can actually map the flowing skin of the ice sheet."

Such observations were previously extremely difficult, if not impossible, for researchers to make. The first time scientists studied a surging glacier in detail, they did so via annual field research, said Mark Fahnestock, a professor in the Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Scientists visited that glacier every year for 15 years, putting down stakes during each visit. They then surveyed those stakes to determine any changes in the glacier.

But these very large, remote glacial systems in Alaska could experience sped-up melt events for months without scientists taking notice, Fahnestock said.

"We've entered an era where instead of a pilot telling us a glacier is changing, or instead of a field party recognizing a change in one of the 242 glaciers followed, we are actually following on a month-by-month basis with Landsat 8," Fahnestock said. "We are now watching all of the outlet glaciers on Earth change in near real time."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Twila Moon, a research scientist at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom, joked that rather than researching several glaciers over hundreds of years, the GoLIVE project allows for the study of hundreds of glaciers over several years.

The project could also "launch a thousand ships" in terms of international research into glaciers, Scambos said. As a public database, the project will allow for scientists around the world to conduct more effective field research, according to the GoLIVE time, because scientists will have better "situational awareness" of a given glacier before researching it in person.

One other important implication, Scambos said, is that the data makes it clear that the glaciers are melting.

"By presenting the data in an easy-to-understand way, it makes it obvious what's going on in the world's eyes, and that the world is changing and that there's no attempt to hide it at all," Scambos said. "It makes it plain as day that we have a changing Earth."

Original article on Live Science.