Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Introduction

Scientists recently rediscovered a mysterious sea creatures called a Bathochordaeus charon lurking in the waters of Monterey Bay, California. The creature, which looks a bit like a psychedelic slinky, is a giant larvacean, a type of filter feeder that creates a diaphanous mucus "house" to collect food that is directed towards its mouth. Though a naturalist on an expedition first discovered it more than a century ago, no one had confirmed its existence in the ensuing years. [Read the full story on the mythical sea blob]

Snowy body

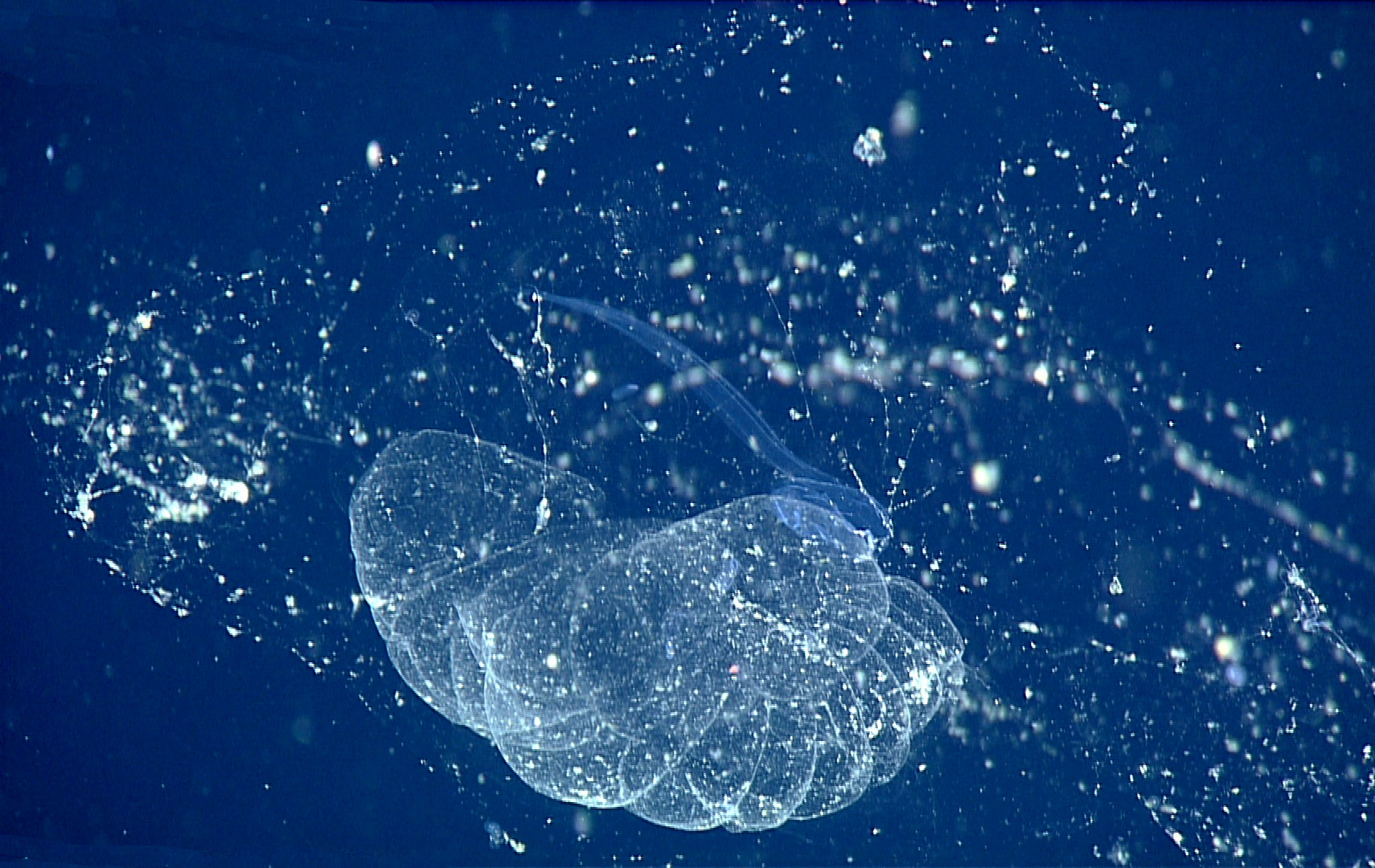

B. charon, which was named by its discoverer after the ferryman who transports souls across the river Styx in Greek mythology, uses its globular mucus house to trap particles that are then fed into its mouth via a feeding tube. The bright dots on its house are called marine snow.

Tadpole body

Though B. charon is a giant larvacean, it's body is only big relative to others of its kind, which could be just a few millimeters in size. B. charon's body is about 3.5 inches (9 centimeters) in size, though its mucus house may be 3.3 feet (1 m) in length. Here, a larvacean swims freely, unencumbered by its house.

Drifting through the water

A giant larvacean, Bathochordaeus charon (the blue tadpole-like animal in the center of the image), surrounded by its inner "house" (the lobate object below the larvacean) and part of it's outer "house (the diffuse mucus web). Scientists weren't sure that B. charon was distinct from another giant larvacean species, called B. stygius, because the original specimens used to define the species were lost and subsequent sightings were never well-described.

Anatomic differences

However, when researchers from MBARI piloting a remotely operated vehicle saw a giant larvacean floating in the bay recently, they carefully collected it and preserved it. Looking up close at the anatomy, the differences between B. charon and B. stygius were clear.

Differences up close

The inner filter (“house”) of Bathochordaeus charon (a–c) compared to B. stygius (d–f) are readily distinguishable in high-definition video, taken by MBARI ROVs. Bathochordaeus charon is larger in size relative to its inner filter (if) than is B. stygius, which also has more conspicuous supply passages (sp) through which water is diverted to either filter. The inner filter of B. charon is less convoluted than B. stygius and has fewer chambers (compare c, f). Plate B demonstrates that the spiracles (s) can be seen on high-definition video. Scale bars ~ 2 cm, a–f

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus