Climate Experts Weigh in on Trump's Election Win

The election of Donald Trump as the nation's next president spurred celebration in some quarters and dismay in others, including among those concerned about the steady warming of the planet.

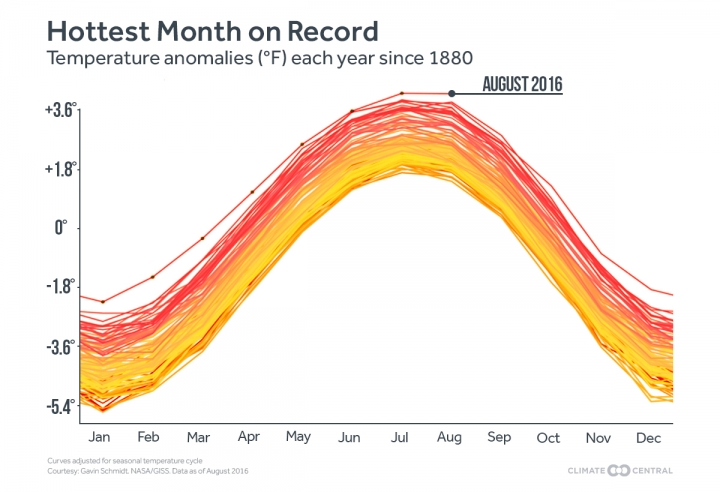

The unrestrained emissions of heat-trapping greenhouse gases have altered the Earth's climate, raising sea levels, impacting ecosystems, and increasingly the likelihood of extreme weather. In terms of numbers, the world’s temperature has risen by more than 1 degree Fahrenheit since 1900 and 2016 is expected to be the hottest year on record.

Though climate change was not a major topic in much election coverage — there were no questions on it during the three presidential debates — many climate scientists and policy advocates supported Clinton. They expected that she would continue policies enacted by the Obama administration, such as the Clean Power Plan and the signing of international agreements to limit warming.

Trumps comments on climate change have included calling it a hoax and warning that Environmental Protection Agency policies are costing the country jobs, though he has talked about the importance of maintaining clean air and water. He has suggested he will pull out of the landmark Paris agreement and scuttle the Clean Power Plan, as well as boost the domestic coal and oil industries.

While the U.S. is only one country, it is a linchpin to the viability of international agreements and to moving the needle on limiting warming.

In response to Tuesday's landmark election, Climate Central reached out to climate, energy and policy researchers to see how they think a Trump presidency will impact climate research and efforts to limit future warming and mitigate what has already happened. We also asked what they think climate scientists should be doing in the coming weeks, months and years, including what they may personally be doing. Their answers have been lightly edited for clarity and brevity:

Jennifer Francis, sea ice researcher at Rutgers University: If President Trump acts on statements he made during the campaign, we are likely to see any federal efforts to curtail fossil fuel burning go up in smoke. I fear that funding for any scientific research related to the environment will be further cut by an unrestrained science-phobic Congress, even as we become ever more confident of the myriad ways that climate change is costing the U.S. economy billions of dollars, contributing to food and international insecurity, and disrupting daily life. As an optimist, I hope that a President Trump will become more open-minded than the candidate Trump and allow facts to guide his presidential decisions. I also hope that as president he will take his grandchildren to visit our great national parks and see the beauty that will be destroyed if he ignores those facts.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mother Nature did her share to influence this election by dishing up a smorgasbord of record-breaking heat, flooding, drought, and storms — yet, climate change was a non-issue. We know it's adversely affecting wildlife, agriculture, fisheries, outdoor sports, transportation, you name it — so clearly scientists of all stripes need to tell this story better. I will be redoubling my efforts to help people recognize impacts of climate change on their own lives, and also see the solutions that must happen to reduce the mess we leave for our children.

Jacquelyn Gill, paleoecologist at the University of Maine: We have just elected the only climate denying president in the free world, with a Young Earth Creationist vice president. It's hard to predict exactly how this will play out in terms of impacts to combat and mitigate against climate change, but one of the most immediate threats will be to the funding and agencies that support climate change research. Trump has gone on the record stating he'd cut funding for climate science, which will directly jeopardize ongoing efforts to understand how the climate system works, how to predict the impacts of climate change, and what the effective strategies for mitigation should be.

U.S. Senate Could Block Landmark HFC Climate Treaty 3 Ways Trump Could Abandon the Paris Climate Pact Trump's Presidency Poses Serious Risks to the Climate

I worry that Trump's election will only rejuvenate the ongoing assault on climate scientists, both in terms of internet harassment and in Congress. In my opinion, scientists should be taking steps to protect the security of their online communications, their data, and their personal information. We should be supporting efforts like the Climate Legal Defense Fund. We should be careful about bringing new students into our labs while the future of science funding is so uncertain. We should be putting communication networks in place, reaching out to grant program officers, university administrators, and legislators, and doing what we can to advocate for the importance of our research and academic freedom at every level.

And even though it's scary, we need to be reaching out to the public, now more than ever. We need to find our own outreach communities and connect with those people, and to undertake efforts to humanize climate science. And we need to work with the folks who aren't scientists who are on the ground, on the front lines of climate change and climate justice, to make sure that we amplify their voices and pitch in where we can. This is going to be especially crucial for those of us who are in the most protected groups — white men especially.

Katharine Hayhoe, climate modeler at Texas Tech University: I work with cities, states, and provinces — helping them prepare for a changing climate, building resilience to the impacts we can't avoid, cutting carbon to reduce the impacts we can avoid. Cities like Washington, D.C., Chicago, and even tiny Georgetown, Texas, are at the forefront of this global movement. A president hostile to climate policy may be able to affect federal and even international action: but they can't stop cities and that's where the momentum is. That's what gives me hope.

Andrew Hoffman, sustainable development expert at the University of Michigan: Trump's election throws the future of environmental policy, both in the U.S. and globally, into confusion. His stated and tweeted positions on climate change, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Paris climate accord, the Clean Power Plan and many other related issues suggest that the future of much of the programs and policies of the past administration, indeed many from administrations going back to President Nixon's formation of the EPA, are in question. That said, Trump's positions have been uneven (for example, while deriding some environmental policies, he has endorsed programs by the National Wildlife Federation to protect the Great Lakes; announcing "let's make the Great Lakes great again") and some seem to have been hastily announced (such as his tweet that climate change is a Chinese plot). Let's wait and see how his positions solidify in the coming days of his administration. One aspect of Trump's campaign has been his unpredictability.

I would also add that I wrote this essay to warn that he may be following a similar path that Reagan started down and had to stop. Reagan tried to stop the actions of the EPA and faced a latent interest among the general public on the environment that was aroused by his disregard for environmental policies.

Mark Jacobson, clean energy researcher at Stanford: I'm most concerned with how a Trump presidency will affect solutions to climate change, air pollution, and energy security. Fortunately, the cost of wind and solar are very low now and dropping still, and clean-energy technologies and startups are widespread, so we have momentum. At the state level, many states are moving to clean, renewable energy. It is still in the economic interest of Republicans and Democrats to expand clean, renewable energy. In fact, the five states with the highest fraction of electricity from wind are all "red" states that voted for Trump. Those countries that move faster toward clean, renewable energy will create more jobs, develop their economies faster, become more energy independent, reduce catastrophic risk, including terrorism, associated with centralized plants, and live healthier and longer, so this should be an incentive to keep moving in the right direction. Since most efforts to solve the problems have been at the state level over the past four years in any case (e.g., California, New York, and even inadvertently in Iowa and South Dakota with their expansion of wind), I am confident state and local steps can continue.

I will continue to do what I do, namely try to understand and solve the problems. There is nothing that an unsupportive president can do to stop my efforts.

Ralph Keeling, director of the CO2 program at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography: It's not easy to formulate responses at this point. It's clearly too early to tell what Trump will do to change the landscape on climate mitigation. For now we will be waiting to see how much his policies will be guided by the sometimes extreme views that guided his campaign — such as being in denial of the climate problem. It's certainly easier to be in denial from the sidelines than from being in the driver's seat, so there's hope that a more reasoned approach will follow.

The main step for the climate scientists is to keep working on the science. If we end up on a slower track on mitigating climate change, this just means we need a faster track on adaptation and preparedness. There's a lot on the plate of the scientists regardless.

Michael Mann, paleoclimate researcher at Penn State: A Trump presidency might be game over for the climate. In other words, it might make it impossible to stabilize planetary warming below dangerous (i.e. greater than 2°C) levels. If Trump makes good on his campaign promises and pulls out of the Paris Treaty, it is difficult to see a path forward to keeping warming below dangerous levels.

It is time for introspection and contemplation. I’m still in the process of letting this sink in.

Laura Tam, sustainable development policy director at SPUR: As a policy analyst and advocate for local climate action, I can tell you that the urgency of sub-nationals and cities to take action to go fossil-free is even more important, and we should set up our systems to do this without the federal government, and perhaps in spite of it. The demonstration of the viability of 100 percent renewables for all energy needs can happen here in California and when we demonstrate the economic and environmental superiority of this model, the nation will not be long to follow. It will become inevitable. A Trump presidency will make local and state action even more urgent.

David Titley, climate and weather risk researcher at Penn State: Many black swans have taken flight this year. One thing science teaches you is that systems frequently revert to the mean. So, as dark as everything looks at this moment for fixing our climate, we need to have hope that we won't realize the worst case. If there is a silver lining it's that Trump does not seem bound by whatever he has said previously. So perhaps he will see the wisdom or at least self-interest, in investing in non-carbon, U.S.-produced, energy.

The climate community has a huge challenge ahead, to frame this issue in a way that will resonate with the likely president-elect. It may not be possible but it would be negligent to not even try.

You May Also Like: Trump's Presidency Poses Serious Risks to the Climate Toasty October Keeps U.S. on Track for 2nd-Hottest Year 'Critical Moment' as UN Climate Talks Resume The World Isn't Doing Enough to Slow Climate Change

Originally published on Climate Central.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.