Valley Fever Fungus Invades the Brain in 3 Rare Cases

NEW ORLEANS — In rare cases, the fungus that causes valley fever can also infect the brain, a new study finds.

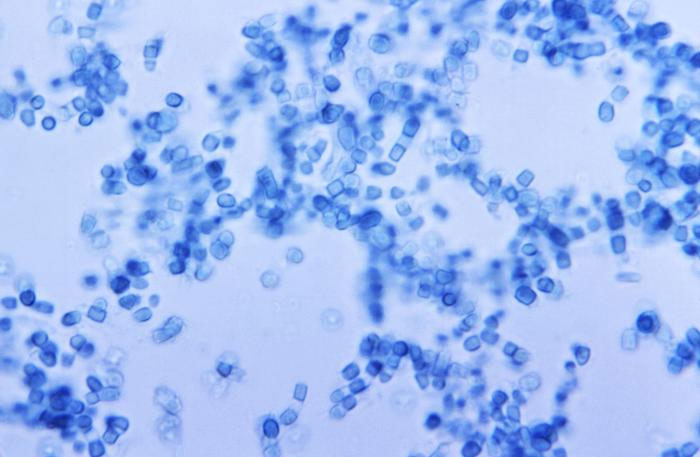

In the U.S., valley fever mainly strikes people in the Southwest. It is caused by the Coccidioides fungus, which is found in the soil in that part of the country. When a person inhales the fungal spores, he or she may develop mild to severe lung problems, including pneumonia.

In some instances, however, the fungus can go dormant in a person's body following an infection, only to become "reactivated" later in a different part of the body, said Dr. Samiollah Gholam, an internal medicine resident at Kern Medical in Bakersfield, California, and a co-author of the new study. [10 Bizarre Diseases You Can Get Outdoors]

Typically in these cases, the infection spreads to the person's bones or the lining of the brain, called the meninges, Gholam told Live Science. If the infection spreads to the meninges, a person can develop meningitis, which is inflammation of the meninges, he said.

But the new report shows that in very rare cases, the infection can also spread to the white matter of a person's brain, called the parenchyma, Gholam said.

In the study, the researchers reviewed all cases of valley fever that occurred at Kern Medical between 1987 and 2014 that had spread to the central nervous system. Of the 153 cases they identified, just three involved the white matter of the brain. All three cases were in men.

The three cases identified in the study brought the total number of "intraparenchymal" cases reported in the medical literature since 1905 up to 42, according to the study, which was presented on Oct. 28 here at IDWeek 2016, which is a meeting of several organizations that are focused on infectious diseases.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If the disease does spread to the white matter of the brain, it can be difficult to diagnose, Gholam said. The fungal infection causes lesions in the brain that can show up on a brain scan, but a person's symptoms will vary, depending on where the lesions form, he said.

In one case, for example, the man had stroke-like symptoms, including a loss of muscle coordination and slurred speech, Gholam said. The most common symptoms in the three cases were headaches and altered brain functioning, according to the study.

Ultimately, doctors need to test a person's cerebrospinal fluid to confirm a diagnosis of valley fever in the brain, Gholam said.

In all three cases, the men were treated with anti-fungal medications and their symptoms improved, Gholam said. The disease can be fatal, however, if it is not treated, he said.

A person doesn't need to have a severe case of valley fever for the disease to spread and re-emerge in another location in the body, Gholam noted. Most healthy people do not even develop symptoms after inhaling the fungal spores, but an infection can still emerge in the future, he said.

The most common site for the fungus to spread in the central nervous system is the meninges, according to the study.

It's not entirely clear why the fungus becomes reactivated in some people; however, genetics may make some people more prone to this type of infection, Gholam said.

The findings have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Originally published on Live Science.