Tallest Mountain in US Arctic Crowned

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Mountaineers and other adventurers now have a more accurate map of which peaks in the U.S. Arctic are the tallest.

Though Denali is the uncontested highest peak in North America — with a summit elevation of 20,310 feet (6,190 meters) — there has been a more than 50-year debate over which U.S. mountain can be crowned the tallest beyond the Arctic Circle. U.S. Geological Survey topographic maps from the 1950s show either Mount Chamberlin or Mount Isto as the highest mountain in the eastern Alaska Arctic region.

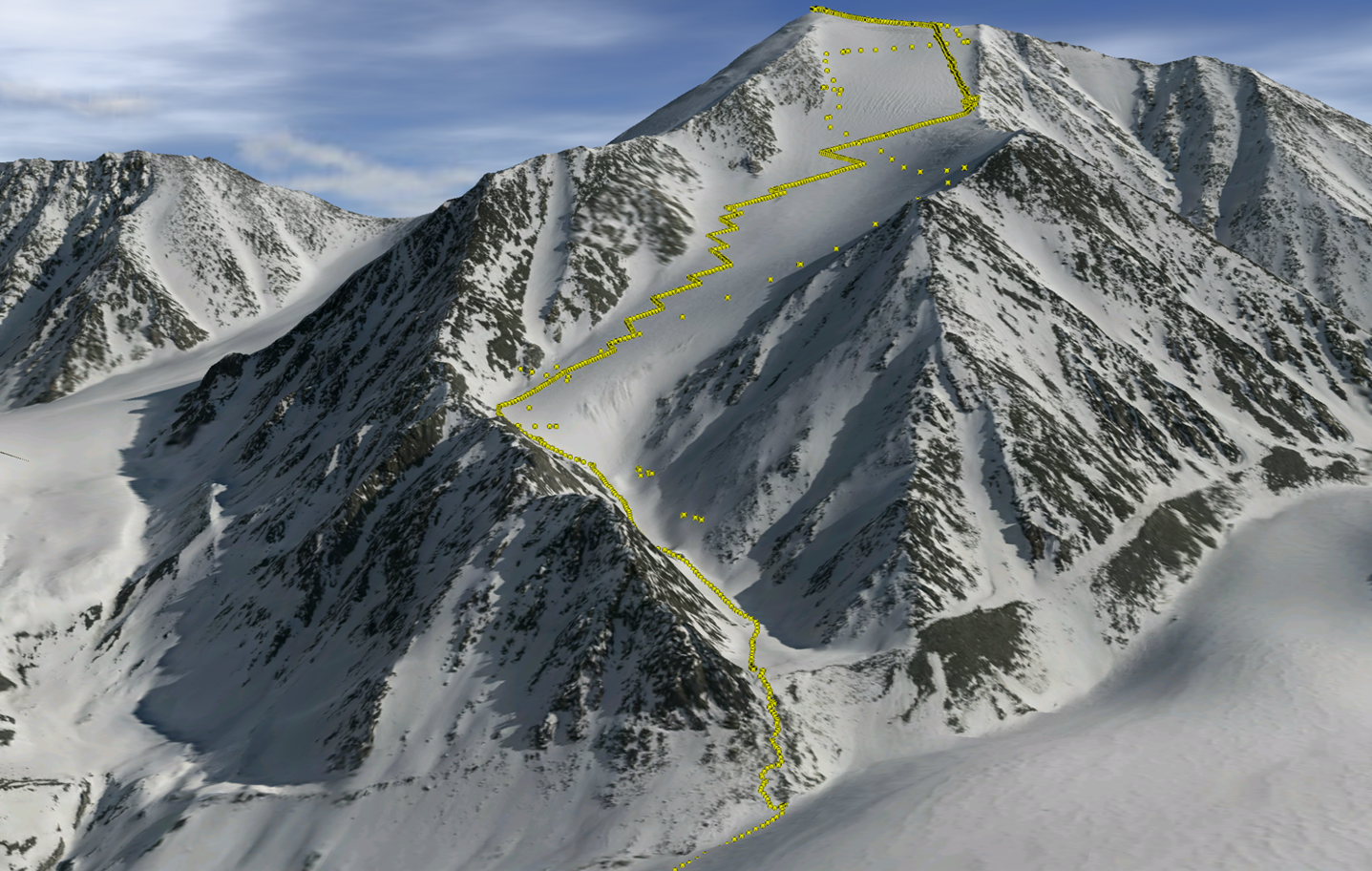

A new mapping technique, known as fodar, has finally settled the debate. At 8,975.1 feet (2,735.6 m), Mount Isto is the tallest peak in the U.S. Arctic, and Mount Chamberlin (at 8,898.6 feet, or 2712.3 m) is only the third highest. [Photos: See the World's Tallest Mountains]

Fodar, which uses airborne photography to survey and map terrain, revealed a third tall peak: Mount Hubley. This mountain surpassed Mount Chamberlin by about 16 feet (5 m) of height, claiming second place in the list of highest U.S. Arctic mountains.

Glaciologist Matt Nolan, lead-author of the study published today (June 23) in the journal The Cryosphere, had been mapping glacier volume change using the fodar technique, which he invented.

Mapping mountains

"These mountain peaks just happened to be located in the same area as the glaciers we were studying, and several of the peaks ended up in our maps," Nolan, of the University of Alaska Fairbanks, said in a statement. "Because we were interested in understanding the performance limitations of fodar in steep mountain terrain, it seemed a natural fit to combine this validation testing with settling the debate on which peak was the tallest."

Fodar is similar to airborne LiDAR (Light Detection And Ranging), which uses aircraft-mounted lasers to scan a landscape and create 3D maps of the terrain, but is a more affordable mapping option, Nolan said. [The University of Alaska has a more detailed explanation of how fodar works.]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The core equipment is a modern, professional DSLR camera; a high-quality lens; a survey-grade GPS unit; and some custom electronics to link the camera to the GPS," Nolan explained. And, he added, fodar can be operated by the pilot flying in a small, single-engine plane.

Summiting the Arctic

Nolan worked with champion American skier and ski mountaineer Kit DesLauriers to map the peaks from the air and on the ground. While Nolan flew a Cessna 170B and used his fodar technique, DesLauriers was climbing up and skiing down the mountain range.

DesLauriers, who was the first person to ski down the Seven Summits, tracked her position using the same GPS unit Nolan had in his plane.

"Instead of a normal rest stop to eat and hydrate, I used the rare moments standing still to note my location and time in a field journal so that Matt could have as much data as possible to compare our measurements," DesLauriers said in the statement. "The process made climbing the peaks, which took on average a 10-hour summit push after a multiday approach, more difficult but also more rewarding."

The challenging expedition was necessary, Nolan said, as it offered control points on the ground to compare the airborne measurements to, ensuring accuracy.

Using fodar

Now that fodar has settled the Arctic peaks' debate, Nolan said the mapping technique can be used for measurements beyond mountain heights.

"Though determining peak heights was a fun and useful study, our primary use for fodar is in change detection in the cryosphere [the planet's frozen regions]," Nolan said.

The same maps created from fodar to measure peak heights can help scientists understand how snow and glacier melt will affect the region, Nolan said. He has used fodar to measure coastal erosion, permafrost melt, landslides and more.

"The possibilities are truly unlimited," he said.

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus