How Kevlar Saved an Orlando Police Officer's Life

A helmet made of Kevlar saved the life of an Orlando, Florida, police officer on Sunday (June 12) after police engaged in a gun battle with a man who killed 49 people and injured 53 others at a gay nightclub, according to news sources.

Thanks to its unique chemistry, Kevlar body armor has saved the lives of countless people who were wearing it. In a tweet Sunday morning, the Orlando Police Department applauded the tough fiber: "Pulse shooting: In hail of gunfire in which suspect was killed, OPD officer was hit. Kevlar helmet saved his life."

But how exactly does Kevlar protect people? Live Science spoke with two material scientists to learn more. [Top 10 Inventions that Changed the World]

Discovered by DuPont scientist Stephanie Louise Kwolek in 1965, Kevlar is essentially "a high-performance plastic," said Richard Sachleben, a member of the American Chemical Society's panel of experts, who has worked in the pharmaceutical industry in the Boston area for 40 years as a chemist.

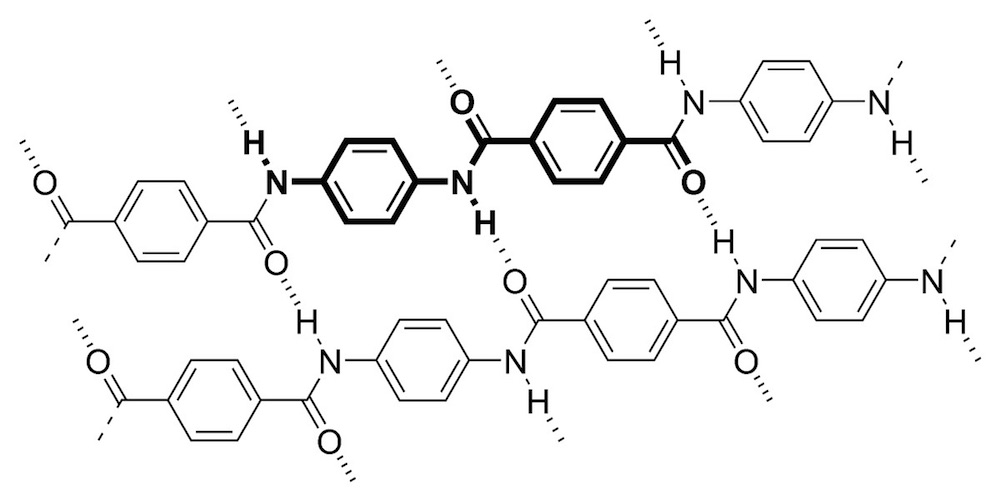

The synthetic material is made of polymers — essentially long chains of molecules. To better visualize these polymers, imagine a long beaded string, with the beads representing different molecules.

Two features make this polymer ultrastrong, Sachleben told Live Science: Its molecules, or "beads," are strongly attracted to one another; and hydrogen bonds — the same bonds found in DNA, as well as water molecules — keep the "beaded strings" tightly interlocked with their neighboring beaded strings, Sachleben said.

"When a bullet hits that piece of Kevlar, it starts pushing those molecules apart, those chains apart," he said. "But they're stuck together pretty tight."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It takes a lot of energy to push the molecules and chains apart, he said. Even a high-energy projectile, such as a bullet, has trouble punching its way through. Instead, the Kevlar absorbs the energy from the projectile and spreads it out across all of the chains — that is, the energy is dissipated across the helmet, vest, or whatever protective gear the Kevlar is fashioned to be.

Leo Fifield, a materials chemist at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Richland, Washington, said that Kevlar is "like a net catching a ball."

Moreover, Kevlar is lightweight and five times stronger than steel, according to DuPont, the company that manufactures it. It also has a lower density than carbon fiber, which makes it comfortable enough to wear, Fifield said.

"It needs to be effective, but then, the officer also needs to be willing to wear it," Fifield said. "It's not going to be effective at all if it's sitting on his desk."

However, although Kevlar is very difficult to pull apart — in other words, it has high tensile strength — it doesn't resist compression or squeezing, he said. That's why it's not used as a common construction material in buildings or bridges, Fifield said.

Still, Kevlar is used in other materials besides body armor, including spacesuits, city roads, fiber-optic cables, high-performance sporting goods and apparel, cellphones and mining belts, according to DuPont.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus