Real-Life 'Moby-Dick'? Testing Sperm Whales' Ramming Ability

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A vengeful whale rising up from the ocean's depths to wreck a boat with its massive head is a terrifying and enduring image from Herman Melville's classic novel "Moby-Dick" and, more recently, from the 2015 film "In the Heart of the Sea."

Based on an incident described in 1820 involving the Nantucket whaling vessel the Essex, the film relays the terrifying tale of an enraged sperm whale turning the tables on its tormenters, using its enormous head as a battering ram to smash a whaling ship to splinters. (The event also inspired "Moby-Dick" and the book "In the Heart of the Sea," published in 2000, from which the film was adapted.)

But was such a feat really possible? Were sperm whales truly the destructive powerhouses that whalers described? Recently, a team of engineers took a look at whether the unusual and oversize head of the sperm whale would be able to sustain the force required to demolish a whaling boat by ramming it. [Whale Album: Giants of the Deep]

Historical accounts

Sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) are the largest of the toothed whales. Males can grow to be up to 52 feet (16 meters) long, and the head alone can make up about one-third of that length. They can weigh as much as 45 tons (41 metric tons).

The New Bedford Whaling Museum in Massachusetts describes four "famous" incidents of sperm whales allegedly attacking whaling ships. During these confrontations, all of which were said to have occurred between 1820 and 1902, the whalers reported that the whales repeatedly rammed the ships with their heads until the vessels were destroyed. The first mate of the Essex, Owen Chase, fancifully described a whale bearing down upon the ship "with vengeance in his aspect."

But while there's no question that sperm-whale heads are big and heavy, could they have generated enough force in a ramming attack to utterly destroy a structure like a whaling boat that weighed up to 238 tons (216 metric tons), or four to five times the whale's weight?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Given that sperm whales' heads house sensitive acoustic structures that could be damaged by ramming, the researchers knew that they would need to test the resilience of those organs as well. [Incredible Video: Curious Whale Inspects Underwater Robot]

Junk science

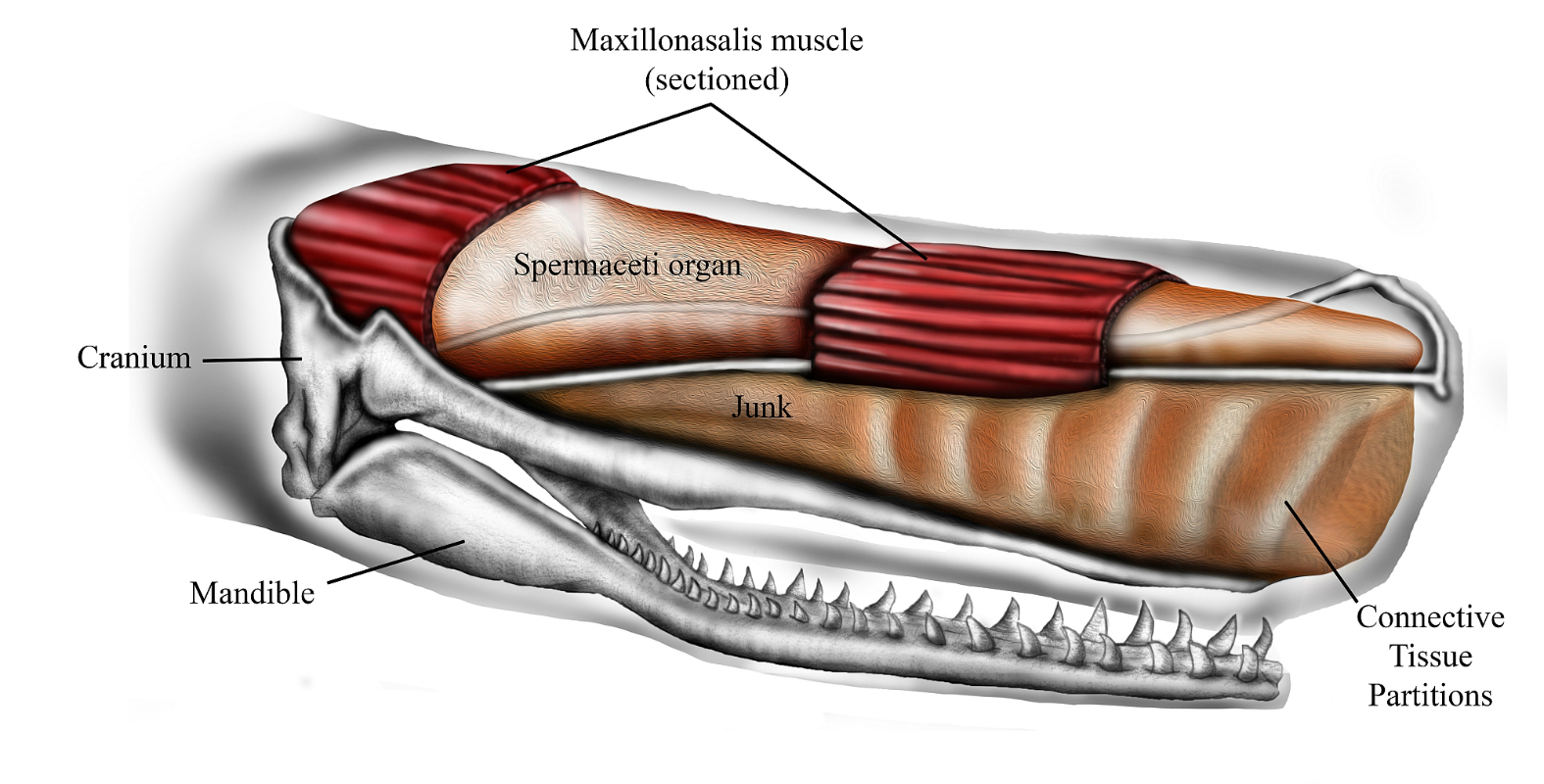

Using computer simulations and working from published data on sperm-whale tissue and skeletal structure, the scientists modeled impacts of varying types, and from a range of directions. Then, they evaluated how force was absorbed and dispersed by the two large, oil-filled sacs stacked on top of each other inside a sperm whale's head: the sound-generating spermaceti organ on top, and the "junk" — mostly connective tissue, which also plays a part in echolocation — on the bottom.

The whale's junk proved to play a vital role, the scientists found, with tissue partitions distributing much of the stress from ramming impacts and thereby preventing the skull from fracturing.

While ramming behavior is common in some animal species, used as a form of competition between males, it has been observed only once in sperm whales, the researchers reported. But their findings suggest that this behavior could be more common in sperm whales than was previously suspected, and that whalers' accounts of the devastation wrought by living, battering rams may not be such tall tales after all.

The findings were published online today (April 5) in the journal PeerJ.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus