Anglo-Saxon Island Discovered in England

A newly discovered Anglo-Saxon settlement in England is surrounded by dry land today, but once was an island oasis amidst marshland. And at least some of its inhabitants were literate.

The long-ago island was inhabited continuously between at least A.D. 680 and A.D. 850, during the Middle Anglo-Saxon era, archaeologists from the University of Sheffield report in the April 2016 issue of Current Archaeology. Among the tantalizing discoveries in the area were 16 silver styluses for writing and a tablet inscribed with the female name "Cudberg" — perhaps a coffin plaque for a long-ago resident.

The site is in Lincolnshire parish near the village of Little Carlton, an area of grassy fields, marshes and small forests. The first hint that something intriguing might be buried in this bucolic setting came in 2011, when a metal detector hobbyist named Graham Vickers discovered a silver writing stylus featuring decorative carvings. Archaeologists dated the utensil to the eighth century. [See Photos of the Newfound Island Site and Its Treasures]

Additional searches near the ground surface turned up more treasures: loom weights, whetstones, glass fragments and pottery pieces. One little glass piece was crisscrossed with decorative, intertwined glass strands. These finds hint at a settlement with access to life's little luxuries.

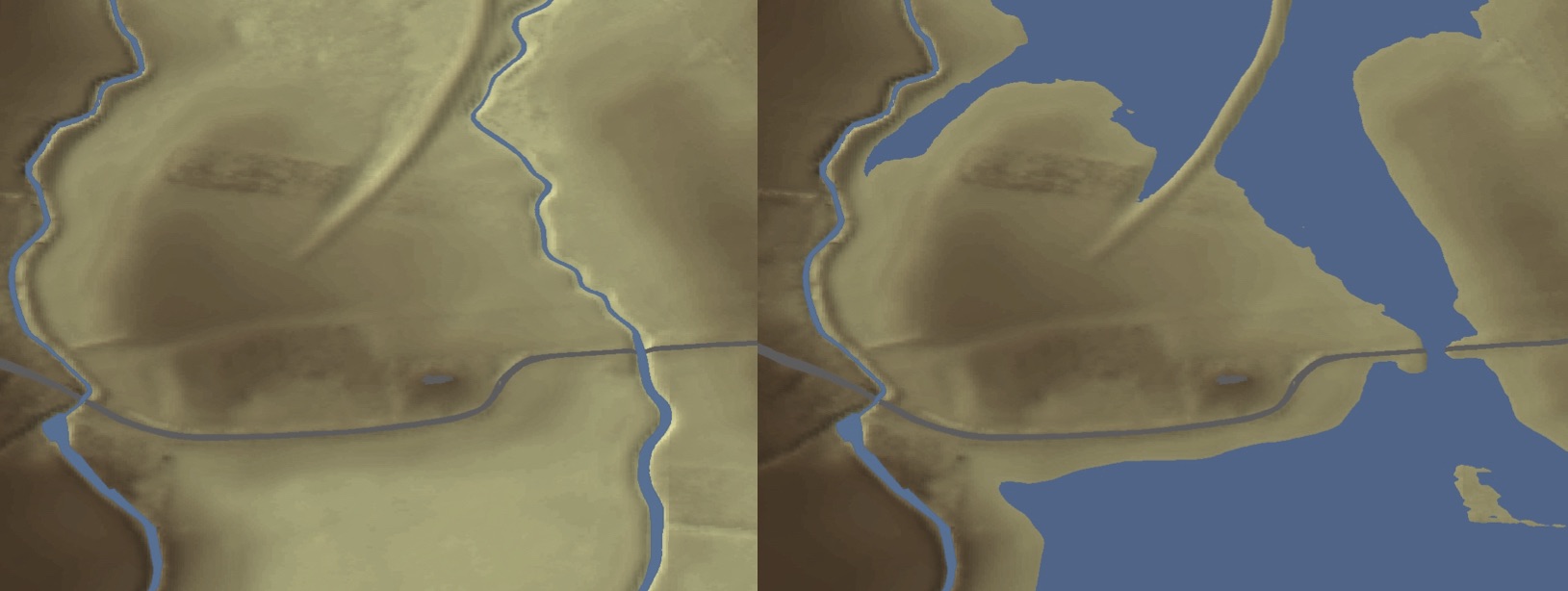

The flow of artifacts from the site caught the attention of University of Sheffield archaeologist Hugh Willmott and doctoral student Pete Townend, who conducted geophysical surveys and Lidar scans of the area. Lidar uses laser pulses to measure and map out surface features. The data can be used to create models that show the shape of the Earth with all its vegetation stripped away.

These surveys revealed a slight rise in the land around the area richest in artifacts. As the archaeologists moved south, where fewer artifacts were found, they noticed that the land dipped. A survey of the historical field names of the area turned up monikers like "Little Fen," suggesting a marshy history. All of this data added up to a picture of the site as a long-ago island in a marsh, which has since been drained and converted into agricultural fields.

On this island, people cooked, butchered animals, smelted metals and read and wrote, the researchers discovered after digging nine exploratory trenches. The dig turned up medieval ditches full of trash (pottery pieces, butchered animal bone) and signs of building foundations (post holes and man-made gullies). The archaeologists found a built-up bank reinforced with wooden posts that would have been the medieval version of flood control; they also found the base of a 4-foot-wide (1.2 meters) hearth that was used to smelt metal, as melted bits of lead nearby revealed. The hearth was on the outskirts of the settlement, likely because it would have been noisy and smelly, the researchers wrote.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The archaeologists also found signs of domestic life, including dress pins made from copper and tweezers. They even found a small Anglo-Saxon coin called a sceat, stamped with a human face and dating back to between A.D. 725 and A.D. 745.

Researchers aren't sure what the site was used for. It could have been a trading post, or a monastic center, where monks used silver styluses to copy out texts. Nor are they sure why the settlement eventually faded away, though the youngest artifacts date back to the late 800s — a time when the Vikings began to push into the region. Whether a Viking invasion spelled the end for this settlement remains a mystery, however.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus