Cases of Gastroschisis, a Birth Defect, on the Rise in the US

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Cases of a rare birth defect called gastroschisis are increasing in the U.S., according to a recent government report. But what is gastroschisis, and what causes it?

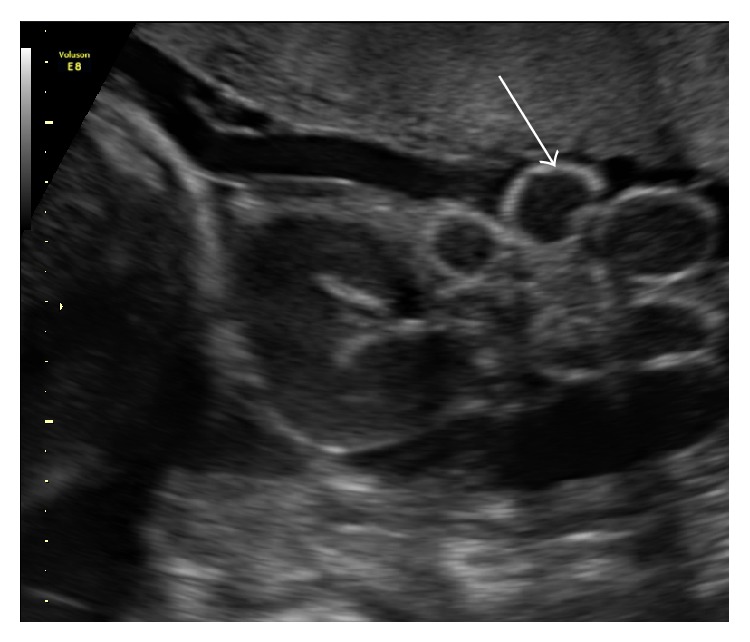

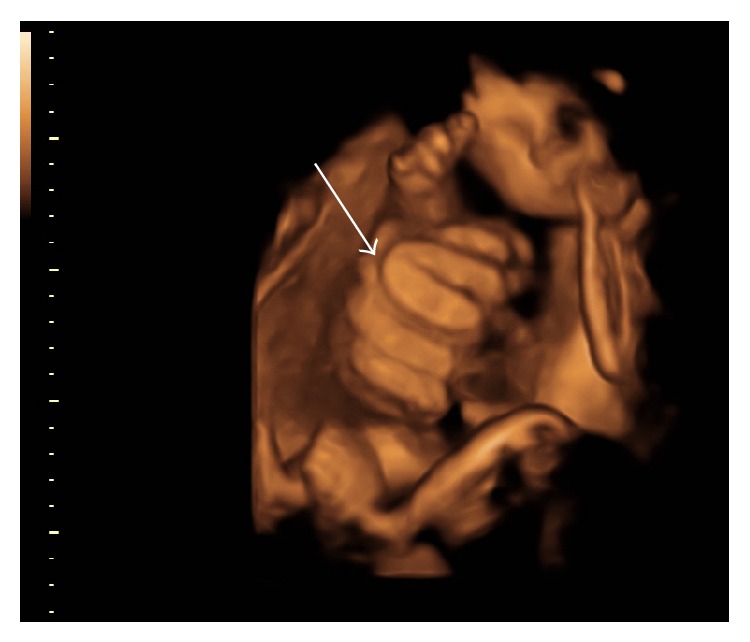

Gastroschisis (GAS-tro-SKEE-sis) occurs when the muscles in the intestinal wall of a fetus do not develop properly, thus causing the intestines to poke through an opening in the skin, to the right of the umbilical cord.

In some cases, other organs, like the stomach, may also develop outside the baby's body, said Dr. Holly Hedrick, an attending pediatric and fetal surgeon at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. [9 Uncommon Conditions That Pregnancy May Bring]

"It's typically diagnosed during the second trimester by ultrasound," Hedrick told Live Science. During the first trimester, the fetus's intestines aren't in a fixed position inside the body — they "come out and go back in," making it difficult for a doctor to tell if something's wrong, Hedrick said.

By the second trimester, intestines should be permanently inside the fetus, and if they're not, intestine loops that are visible on an ultrasound point to the gastroschisis abnormality, she said.

In a recent report, researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that yearly cases of gastroschisis in the U.S. more than doubled, rising 129 percent, between 1995 and 2012. The increase is concerning, but the condition remains rare — there are now about 2,000 babies in the U.S. born yearly with gastroschisis, the report said.

A previous report showed that gastroschisis cases in the U.S. doubled between 1995 and 2005 —from about 2 cases per 10,000 live births to about 4 cases per 10,000 live births, according to findings published in 2013 in the journal Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new report shows that the biggest increase in the rate of gastroschisis has been in babies born to younger, non-Hispanic black women, age 20 or under, the CDC said. The report analyzed data from 14 states, representing about 29 percent of all births in the U.S.

Hedrick, who was not involved with the CDC study, told Live Science that babies born with gastroschisis generally need surgery shortly after birth to move the displaced organs back inside the body and to repair the wall meant to hold them in place. But the severity of the harm to a baby from having the exposed intestines can vary widely, Hedrick said.

"The outcome of the baby is directly related to the function of the bowel," Hedrick told Live Science. If the intestine is exposed during pregnancy, it can be damaged — by exposure to the amniotic fluid surrounding it, or by trauma from repeated contact in the womb — and this damage can continue to affect the baby's health, even after corrective surgery.

In about 10 percent of gastroschisis cases, only a small part of the bowel is exposed, and replacing it is relatively simple: "You can just return the bowel to the abdominal cavity without surgery," Hedrick said, adding that hospital stays for these cases typically last less than one month.

But in some cases, if the blood supply to the intestines is restricted and the intestine becomes malformed, or if there's extensive scarring to the intestinal tissue, the return of normal bowel function can be delayed severely, Hedrick said. About 20 percent of gastroschisis cases exhibit these extreme complications, which can require hospital stays lasting three to six months and multiple surgeries, and can leave the baby with developmental problems caused by an impaired ability to absorb nutrients. In some cases, the damage is too great for the baby to survive, Hedrick said.

Most gastroschisis cases fall somewhere between these two extremes, Hedrick told Live Science. Typically, doctors replace the exposed bowels using a specialized pouch called a "silo," which stacks the intestines and uses a combination of gravity and pressure to gradually push them back into place, Hedrick explained. Once the intestines are tucked away, the abdominal wall is closed, and the babies are usually released from the hospital after three to six weeks, once doctors can tell that their intestines are working well.

Health officials are not sure what causes gastroschisis, though the CDC suggests that it might be triggered by genetic factors — either independently or in combination with other influences like environmental conditions that the mother is exposed to, or food, drink or medicines she ingests while pregnant.

However, the CDC researchers noted a particularly dramatic uptick in the number of infants with gastroschisis born to young, black mothers. Over an 18-year period, gastroschisis cases among this group more than tripled, rising 263 percent. In comparison, there was a 68 percent increase in infants with gastroschisis born to white mothers over the same period.

The CDC's analysis gives a clearer picture of where the birth defect is happening, but many questions still remain about what causes the deformity, why teen mothers are especially susceptible, and why the condition seems to be occurring more frequently than ever in children born to black women.

"It concerns us that we don't know why more babies are being born with this serious birth defect," Coleen Boyle, director of the CDC's National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, said in a statement.

Abbey Jones, lead author of the CDC report and an epidemiologist for the CDC's National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, told Live Science that further steps are required not only to determine why the risks are greater for young mothers, but also to uncover an explanation for the escalating number of cases.

"As the cause of the increase in prevalence is unknown, public health research on gastroschisis is urgently needed," Jones said.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus