Sorry, Spider-Man! You're Too Big to Scale That Wall

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

If the superhero Spider-Man were to climb walls like a true spider, he would need ridiculously enormous feet, a new study finds.

Like spiders, a variety of critters can scurry up walls, including some species of cockroach, lizard and beetle. But there's a reason why geckos are the largest animals that can scale walls this way: larger and heavier animals would need titanic-size sticky footpads to ascend tall buildings, the researchers said.

"If a human, for example, wanted to walk up a wall the way a gecko does, we'd need impractically large, sticky feet — our shoes would need to be a European size 145 or a U.S. size 114," study senior author Walter Federle, a professor in the Department of Zoology at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, said in a statement. [Biomimicry: 7 Clever Technologies Inspired by Nature]

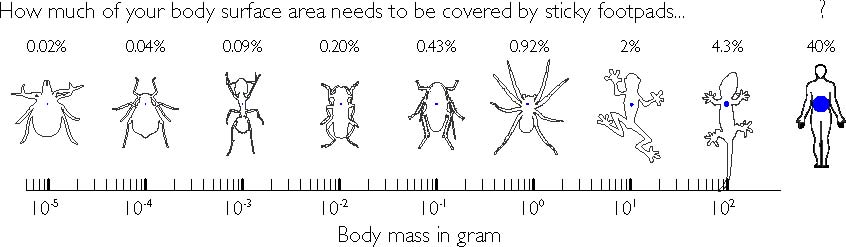

Sorry, Spider-Man — the man holding the record for world's largest feet has a U.S. shoe size of 26, according to Guinness World Records, meaning you've got a ways to go. In fact, humans would need adhesive pads covering 40 percent of their body, or about 80 percent of their front, in order to climb up a vertical wall, the researchers said.

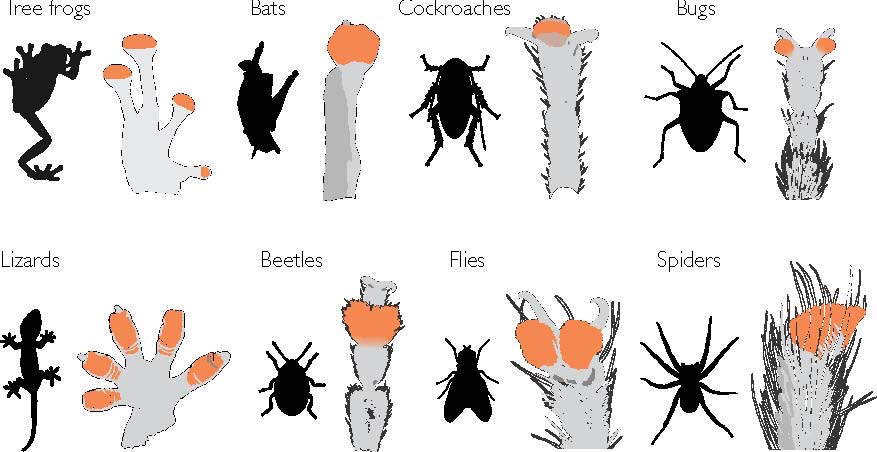

To investigate this sticky phenomenon, the researchers examined the weight and footpad size of 225 species of climbing animal. They found that larger animals with "sticky" feet, such as geckos, have larger adhesive footpads than their smaller, sticky-feet peers, such as mites and spiders. (This "stickiness" is actually a van der Waals force, in which electrons on the animal and the wall interact, creating an electromagnetic attraction, at least in geckos.)

Moreover, the different animals had "remarkably similar footpads" said study first author David Labonte, a doctoral student in the Department of Zoology at the University of Cambridge.

"Adhesive pads of climbing animals are a prime example of convergent evolution — where multiple species have independently, through very different evolutionary histories, arrived at the same solution to a problem," Labonte said. "When this happens, it's a clear sign that it must be a very good solution."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But, there is a limit to how large an animal can grow before its adhesive pads would need to be so large that they would become impractical, the researchers said. This insight could help scientists understand the implications of designing bio-inspired adhesives, they added.

Sticky solution

But nature has presented another solution for vertical climbing. Some species, such as frogs, simply use stickier footpads.

"We noticed that within closely related species, pad size was not increasing fast enough to match body size, probably a result of evolutionary constraints," said study co-author Christofer Clemente, a lecturer who studies animal form and function at the University of the Sunshine Coast in Australia. "Yet these animals can still stick to walls."

Clemente noted, "within frogs, we found that they have switched to this second option of making pads stickier rather than bigger. It's remarkable that we see two different evolutionary solutions to the problem of getting big and sticking to walls."

But even without adhesive pads, larger animals are still able to get around. For instance, many have developed claws and toes that help them climb, the researchers said.

The study was published online yesterday (Jan. 18) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus