T. Rex Gets Weighed

Imagining dinosaurs in the flesh is tricky since the prehistoric subjects died out some 65 million years ago, but a new tool is helping to fill out the skeleton of T. rex and one of the largest-known duckbill dinosaurs, among other beasts.

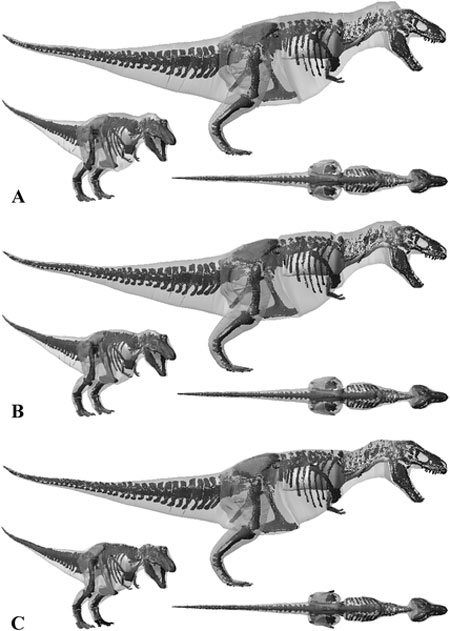

Paleontologists used laser imaging technology called LiDAR for the first time to create 3-D computer models of five dinosaurs, including two of Tyrannosaurus rex , a spiny predator called Acrocanthosaurus atokensis, the ostrich-like Strutiomimum sedens and the plant-eating Edmontosaurus annectens, a hadrosaur or duckbill dinosaur.

"Our technique allows people to see and decide for themselves how fat or thin the dinosaurs might have been in life," said Karl Bates, a biomechanics researcher at the University of Manchester in the U.K. "You can see the skeleton with a belly. Anyone from a 5-year-old to a professor can see it and say, 'I think this reconstruction is too fat or too thin.'"

LiDAR has found use in everything from police radar guns to satellite mapping, as well as NASA's Phoenix Mars Lander. Researchers used the technology in this case to scan full mounted dinosaur skeletons, and then digitally reconstruct the body cavity and internal organs such as stomach, lungs and air sac around the 3-D skeleton model.

Having the models allowed the team to change weight estimates and see the possible range of dinosaur fitness. Lower weight estimates probably made the most sense for dinosaurs, because weight affected speed, energy use and demands on the respiratory system.

The larger T. rex specimen at the Manchester Museum in the U.K. may have weighed almost 9 tons, or about as much as the largest African elephant. The smaller T. rex from the Museum of the Rockies in Montana could have weighed anywhere between 6 and 7.7 tons.

"Dinosaurs probably had about 30 percent of their mass in their hind limbs, with the plausible range somewhere between 20 to 40 percent," Bates told LiveScience. "It has been shown in previous studies that giants like T. rex would have needed much more muscle than this in their hind limbs to be the kind of fast runners that are sometimes portrayed as in the media (e.g. Jurassic Park)."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Acrocanthosaurus atokensis would have looked like the younger and wilder cousin to T. rex, boasting large spines on its back and roaming the Earth in the mid-Cretaceous period, around 110 million years ago. Its specimen from the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences roughly matched the mass of the smaller T. rex.

The Strutiomimum sedens from the Black Hills Institute of Geological Research in South Dakota weighed somewhere between 882 to 1,323 pounds as a relative lightweight whose name means "ostrich mimic." Incidentally, Bates and his colleagues calibrated the accuracy of their laser imaging by using a modern-day ostrich.

Edmontosaurus annectens hailed from the duck-billed hadrosaur family. The juvenile specimen on hand from the Black Hills Institute weighed in at roughly 2,000 pounds, although it may have matched T. rex for size when fully grown for its own protection.

Bates and colleagues next plan to use their mass estimates to try and figure out dinosaur movement and walking style. Their latest research was detailed last week in the journal PLoS ONE.

"Reconstructing more dinosaurs in such detail will allow us to examine changes in body mass and particularly center of mass as they evolved," said Bates. "As we know, dinosaurs evolved into birds. As they did so, the center of mass moved forward and different walking styles evolved."

- A Brief History of Dinosaurs

- Avian Ancestors: Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly

- Images: Dinosaur Fossils