Malaysian Airlines Mystery: What Newfound Wing Debris Could Reveal

Update, August 5, 2:23 PM ET: Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak said on Wednesday, August 5, that the wing debris did come from Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, which disappeared on March 8, 2014.

The high-profile disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370 remains a mystery — but the recent discovery of a possible wing part points to an ocean landing, raising hopes for a resolution.

"It would be unusual to have only one piece of an airplane floating around on the surface. There must be other pieces out there," said David Gallo, the director of special projects at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts.

The piece, possibly from the wing of the Malaysia Airlines plane that disappeared almost 500 days ago, made its way to the shores of RéunionIsland, a French island in the Indian Ocean that lies east of Madagascar. [Flight 370: Photos of the Search for Missing Malaysian Plane]

The part, called a flaperon, attaches to the backside of a jetliner's wing and expands and contracts during takeoff and landing. The flaperon recovery spurred an anxious search on RéunionIsland for more debris, but aside from some false leads, including a report of a domestic aircraft ladder, no other parts have yet been identified, according to officials.

The flaperon, identified as one from the wing of a Boeing 777-200 – the same plane as MH370, spotted on July 29, was found more than 2,000 miles (3,219 kilometers) from where the initial search for the doomed MH370 flight occurred in the Indian Ocean. But researchers can map currents and other ocean processes to trace the debris' path back to its origin — possibly turning up even more wreckage. Biology has a role as well, as scientists can look at organisms growing on the metal piece to narrow down their search.

Indian Ocean

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The missing plane departed Kuala Lumpur International Airport in Malaysia on March 8, 2014, for Beijing, but never arrived. The search force, which included officials from Malaysia, Australia and France, has taken the form of a "CSI Oceanic" series, Gallo said, with the "crime scene" spanning thousands of miles of the Indian Ocean and evidence being tampered with by the wind, currents and ocean circulation.

"The ocean does a great job of dispersing things," Gallo told Live Science.

And it's a big place: Although the Indian Ocean is the smallest of the world's oceans, it still extends 5,965 miles (9,600 km) from Antarctica to the inner Bay of Bengal. It spans 4,847 miles (7,800 km) from east to west, between southern Africa and Western Australia.

Investigators can use computer models to simulate how debris moves in the ocean using ocean current data and possible crash sites. Without knowledge of the initial crash site, the process is trickier and lengthier, but still possible. [What Happened to Malaysia Flight MH370? 5 Likeliest Possibilities]

The aircraft likely went down off Australia, though it's difficult to say how far out, said airline recovery expert Steve Saint Amour, the COO of Eclipse Group, which runs marine operations out of Annapolis, Maryland.

Ocean circulation is driven by winds, including monsoon winds, which can influence the journey the plane debris followed, said Luca Centurioni, an associate researcher at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego. Although the wind can push objects around, their various shapes and sizes also contribute to where they end up.

Debris moves according to what the ocean currents, waves and wind are doing at that location, Centurioni said. "If you have a big chunk of the debris sticking out of the water," the wind would be the primary force on it rather than another mostly submerged object, which would be at the mercy of ocean currents driven by the temperature and density of the seawater. Massive waves can also rise out of the ocean to pound and reroute debris.

"So you have at least three different factors pushing the debris, and all of them can go in a different direction," Centurioni said. "The end result is almost something which is impossible to track, especially after so many days have passed."

Immense search space

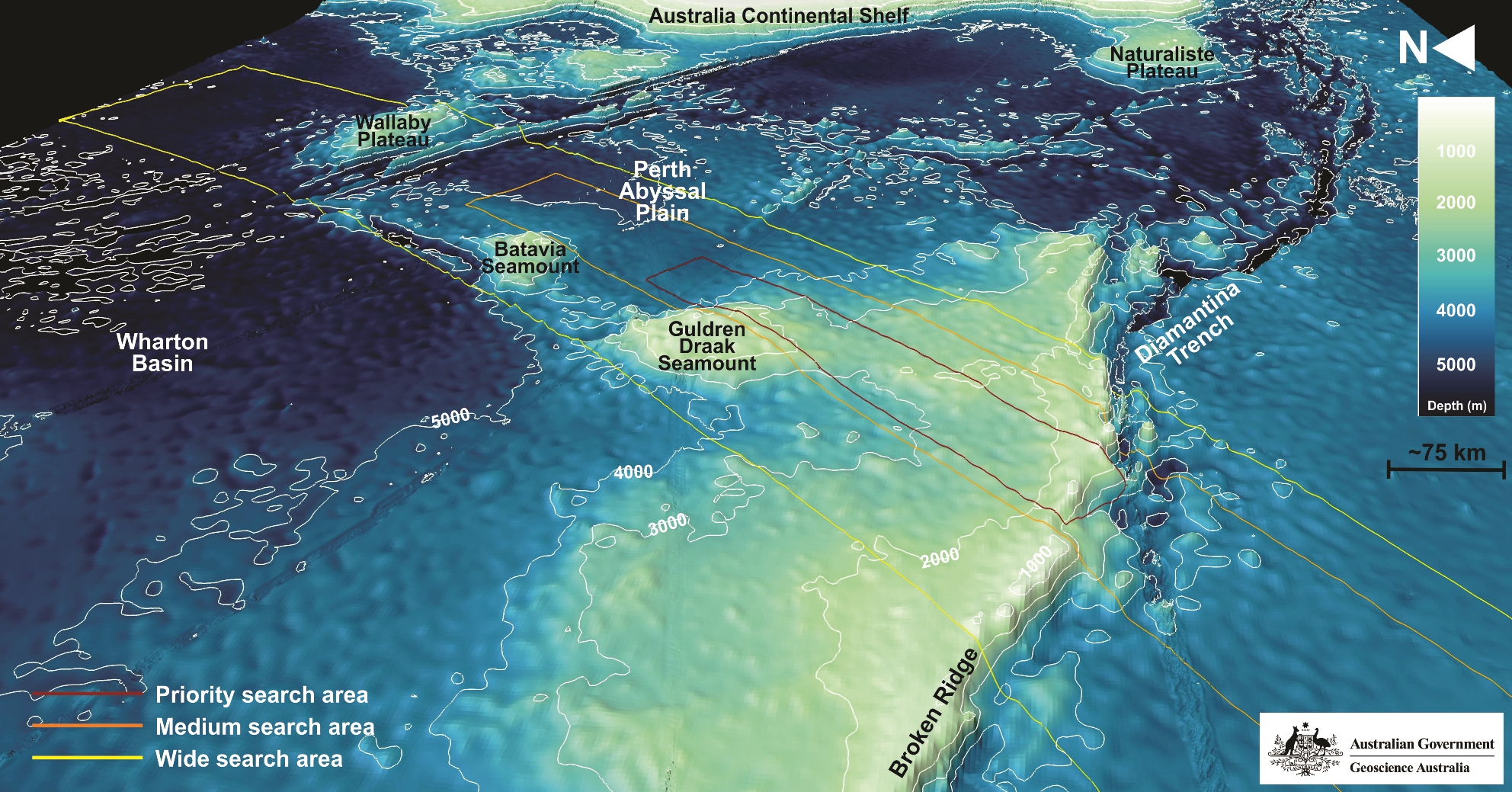

Although there are instruments in the Indian Ocean that measure the currents and how they're affected by monsoons, the level of detail isn't precise enough to track a piece of an airplane like the flaperon, Gallo said. The entire search area, which covers 2.24 million square nautical miles (7.68 million square km), could fit 1.98 billion Boeing 777-200s inside, according to The Guardian.

The search for the missing plane covers an area that looks like a "long ribbon of deep water" rather than "a bull's-eye or haystack," Gallo said. It's a "very strange kind of search area."

Furthermore, the debris could sink if it lacks air pockets and fills with water, or if there is a lot of barnacle, algae or other vegetation growth on it that weighs it down, Centurioni told Live Science.

The Indian Ocean floor is marked by the steep and rugged Southwest Indian Ridge, where the northern African and southern Antarctic plates move away from each other, and the relatively smooth and flat Southeast Indian Ridge, where the northern Indo-Australian plate moves away from the southern Antarctic plate.

The ridges and their volcanoes, along with underwater cliffs and valleys, provide ample room for sinking debris to hide, Gallo said. To reach the depths of the ocean and find the plane's black box (thought to be on the ocean floor), researchers used camera-equipped remotely operated vehicles tethered by a cable and controlled like a video game from the ocean's surface. They have yet to locate this black box, which contains vital information about the plane's descent and could indicate how to locate plane debris.

Autonomous underwater vehicles can also aid deep-water searches and are launched by a ship. Lastly, towed array sonars can hang from a cable off the back of a ship and map the topography of the seafloor. The different instruments have pros and cons — for more precise work in treacherous terrain, ROVs are more often used, but for vast surveys, AUVs or towed array sonars are preferred.

Investigators have used are currently using all three instruments to aid their search.

If the recently discovered flaperon is from the missing Malaysian Airlines jet, modelers can use its location to retroactively model the path the part took, Gallo said. "And then people will be looking at what's growing on that piece of airplane — barnacles and the like — and what chemical residue is on the piece of airplane," Gallo continued.

Professors at the University of Cologne in Germany identified the barnacles on the discovered flaperon as goose barnacles, which are limited to certain climate zones. Determining the species of goose barnacle can indicate if the crash occurred in cooler or warmer waters.

The discovered flaperon isn't a surprising find, Amour told Live Science. However, without other pieces of wreckage, little can be inferred about what happened to the plane.

Previous plane disappearance

Investigators had an easier time locating debris from the Air France jetliner that crashed in 2009 on its way from Rio de Janeiro to Paris. Debris from the flight floating on the surface of the water was spotted within a week of the crash, Gallo said.

"We went pretty much right beneath the last known position and there the plane was," said Gallo, who was involved in the search for the Air France jet. In the case of MH370, "the plane simple vanished."

The search for parts from the Malaysian plane is about to exceed 500 days, frustrating families of lost passengers and investigators who are funding what has become the costliest commercial airline jet search in history, Gallo said. "This new piece shows up, probably just in time," he added.

Elizabeth Goldbaum is on Twitter. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science