BRAIN Initiative Update: Q&A with Neuroscientist Cornelia Bargmann

In 2013, President Barack Obama launched an ambitious research effort to revolutionize understanding of the human brain. Known as the BRAIN Initiative (Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies), the project aims to develop new tools to map brain activity, which could ultimately lead to new ways to treat, prevent and cure brain disorders.

Cornelia "Cori" Bargmann has been one of the architects of this bold science effort, whose members include scientists from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and other public and private organizations. A neuroscientist at The Rockefeller University in New York City, Bargmann was one of the co-chairs of the BRAIN Initiative working group, which developed a detailed plan for the project that was released in June 2014.

Bargmann spoke with Live Science about the initiative's progress, what the project can learn from other grand challenges and the promise and ethics of new brain technologies. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain]

You can read an edited transcript of the conversation below.

Live Science: Since the BRAIN Initiative was launched in April 2013, what has it achieved so far?

Cori Bargmann: I would say that the most important thing that's happened in the BRAIN Initiative over the past [year and 8 months] has been the fact that a lot of new people have joined it. Not just conventional neuroscientists, but also medical experts and technologists from chemistry and physics and engineering.

At a more practical level, the idea of the BRAIN Initiative has been broken down and developed to turn it into a series of concrete goals. The first grants based on those goals have been funded. In a joint meeting at the White House, you could just feel the energy in the room of how excited people were about what they were doing. The proposals were imaginative, original and outside the box.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science: Why now?

Bargmann: Recent advances in technology make it seem as though it will be possible to address this problem. But it can't be addressed by just proceeding the way we're doing now — one step at a time, with everyone [taking] their own separate approach.

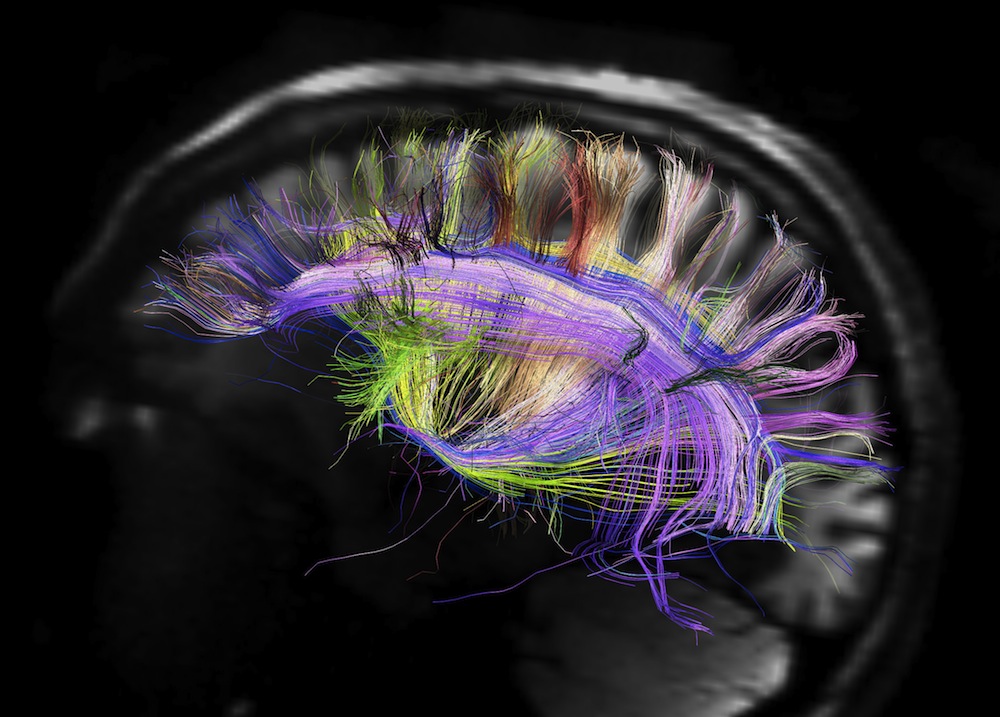

What is the pattern of activity that sweeps through the brain every time you perceive something, or feel an emotion or remember that you have to buy groceries after work? All these things are produced in the brain by patterns of electrical and chemical activity, transmitted rapidly by thousands of millions of nerve cells.

Traditionally, people have studied the brain and learned an enormous amount by studying neurons one at a time. But neurons don't act as individuals; they act as circuits and networks. We know we need to record signals from large numbers of neurons, but we don't know how large that number needs to be. That's one of the questions the BRAIN Initiative is hoping to answer.

Live Science: What are some of the most exciting technologies being developed?

In 2013, one of the people involved in planning the BRAIN Initiative with me, Mark Schnitzer of Stanford University, recorded the activity of 1,000 neurons in the hippocampus, the site at which new memories form, for a month [in a mouse brain]. And the [Dec. 17, 2014] issue of the journal Neuron includes a paper about electrical methods for recording hundreds of neurons in animals that are completely freely moving, wirelessly.

Neuroscience has traditionally been a science in which people observed the activity of the brain but couldn't perturb it. But that potential has grown up in the past 10 years in optogenetics, a technique that allows scientists to stimulate neurons of interest by pointing light toward them and making them active or inactive. For example, by activating neurons in a part of the brain involved in fear, you can cause animals to show behavior as though they had experienced a frightening stimulus.

Live Science: Should we have any ethical concerns about being able to manipulate the brain?

Bargmann: If behavior and cognition and our sense of self emerges from the brain — as we think it does — when you start to change the activity of the brain, you have the potential of interfering with what makes a person human and unique.

Unfortunately, for the past 50 years, we have already had methods that can, in a major way, interfere with the function of human brains. A troubling one is the use of lobotomies to make patients easier to handle. The bad news is, they were insidious and wrong. The good news is, we recognize they were wrong.

There will be ethical issues that come up in context with any scientific knowledge, especially in the brain, which we will have to [handle] with sensitivity and intelligence. There are a lot of people suffering because their brains are not functioning properly, and those people would potentially benefit [from interventions].

When the president announced the BRAIN Initiative, he simultaneously announced the creation of a bioethics committee. They released their first report before the research was even funded.

Live Science: What can the BRAIN Initiative learn from other grand challenges, such as the Human Genome Project or the War on Cancer?

Bargmann: I think the BRAIN Initiative is the "war on ignorance." People sometimes say the War on Cancer failed. I 100 percent do not believe that. It's still going on. I cloned the Herceptin gene for breast cancer [in rats] as a graduate student in 1986. A therapy didn't emerge until 1998 — that's how long these things take. There's no quick fix.

The Human Genome Project was very well planned, and very successful as a scientific venture. Another good lesson is to share all the data — including tools and methods. One cautionary lesson from the Human Genome Project is, don't raise false hopes. There was a sense that once the genome was there, we would understand everything and medical breakthroughs would come tumbling out. It wasn't like that.

Let's promise 10 years of science, and then 10 years of medicine. Let's not promise we're going to solve Alzheimer's.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus