Photos: Strange, Eyeless Creatures from the Cambrian Period

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Fossils of bizarre, figure-8 shaped creatures called vetulicolians that lived during the Cambrian Period have now been discovered. An analysis of the fossils revealed these eyeless creatures sported a hollow nerve structure called a notochord similar to today's vertebrates, including humans. Here's a look at the oddballs. [Read full story on the bizarre Cambrian creature]

Off Kangaroo Island

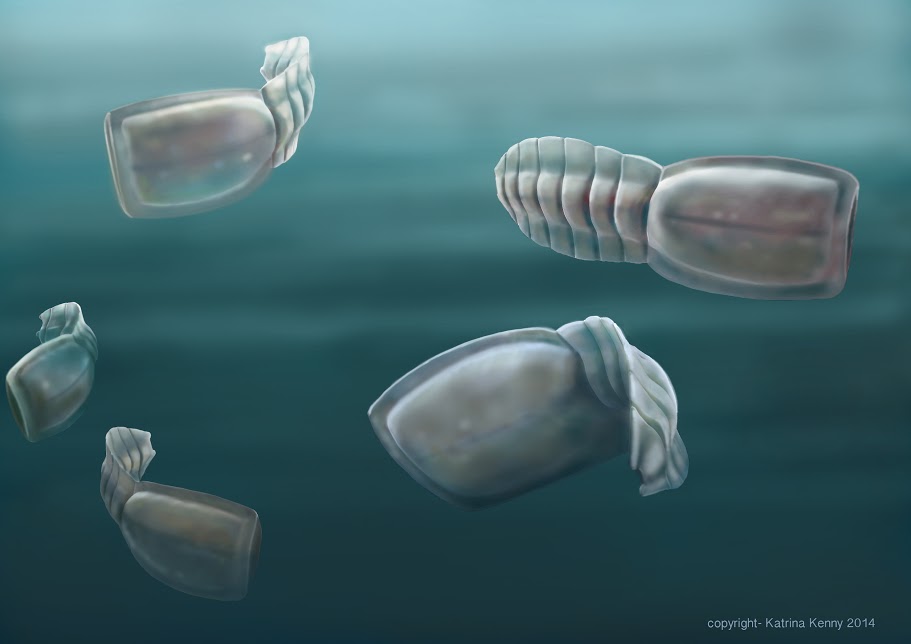

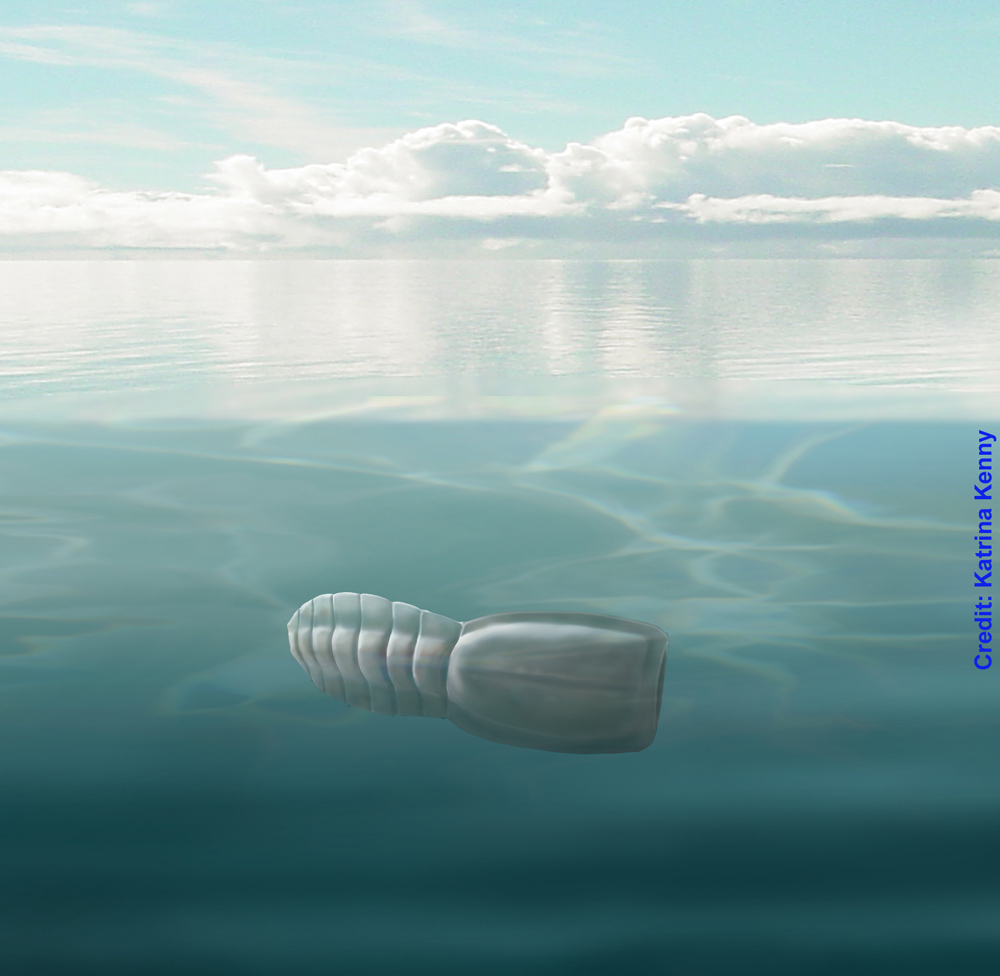

The 500-million-year-old swimming filter-feeders called vetulicolians have been a mystery since their discovery more than a century ago. Now, with the discovery of new vetulicolian fossils on Kangaroo Island off of Australia, researchers at the University and Adelaide and the South Australian Museum believe they understand how vetulicolians fit into the tree of life. As improbable as it seems, these bizarre creatures are distant relations of humans. (Credit: Copyright Katrina Kenny, 2014)

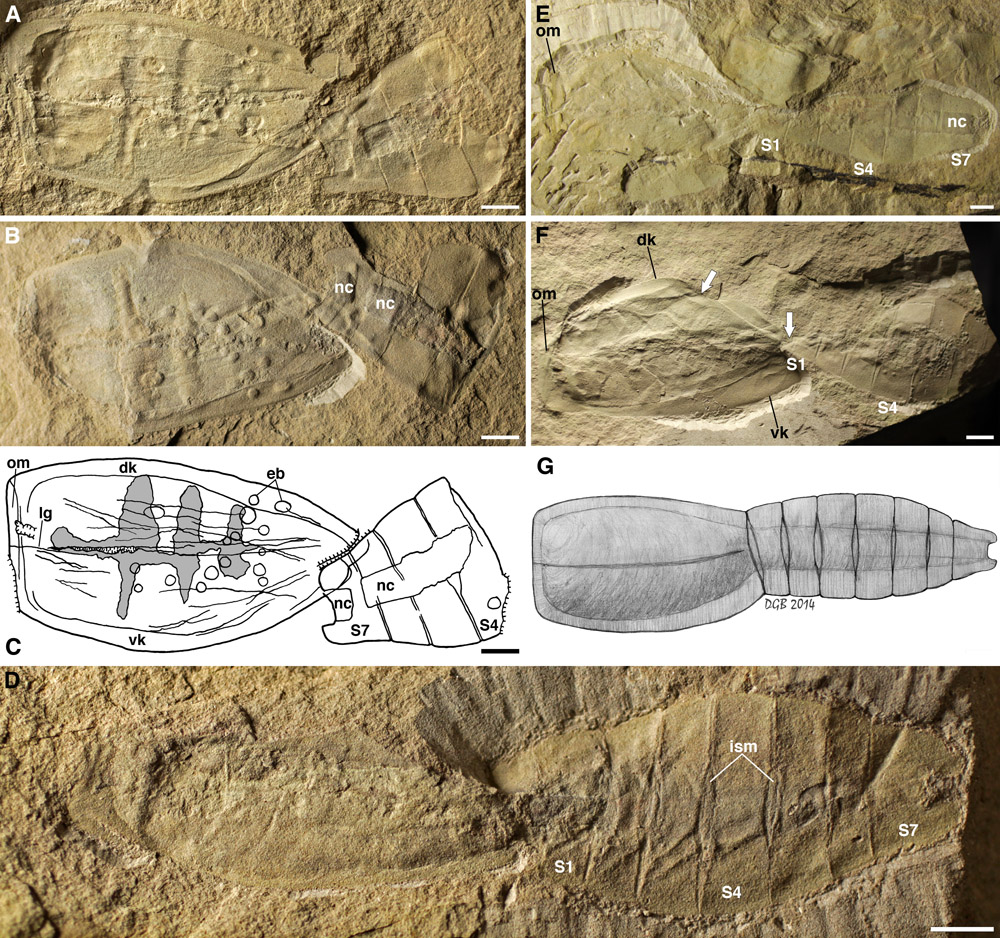

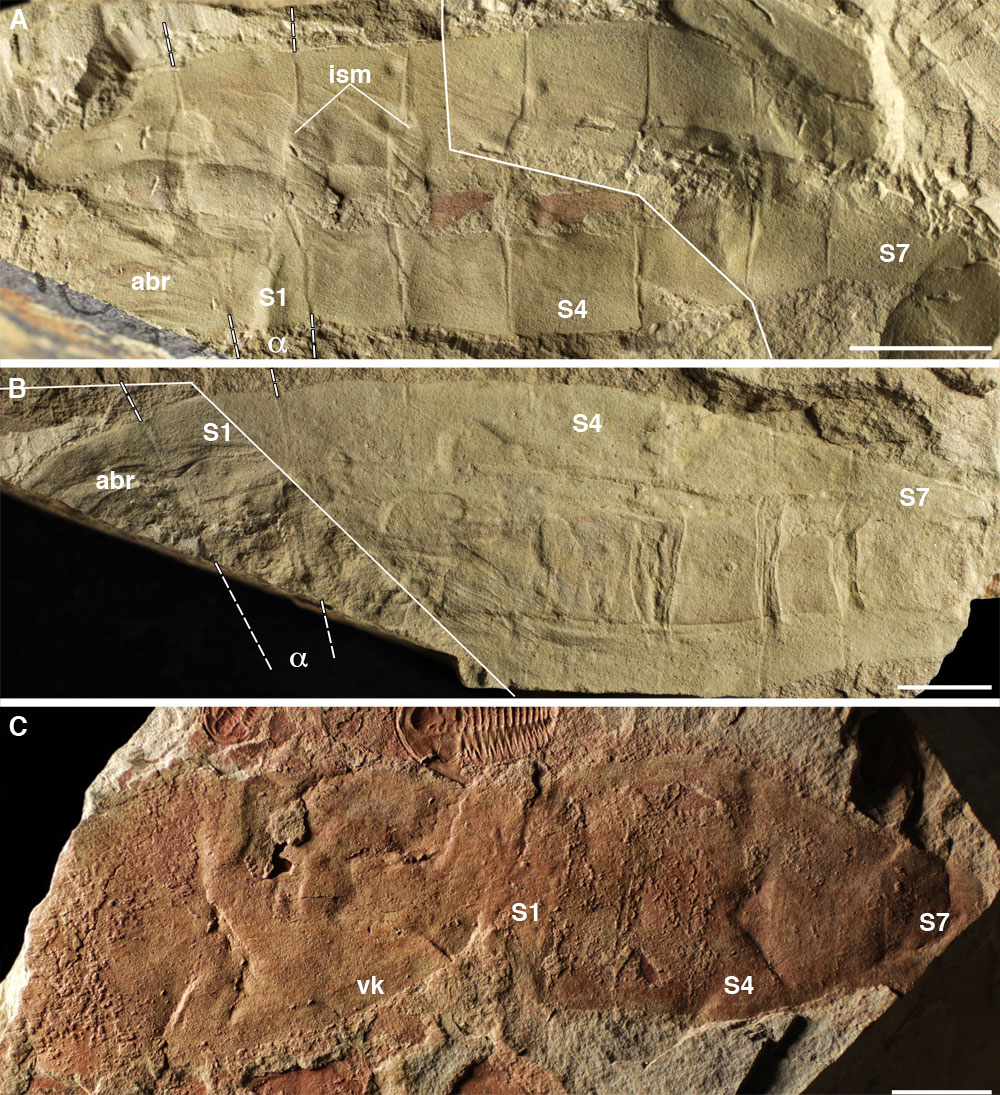

A large specimen

The distinct figure-8 shaped fossil of a vetulicolian, dating back 500 million years. The largest of these fossils measures about 4.9 inches (12.5 centimeters) in length. New vetulicolian fossils found on Kangaroo Island reveal a rod-like structure in the tail, similar to a backbone. This discovery reveals that vetulicolians are relatives of vertebrates, or animals with backbones, placing them in a distant relationship with modern humans. (Credit: University of Adelaide/South Australian Museum)

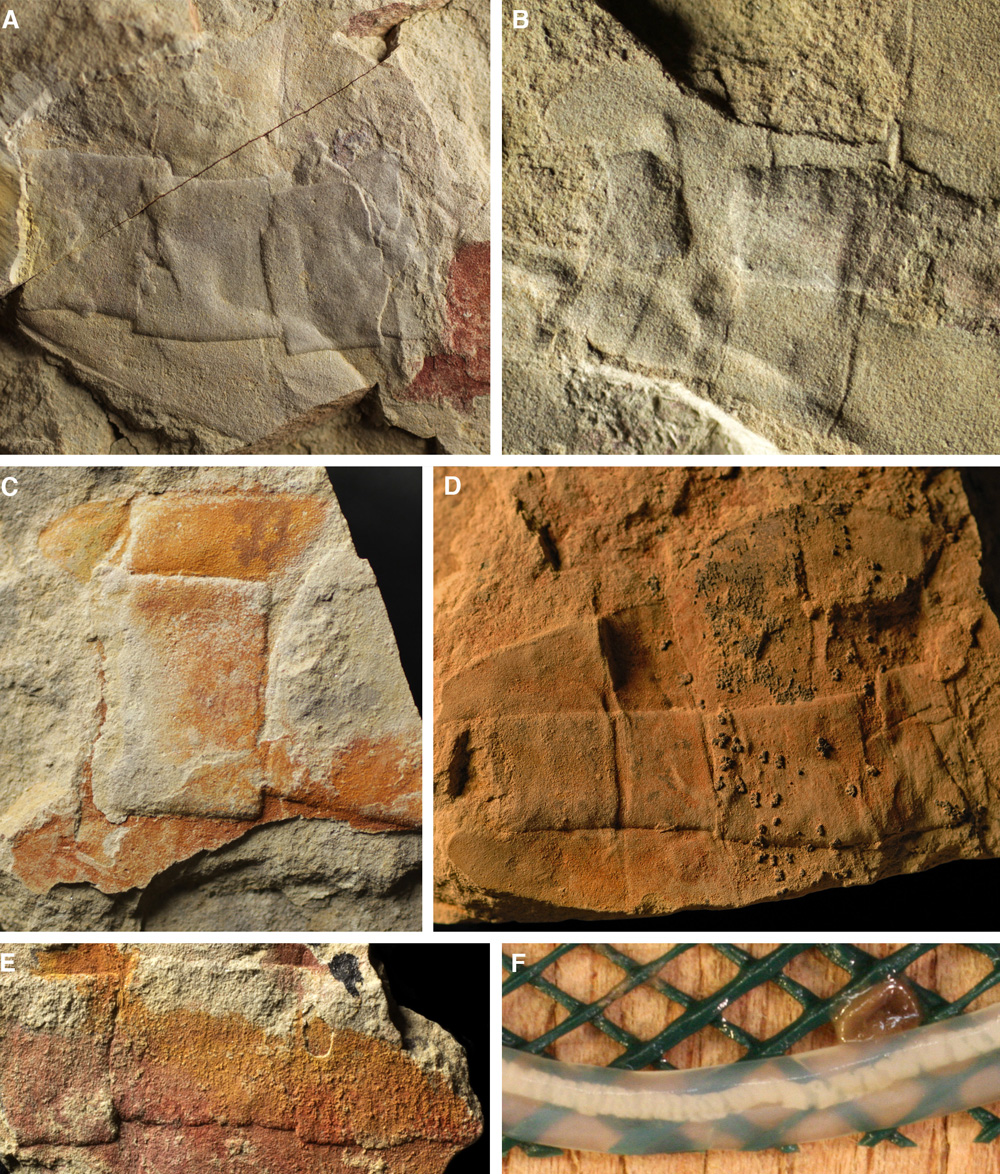

Emu Bay fossil site

The Emu Bay fossil site on Kangaroo Island, Australia, is home to a treasure trove of Cambrian fossils more than 500 million years old. Incredibly, many of these fossils are preserved with soft tissue, such as guts, skin and muscle. A new species of vetulicolian, Nesonektris aldridgei, was first found here in 2009, though it took researchers three years to discover the surprising notochord-like rod in the animal's tail. (Credit: Diego Garcia-Bellido)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

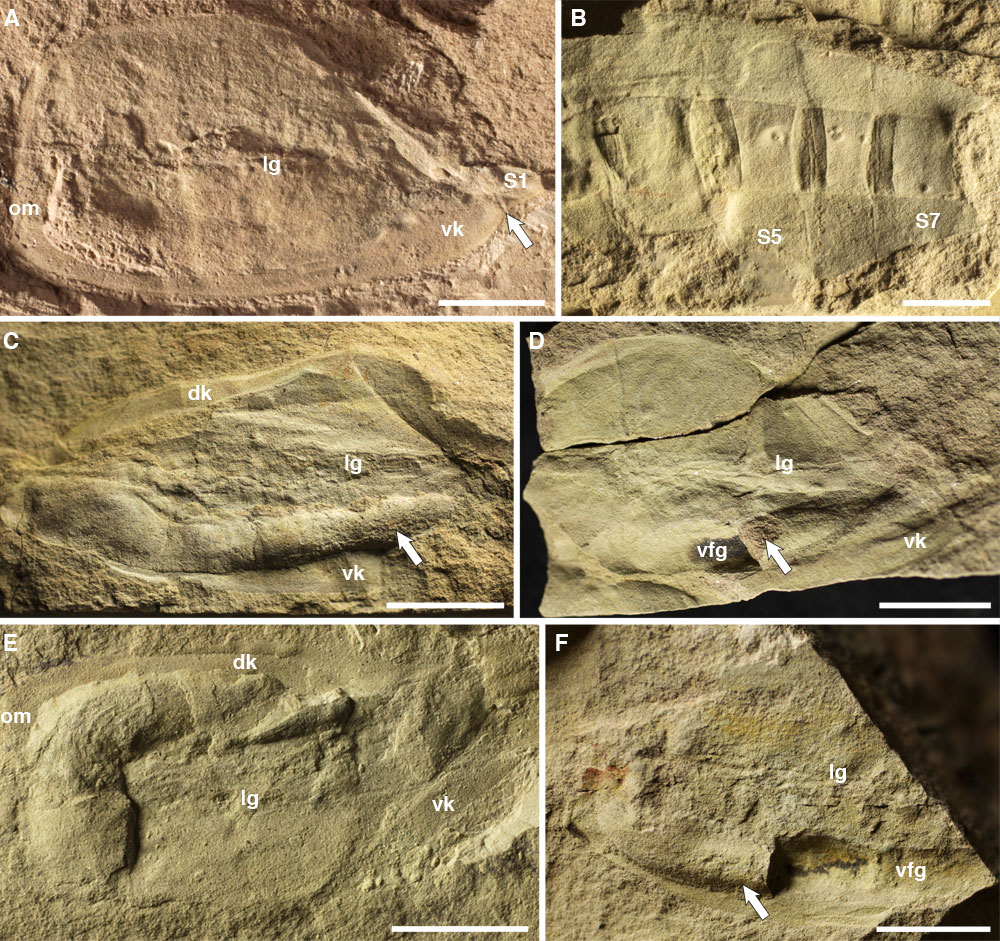

Something different

A detailed look at the rod-like structure discovered in 500-million-year-old vetulicolian fossils from the Cambrian. The blocky shape of the structure indicates that it is not a gut structure, according to a new study published in the journal BMC Evolutionary Biology. Instead, the structure looks more similar to modern nerve cords known as notochords. (Credit: Diego Garcia-Bellido)

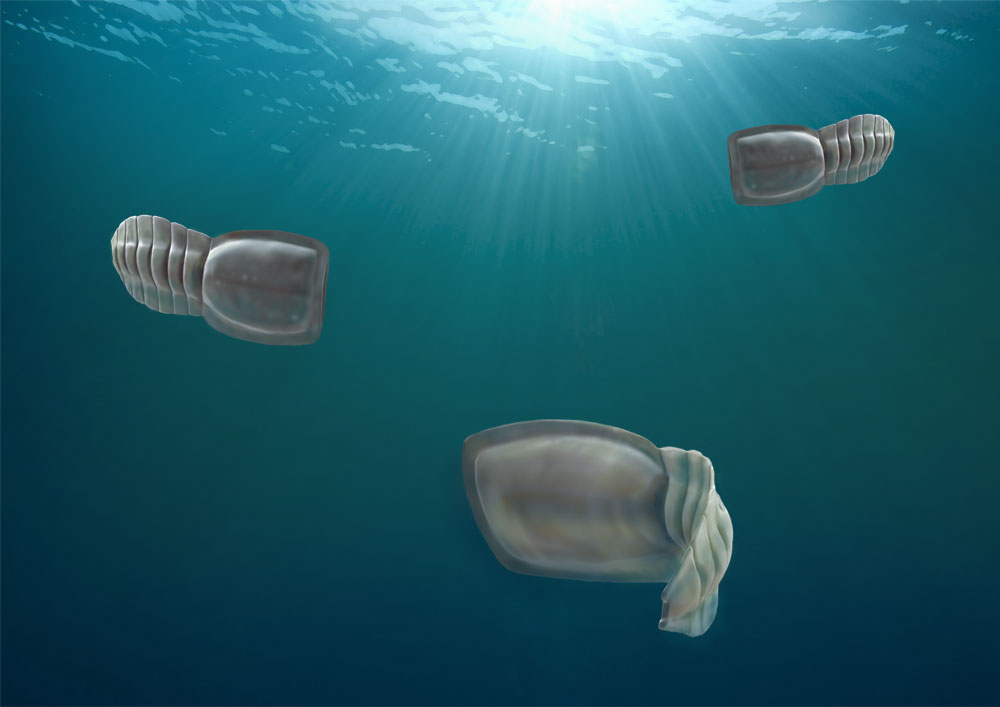

How the creature lived

Photographs of the Kangaroo Island vetulicolians show notochord structures (labeled "nc"). The labels S1, S4 and S7 indicate body segments on the creature's tail. On the other end, "om" labels the oral margin, or mouth of the creature. Vetulicolians likely swam through the water column, filter-feeding. (Credit: Diego Garcia-Bellido)

How the creature moved

An artist's impression of the Kangaroo Island vetulicolian swimming near the sea surface. There are 14 species of vetulicolian known from fossils around the world, including Southern China, Greenland and Canada. The new species found on Kangaroo Island, Australia, is dubbed Nesonektris aldridgei. "Nesonektris" is from the Greek for "island swimmer," and "aldridgei" is in memory of Dick Aldridge, a geologist and vetulicolian expert at the University of Leicester. (Credit: Copyright Katrina Kenny, 2014)

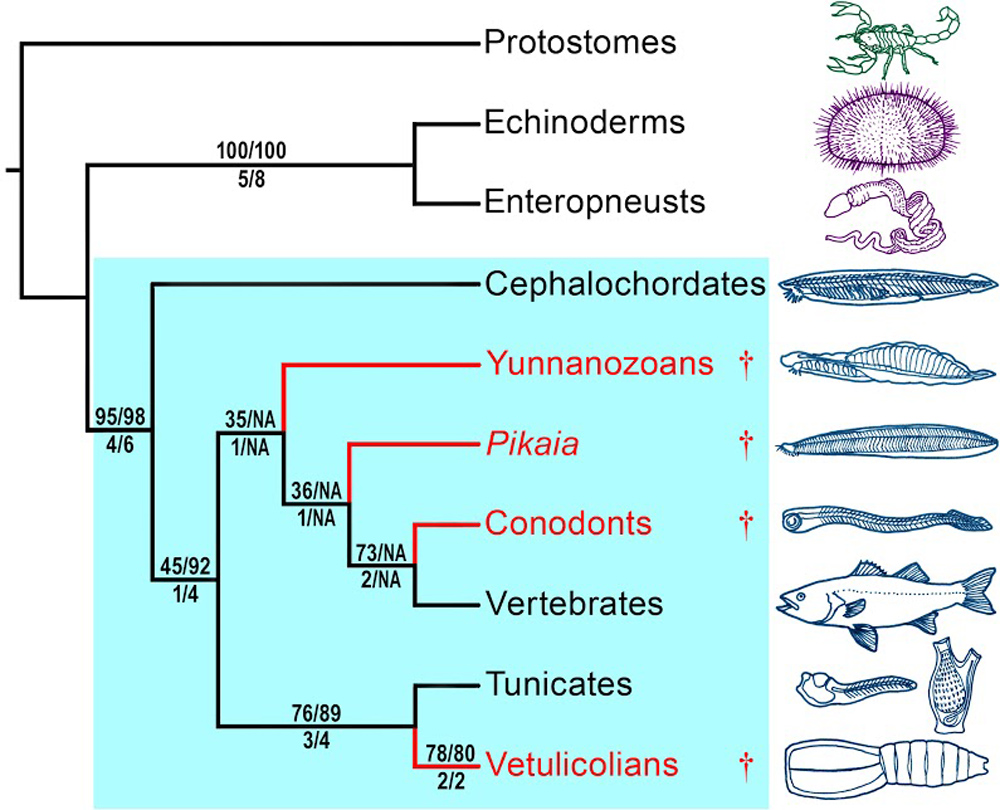

Family and relations

An evolutionary tree showing the position of vetulicolians compared with their closest relations. New research finding evidence of a primal spinal-cord-like structure in vetulicolian fossils suggests that the closest modern relative of these 500-million-year-old organisms are tunicates. Also known as sea squirts, tunicates are marine animals that anchor themselves to rocks and filter-feed off plankton. (Credit: Diego Garcia-Bellido)

The oldest animals

Vetulicolians date back to the Cambrian, making them some of the oldest animals on Earth. During this time, diversity of life expanded enormously in what is known as the "Cambrian Explosion." As a result, the fossil record is full of bizarre animals that sometimes bear little resemblance to life in the modern era. (Credit: Copyright Katrina Kenny, 2014)

Fossils to study

The anterior (head) fragments of vetulicolians from Kangaroo Island, Australia. The Emu Bay fossil site on this island preserves soft-bodied fossils, allowing researchers a good look at some of the oldest animals on the planet. In some fossils, gut contents are even preserved, revealing the animal's last meal. (Credit: Diego Garcia-Bellido)

Heads or tails

The tail segments of vetulicolians from Kangaroo Island, Australia. It was in these tail segments that researchers first noticed a long, rod-like structure that didn't match the description of the animal's gut. (Credit: Diego Garcia-Bellido)

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus