Solar Flares to Hit Earth in Rare One-Two Punch

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The sun launched back-to-back solar flares directly at Earth this week, but the resulting geomagnetic storms pose little danger, officials said today (Sept. 11).

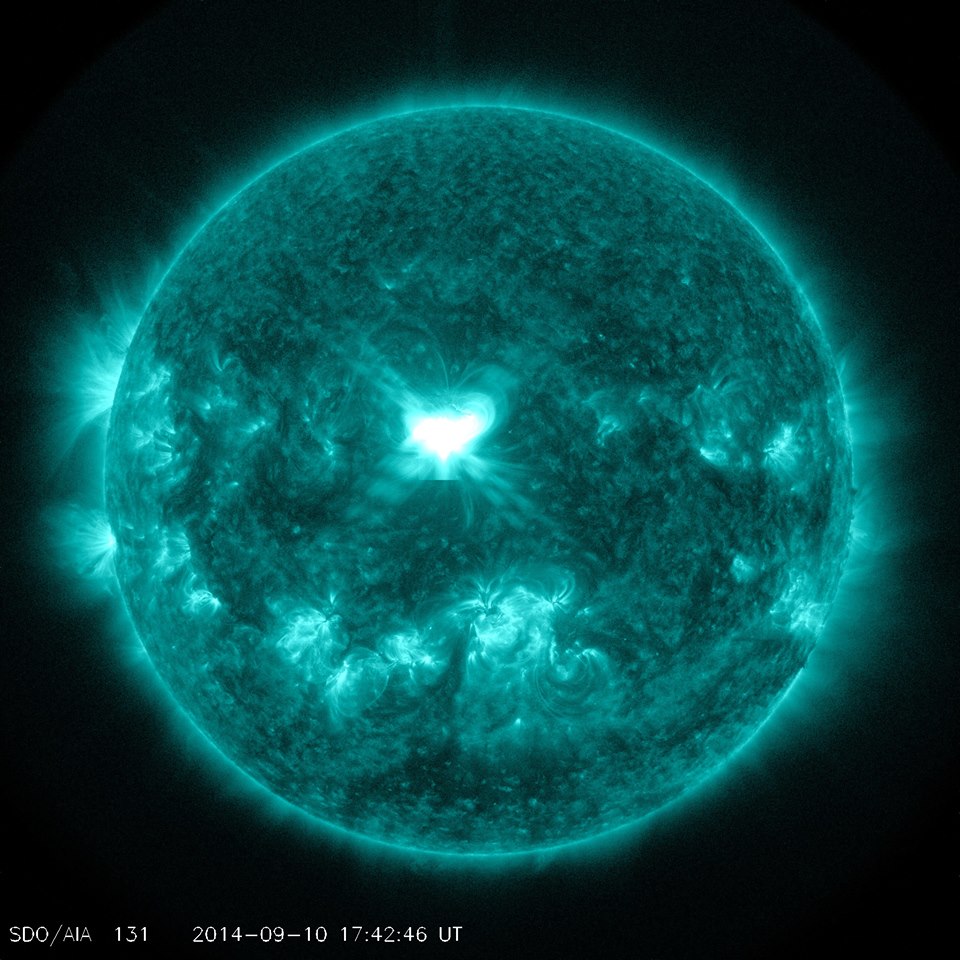

A strong X1.6-class solar flare erupted Wednesday at 1:46 p.m. ET from a sunspot more than 10 times the size of Earth, jetting out billions of tons of charged particles. The same sunspot also blasted out a minor solar flare on Monday.

Both eruptions of superheated solar plasma, called coronal mass ejections, came from sunspot AR2158. The sunspot, which is centered in the middle of the sun, aimed the CMEs directly toward Earth. Two solar flares in quick succession are relatively rare, said Tom Berger, director at the Space Weather Prediction Center, operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). [Sun Storm: See Images of the Amazing Solar Flares]

While the worst effects are predicted to miss Earth, scientists are worried about the combined potential of the two solar storms. Wednesday's powerful CME is speeding through space at 2.5 million mph (4 million km/h), catching up on the slower particle stream from Monday's smaller flare. The first solar storm will hit tonight, and the major solar storm will arrive late Friday morning, Berger said. There is a slight chance that interactions between the incoming particles and Earth's magnetic field could intensify the storm's power.

"The coupling is the holy grail," said Bill Murtagh, program coordinator at the Space Weather Prediction Center. "The sun just shot out a magnet, and that's going to interact with the Earth's magnetic field. How they couple determines how intense the geomagnetic storm is, and there's a lot of uncertainties until it hits."

Here is the most likely scenario: Earth will experience minor disruptions, such as fluctuations in power lines, radio signals and satellite transmissions, Berger said. Utilities and other operators have already been warned.

Near the poles, where the particles clash most strongly with Earth's magnetic fields, airlines may divert planes, because of interruptions in communications and an increased risk of radiation exposure.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

There is no radiation risk to people on the ground, Berger said. Nor does the geomagnetic storm pose a threat to electronics on the ground, such as computers and phones, he added. Astronauts aboard the International Space Station are also safe from the incoming CMEs.

More pleasantly, the solar storm will trigger spectacular auroral displays on Friday night, Murtagh said. In the United States, the northern lights could dance in the sky as far south as Oregon, South Dakota, the Great Lakes region and New England.

The unusual pair of solar flares comes as the sun is nearing the peak of its 11-year cycle, when sunspots and solar storms become more frequent. The powerful Sept. 10 eruption generated a shock wave that reached Earth Wednesday night, interrupting high-frequency radio transmissions and creating static on shortwave radios.

Sunspot AR2158 is a complex tangle of magnetic fields, fueling it with the energy to produce several solar flares. The sunspot was not particularly powerful for the year or the century, however. "By historical standards, this was not very large, but it packed a pretty good punch," Berger said. "This may be its swan song, however, because it's now in the process of breaking up."

Editor's Note: If you have an amazing aurora or general science photo you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Jeanna Bryner at LSphotos@livescience.com.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus