Two Venomous Jellies Discovered in Australia

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Two new species of jellyfish have been discovered off the coast of Western Australia. One is surprisingly large. The other is tiny. Both are extremely venomous.

These two newfound creatures are thought to pack painful stings that cause Irukandji syndrome, a constellation of symptoms that includes lower back pain, vomiting, difficulty breathing, cramps and spasms. Though Irukandji syndrome usually isn't life threatening, two people who were stung in the Great Barrier Reef in 2002 died from severe Irukandji-related hypertension.

Previously, only two jellyfish species from Western Australia were known to cause Irukandji syndrome. The discovery of the two new species brings the total number of Irukandji jellies worldwide to 16. [See Amazing Photos of Jellyfish Swarms]

Research scientist Lisa-ann Gershwin, who is director of the Australian Marine Stinger Advisory Services, described the new box jellyfish, or cubozoans, last month in the Records of the Western Australian Museum.

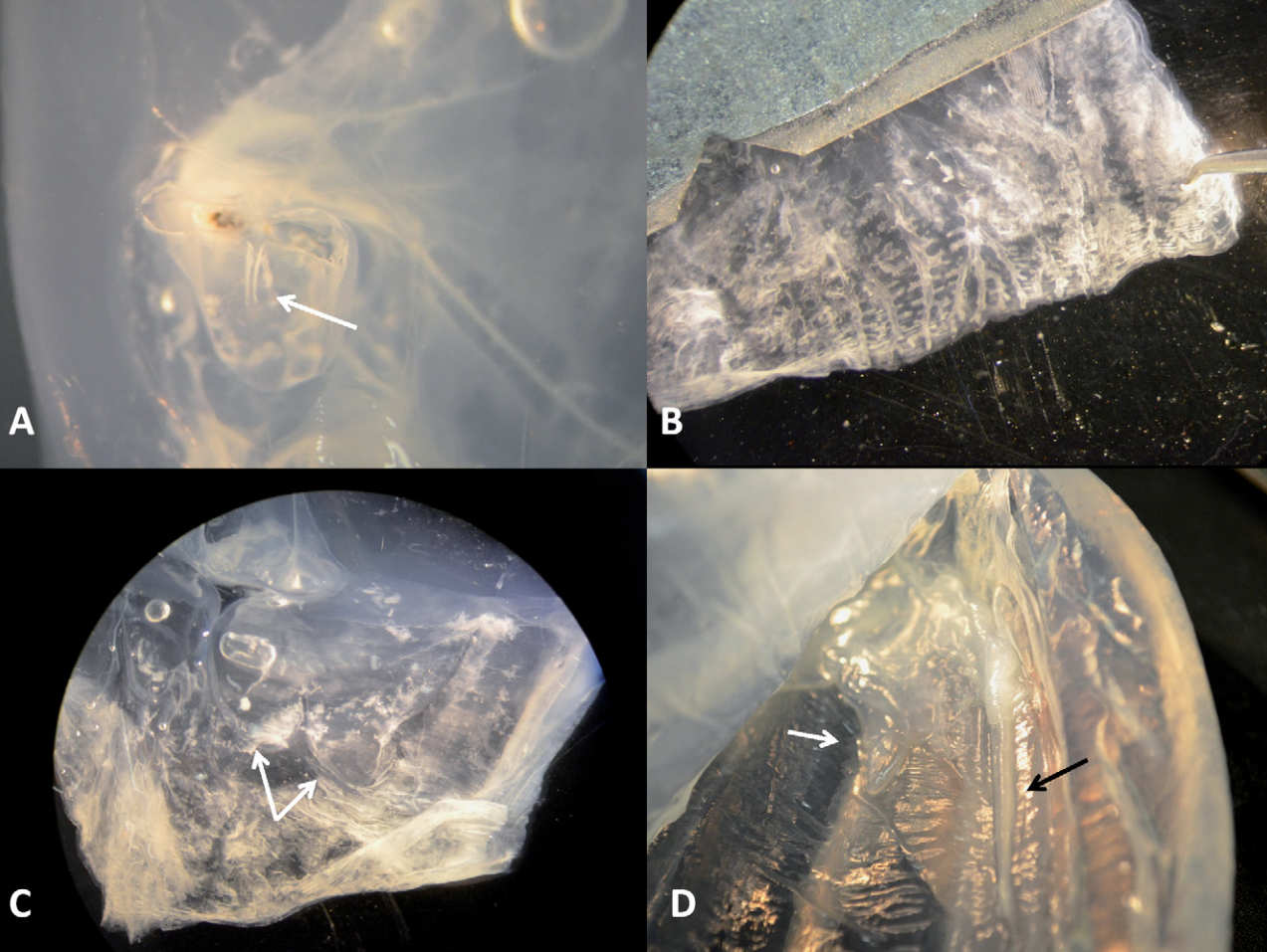

One of the newly identified creatures sports a clear, barrel-shaped body that is thick, warty and surprising large. Found in the Shark Bay and Ningaloo Reef regions, it's called Keesingia gigas. The name Keesingia for the new genus is a nod to the biologist John Keesing, who provided the first example of the creature, scooping up an immature specimen with a hand-held net in May 2012; gigas is Latin for "giant," referring to the animal's impressive size. While most Irukandji jellies are tiny and practically undetectable, adults of this species have a "bell" (the umbrella-shaped part of the body that doesn't include the tentacles) that measures 20 inches (50 centimeters) long.

There's one thing about this species that Gershwin said was "absolutely puzzling": So far, the jellyfish has only been photographed and collected without tentacles. Some jellyfish are tentacle-less and they've evolved other ways to catch food. But all known cubozoans have tentacles that they rely on to capture food, Gershwin said.

However strange it seems now, Gershwin thinks the answer to this riddle will probably turn out to be quite mundane.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We still have so few photos and specimens at this point that it is still within the range of 'just coincidence'" that delicate tentacles have been broken off in all cases, Gershwin told Live Science in an email. Or, perhaps, the tentacles are so fine as to have been easily overlooked.

Two reported of encounters with K. gigas resulted in symptoms consistent with Irukandji syndrome, Gershwin wrote. Though this jellyfish is painful to the touch for humans, other creatures seem to be able to get cozy with K. gigas without any problems. Three small leatherjacket fish were found living inside the holotype jellyfish's umbrella.

The other new species belongs to the already-known Malo genus. Its name, Malo bella, is a tribute to the creature's bell-like shape, its beauty and the Montebello Islands in Western Australia, where the species was first found, Gershwin wrote.

Compared with K. gigas, this critter looks a lot more like the tiny Irukandji jellies that scientists have already described. Its bell is less than an inch long (19 millimeters). And though it has not yet been associated with any particular stings, its close relationship to the venomous Malo kingi and Malo maximus suggests it is highly toxic to humans.

Little is known about the ecology of these two species. Learning more about the jellyfish's life history and how they behave could help scientists manage their potential impacts on public safety, Gershwin wrote. Each year, an estimated 50 to 100 people are hospitalized for Irukandji syndrome in Australia. Though only two deaths have been reported (the cases from 2002), researchers suspect drowning or heart attacks may have masked several other deaths related to Irukandji symptoms.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus