When Slime Ruled: Evolutionary Pause Tied to Earth's Stuck Plates

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

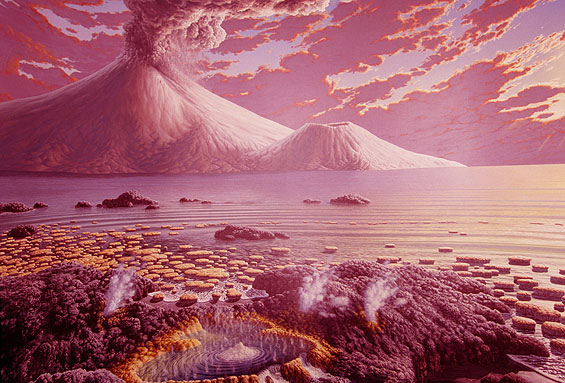

The "boring billion," the long evolutionary pause when slime ruled the Earth, might be due to a planetary cooling-off period that stalled plate tectonics, a new study suggests.

The so-called boring billion refers to the span from 1.7 billion years to 750 million years ago when algae and microbes had the run of Earth. Why boring? The long pause comes after these single-celled creatures mastered photosynthesis, meaning they could absorb energy from the sun instead of munching rocks and metal. After that extraordinary leap, there was little evolutionary advancement for another billion years, until the first complex life emerged.

Scientists have long sought an explanation for this big hold-up. Now, researchers think they've found a possible cause: the planet itself. It turns out plate tectonics also had a boring billion, according to research presented last week at the annual Goldschmidt geochemistry conference in Sacramento, California. The findings were also published in the June 2014 issue of the journal Geology.

Study authors Peter Cawood and Chris Hawkesworth of the University of St. Andrews in Scotland looked at how the continents behaved in the past by analyzing indicators of tectonic activity such as volcanic eruptions, global glaciations and giant gold and sulfur deposits. The continents weren't the same size through time, nor did they plow across the planet at the same speed. They found the continents grew quickly on the early Earth, had a stable middle age and are now entering a midlife crisis. [In Images: How North America Grew as a Continent]

"We are going from a time when you didn't destroy much crust to a time when you do," Hawkesworth said.

The transition from stability to destruction, which marks an uptick in tectonic motion, took place 750 million years ago, the same time as the emergence of complex life.

"This increase in activity could have kick-started a myriad of changes, including changes to levels of key elements in the atmosphere and seas, which in turn may have induced evolutionary changes in the life forms present," Cawood said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Blame Earth's temperature for the fits and starts in continental speed. According to the study, on the hot, young Earth, continents grew quickly, with about 70 percent of the "scum of the Earth" forming by 3 billion years ago, the researchers said. But the mantle, the hotter layer between the crust and the core, was still too warm for modern plate tectonics to rev up. Big fragments of continents couldn't slide into the mantle at collisions called subduction zones. So when the first supercontinent formed, the plates stuck together in a massive jam for a billion years while the mantle continued to cool off.

"This represents a unique period of environmental, evolutionary and lithospheric stability," Cawood said.

While algae and microbes were whiling away the boring billion, the continents were growing a gut, adding bulk to their bottom layer as the mantle and crust continued to gradually cool, the researchers think.

Finally, about 750 million years ago, the supercontinent started to break up when tectonics shifted into overdrive. The researchers think this time period is when the mantle was finally cold enough for Earth's crustal plates to be destroyed at subduction zones. The supercontinent started to tear apart, creating new ecosystems for life to occupy.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at Live Science's Our Amazing Planet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus