Greenland Summer Thaw: Will It Be a Big Melt?

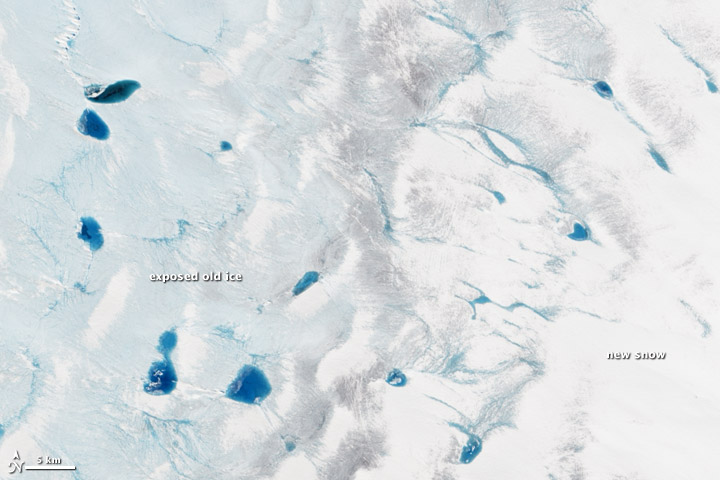

Late-spring warmth brings a stunning new color to the dazzling white palette that dominates Greenland in the wintertime. The warmth means Greenland's melt season has started, and sapphire-blue pools will soon dot the ice sheet as its upper layer of snow and ice transforms into water.

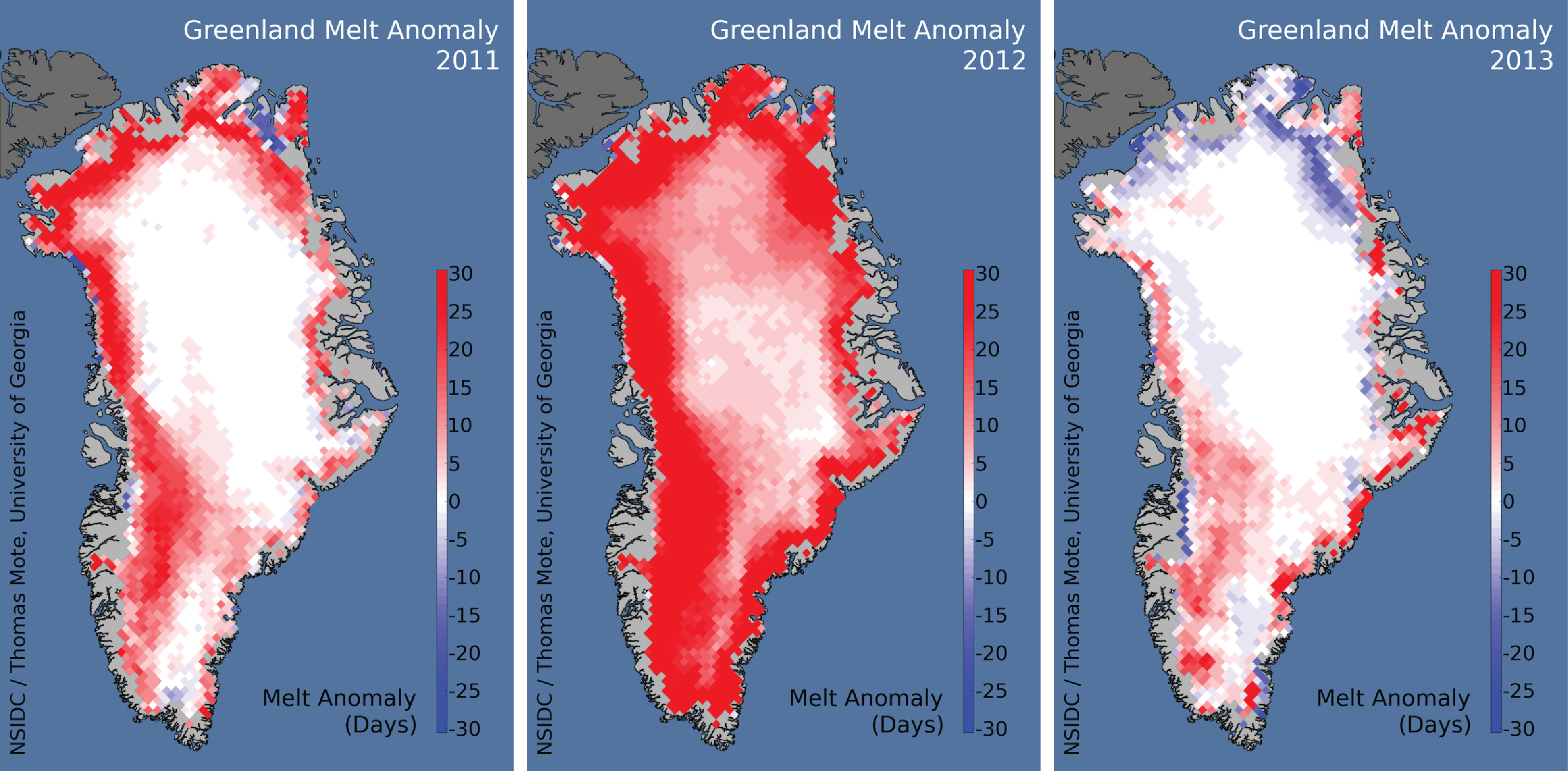

In 2012, a rare combination of weird weather, unusual warmth and forest-fire soot pushed the summer melt into overdrive, according to several recent studies. Nearly the entire surface of the Greenland Ice Sheet melted, even in the cold, dry regions where Greenland's elevation soars above 10,000 feet (3,048 meters). But in 2013, the summer melt returned to normal, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) in Boulder, Colorado. Almost half of the surface melted — ranking 14th in the 33 years since satellite tracking started in 1981.

Now, scientists are closely watching the 2014 summer thaw, to see if it will repeat 2012's impressive meltdown or return to the more mundane trend seen since 1981. So far, the signs point to an average year. [In Photos: Greenland's Melting Glaciers]

"We're not expecting anything exceptional for the next two weeks, but it's very difficult to look beyond that point," said Marco Tedesco, a Greenland melting expert at the City University of New York and a polar programs director for the National Science Foundation. "I think we will be able to make a good diagnosis by mid-July."

Some of the factors that led to a low surface melt in 2013 are still in play. The North Atlantic Oscillation, an atmospheric pressure pattern over the Atlantic Ocean, is still in a positive phase, as it was in 2013. The positive phase favors cooler conditions and summer snowfall across Greenland and warm, dry weather over Europe.

Also, meltwater has been slow to appear across the ice this year, Tedesco said.

"Besides a peak that happened in mid-May over the south part of Greenland, it doesn't look like there has been considerable melting so far," Tedesco told Live Science. "And, of course, there was a lot of melting in May in 2012 and only a little melting in 2013."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Widespread early melting can jump-start a big summer thaw, because melting kicks off an albedo feedback mechanism, Tedesco said. Albedo measures how much of the sun's energy is reflected. Fresh snow is more reflective than old ice and water. Melting sets up a feedback loop: When the young snow melts and exposes older ice, the darker ice absorbs more sunlight (has a lower albedo), which leads to more melting. (Melting in the snowpack also lowers its reflectivity.)

Other factors can also lower albedo, such as soot from pollution and forest fires. This effect could have contributed to the high-elevation melt in 2012, a recent study suggested. And forest fires are already raging in California, Alaska and Siberia, upwind of the powerful atmospheric jets that travel eastward to Greenland.

But summer snowfall can bury soot, muting its sunlight-absorbing power, Tedesco said.

"I would love a way to anticipate what's going to happen, but all of these factors have a really complicated effect," Tedesco said.

One new way to monitor the melt will be through the NSIDC, which is planning to build a daily Greenland melt tracking website, the agency said May 26.

The Danish Arctic research institutions are also providing daily updates on Greenland's surface melting.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.