Greenland's Never-Before-Seen Valleys Could Prolong Melting

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

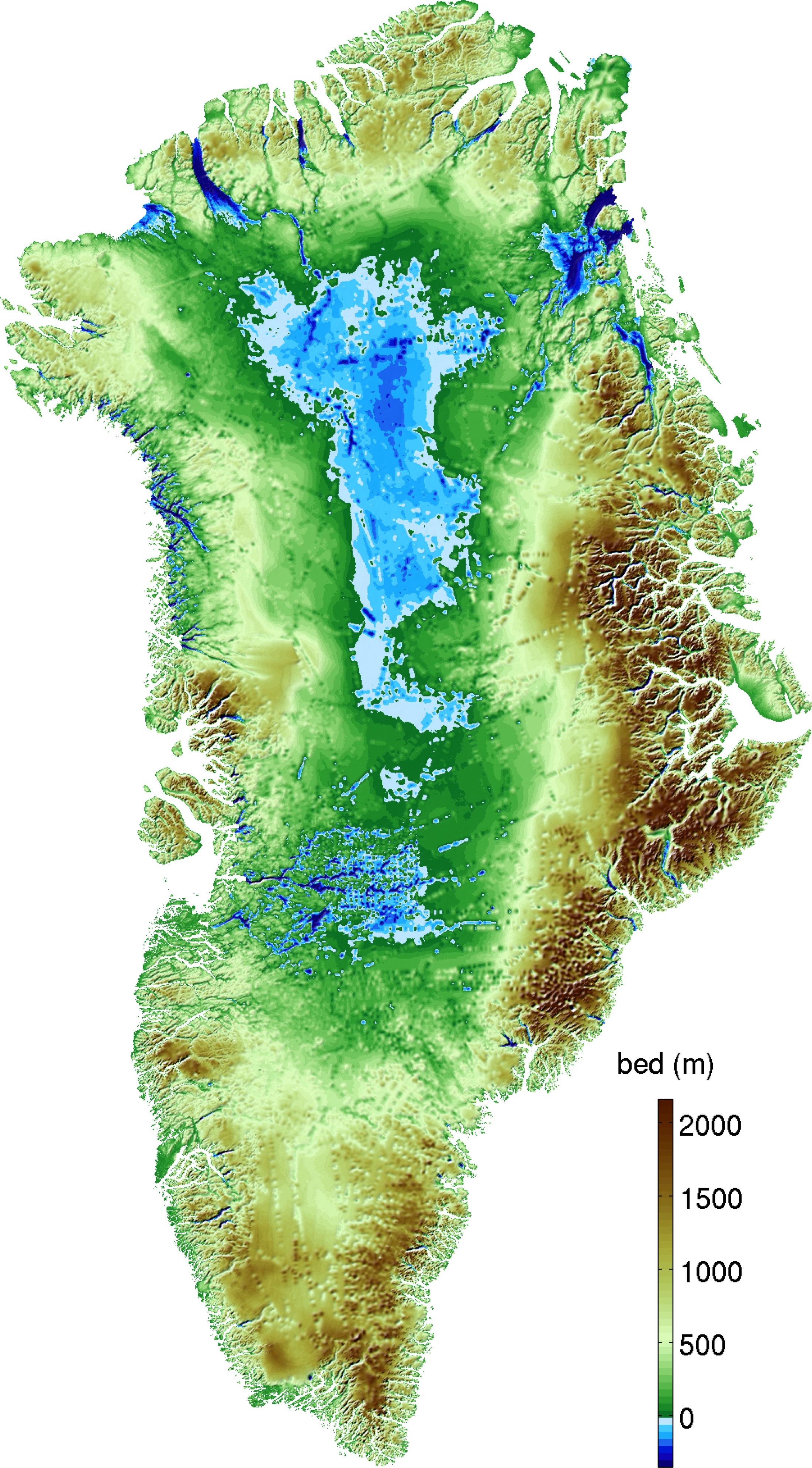

The decline of Greenland's glaciers could be more spectacular than predicted, because the island's valleys run longer and deeper than thought, a new study finds.

Researchers have created the most detailed map to date of Greenland's toothy rim — the canyons and mountains hiding beneath its thick ice. The survey revealed never-before-seen valleys that sink below sea level, which can make glaciers more vulnerable to melting, according to the study, published today (May 18) in the journal Nature Geoscience. Many glaciers thought to flow atop shallow beds are instead streaming atop the deep gorges, the researchers said. [Fly Over Greenland's Grand Canyon (Video)]

"Below each outlet glacier, there is a valley, which makes sense, but we didn't expect it," said lead study author Mathieu Morlighem, a glaciologist at the University of California, Irvine. "An outlet glacier doesn't have to have a valley, but we found that's the case for almost the entire periphery of Greenland."

Many glacial valleys identified in the new study are deeper and wider than those shown in earlier maps, and extend farther inland — an average of 41 miles (67 kilometers).

The findings mean some of Greenland's worst-case scenarios for melting ice need to be revised, the researchers said.

Melting from Greenland accounts for about 10 percent of sea-level rise, but in recent years, a handful of reassuring studies predicted that the pace would slow in coming decades. One reason proposed for the slowdown is that glaciers are shrinking back into high fjords (the name for long, narrow canyons with steep sides). The fjords would squeeze the glaciers in place, halting their retreat, and the high elevation would raise the ice out of reach of warm ocean water.

Finding submarine valleys in Greenland heightens the risk of widespread melting, Morlighem said. Because the canyon bottoms sit below sea level, if glaciers retreat into their depths, the ocean will follow. There's no escape from the heat.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The ice will stay in contact with the ocean for longer than we thought," Morlighem told Live Science. "Greenland is more vulnerable than we thought, but we can't say by how much."

The researchers estimate half of Greenland's outlet glaciers could undergo massive melting. (That's 60 of 123 glaciers, draining 88 percent of the ice sheet.)

In a nutshell, Morlighem and his colleagues built the map by taking the surface elevation of the ice and calculating the ice thickness, then subtracting one from the other.

However, the new map won't be the final word on Greenland's future melt. Mapping the topography there means charting one of the world's last great regions of terra incognita. The thick ice, remote location and harsh climate make surveys difficult, and there is still much detail to uncover.

But Morlighem said the specifics of future Greenland maps are unlikely to change significantly.

"The maps will be more and more accurate, but they won't be night and day like it is today," he said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus