Hot, Hot, Hot: National Park Seen from Orbit

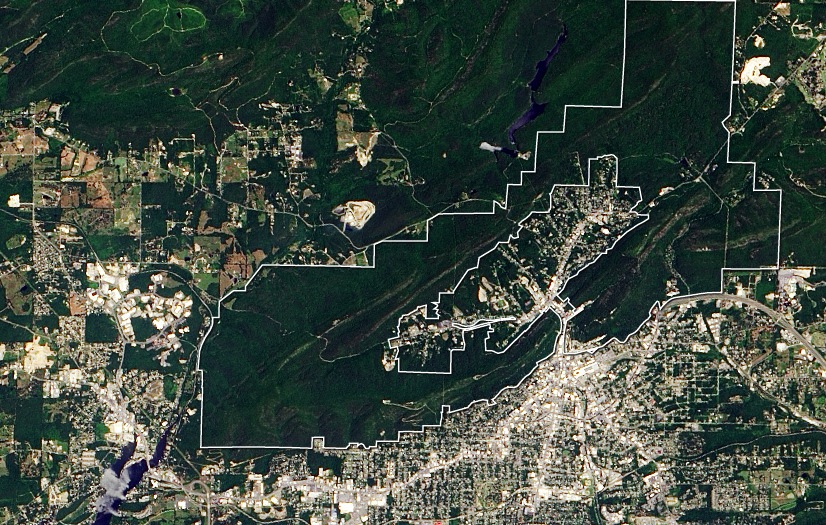

The smallest, most urban national park in America appears in a new satellite image snapped by Landsat 8's Operational Land Imager.

The satellite snapped this photo on June 14, 2013, according to NASA's Earth Observatory. Landsat 8 launched in May of that year and images the planet's surface in spectrums ranging from visible to thermal-infrared light, according to NASA.

Hot Springs National Park in Arkansas sits next to and partially overlaps the city of Hot Springs, home to 35,000 residents. In the new image, the city is visible on the lower right-hand side of the photo. The park encompasses 5,550 acres (2,250 hectares), including the island of buildings in the green Ouachita Mountains.

The United States acquired what is now Arkansas in the 1803 Louisiana purchase. The hot springs were a rudimentary tourist attraction by the 1830s, according to the National Park Service. In 1832, Congress and President Andrew Jackson set aside the springs as a preserve, though private building continued.

Today's Hot Springs National Park is a remnant of construction completed mostly between 1912 and 1923, according to the NPS. The picturesque Bathhouse Row features luxurious spas with stained glass and marble walls. In 1921, the hot springs were designated as a national park.

The government even operated a free bathhouse in the park. Between 1922 and 1948, the public bathhouse was home to a clinic for sexually transmitted infections, and was one of the first clinics in the country to use penicillin, according to the NPS.

Unlike the hot springs at Yellowstone National Park, which are preserved in their natural state, Hot Springs' water has long been engineered and managed. Also unlike Yellowstone, the "hot" in these springs comes not from volcanic activity, but from depth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Water from rain seeps down deep into the Earth, where pressure heats everything up, according to the NPS. After a few thousand years underground, this heated water makes its way quickly to the surface through fractures, discharging at springs before it has a chance to cool.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus