Scientists Can Know Your Intentions

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

New experiments show it is possible for computers to detect, at a higher level of sophistication than ever before, people's intentions for the future, neuroscientists reported yesterday.

The findings could yield a big improvement in brain-computer interfaces, could help the disabled control robotics with their minds and could make it so a computer could read our minds far better than is currently possible.

For decades, scientists have investigated ways that people might control machines just by thinking. Neuroscientists have known that brain-computer interfaces can read out motor functions, such as thinking about moving something from left to right, explained researcher John-Dylan Haynes, a neuroscientist at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany. These studies have, for instance, led to more advanced prosthetic limbs.

While such findings can help control simple brain-computer interfaces, "if you're hunting for a letter on a keyboard, it can take quite a while to spell out a whole word just by thinking a cursor up and down," Haynes said.

To build a more complex brain-computer interface, scientists would like "to tap into higher-level information. This means more abstract desires, such as 'reply to my email,'" he explained. "Reading such intentions in the brain was not previously thought possible."

Now Haynes and his colleagues have for the first time revealed that such wishes in the brain can get read, using a new combination of advanced brain scanners and sophisticated computer algorithms.

The scientists let volunteers freely and secretly choose between two possible tasks, either adding or subtracting two numbers. They were then asked to hold in mind their intention for roughly three to 11 seconds until the relevant numbers appeared on a screen. The subjects did not know which numbers would appear. After the paired numbers were shown, volunteers were then shown four numbers, one being the correct answer for addition, one being the correct answer for subtraction, and two being wrong answers.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

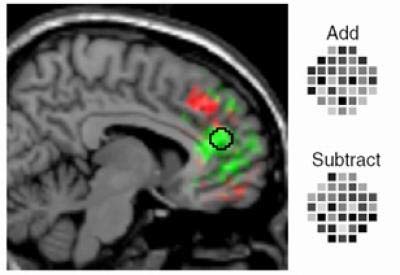

The researchers observed brain activity [image] during these experiments using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). They proved able to recognize a person's intentions with 70 percent accuracy based solely on their brain activity, even before the volunteers had seen the numbers and started to perform the calculation.

"You could imagine a sophisticated controller for a PlayStation that would allow you to think 'do a flip on a snowboard' instead of just left, right, up, down," Haynes told LiveScience. "Of course, an MRI scanner costs $2 million, so don't expect this to get shipped with the latest Xbox."

Future investigations could implant electrodes in the brains of paralyzed patients to help them better control devices. "However, there are medical limitations there. These are regions in the middle of the brain that are not that easy to get to without damaging tissue," Haynes said.

The researchers specifically found that a region of the brain near the front of the head, called the anterior medial prefrontal cortex, "was where you put intentions or plans for later usage," Haynes said.

A region slightly further back in the brain, known as the superior medial prefrontal cortex, "is where you store the plan you are actually executing right at the moment," he added. "Intentions for future actions that are encoded in one part of the brain need to be copied to a different region to be executed."

"A year and a half ago, people said it was insane to do this—to read something as subtle as a mathematic operation," Haynes said. "It turned out there was considerable information in the brain to work with."

Haynes cautioned this research, detailed in the Feb. 8 online issue of the journal Current Biology, could not lead to a general mind-reading device. "You need to observe people thinking a certain number of different kinds of thoughts before you can determine what patterns of brain activity are linked with different thoughts," he said.

This research could make it possible to read intentions in people who are holding back information, potentially useful for terrorist screening, Haynes said.

"This certainly raises the ethical questions of whether or not one should be allowed to read concealed thoughts in other people's brain activity, or whether or not that would violate mental privacy," he added. "It's not necessarily something you'd want at, say, a job screening."

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus