Peer Inside an Asteroid: Peanut-Shaped Space Rock's Insides Revealed (Photos)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The innards of an asteroid have been measured for the first time.

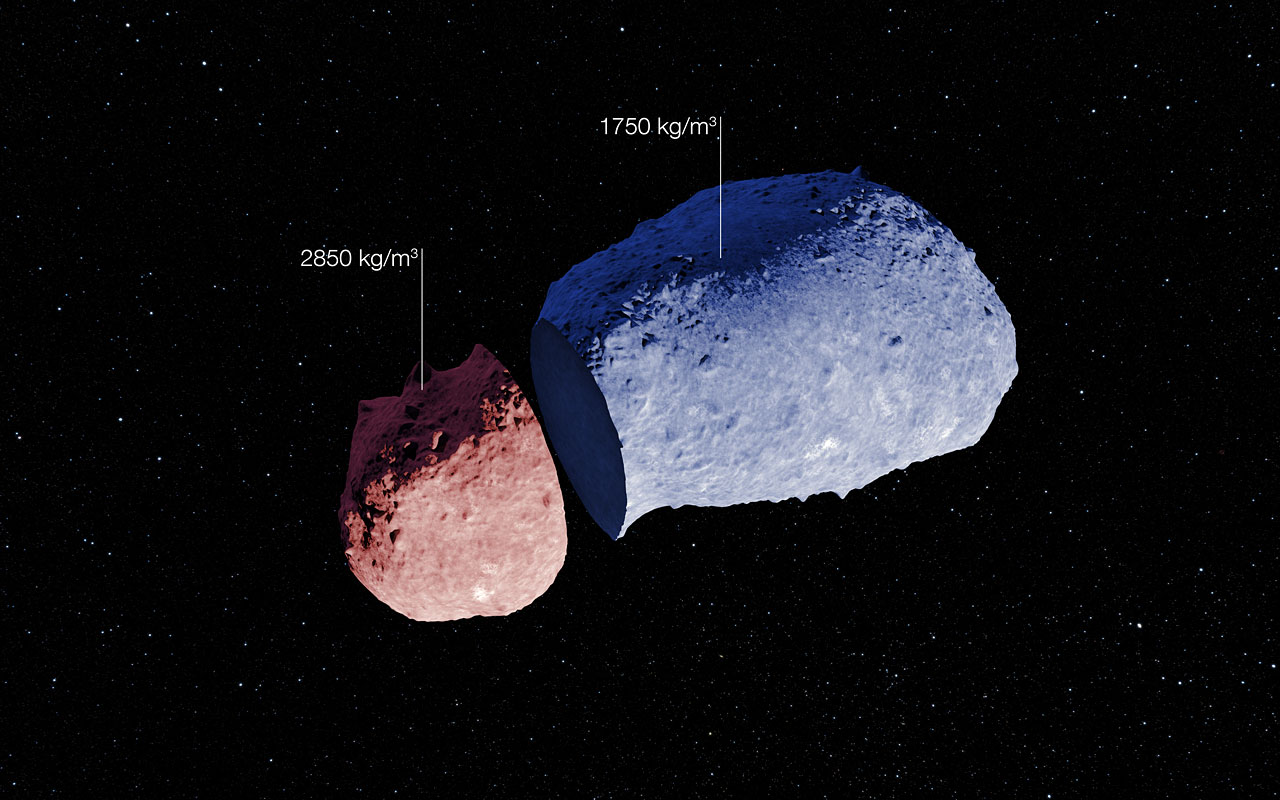

Scientists using a European Southern Observatory telescope have made precise measurements of Asteroid Itokawa's density. They discovered that different parts of the asteroid have different densities, giving the scientists clues about the asteroid's formation in the solar system. The researchers explain the strangely shaped asteroid Itokawa in a new video.

Itokawa is a stony composite asteroid. The peanut-shaped space rock is about 1,755 feet (535 meters) long on its longest side and takes about 556 days to orbit the sun. Scientists measured the density by studying images of Itokawa taken by the New Technology Telescope at the La Silla Observatory in Chile, as well as by other telescopes, from 2001 to 2013. Stephen Lowry, a researcher at the University of Kent, and his team measured how the brightness of the space rock varies during its rotation, ESO officials said. [See more photos of asteroid Itokawa]

"This is the first time we have ever been able to determine what it is like inside an asteroid," Lowry said in a statement. "We can see that Itokawa has a highly varied structure — this finding is a significant step forward in our understanding of rocky bodies in the solar system."

By looking at the change in Itokawa's brightness over time, the researchers tracked how the asteroid's spin period changed over time. By understanding that information plus its shape, the astronomers could also map the asteroid's interior density, ESO officials said.

Lowry and his colleagues found that sunlight was actually affecting the way the asteroid spins. Thanks to some very precise measurements, the team found that Itokawa's rotation period changes by 0.045 seconds per year, ESO officials said. While this may seem like a miniscule amount, it's something that can only happen if the two halves of the peanut-shaped space rock have different densities.

Until now, scientists had estimated asteroid interior properties through overall density measurements, ESO officials said. Now that they know the internal structure of an asteroid can vary, scientists can try to work backward to see how the space rock formed. Scientists now think it's possible that two parts of a double asteroid crashed together and merged to create Itokawa, ESO officials said, although no one is sure exactly how it formed.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Finding that asteroids don't have homogeneous interiors has far-reaching implications, particularly for models of binary asteroid formation," Lowry said in a statement. "It could also help with work on reducing the danger of asteroid collisions with Earth, or with plans for future trips to these rocky bodies.”

Japan's Hayabusa spacecraft collected tiny dust grains from Itokawa in 2005 during a 1.25 billion-mile (2 billion kilometers) mission that took seven years to complete. The probe returned to Earth with the space rock samples in 2010. The unmanned Hayabusa arrived at Itokawa when the asteroid was about 180 million miles (290 million km) from Earth.

Scientists in Japan are also considering a follow-up to the Hayabusa mission called Hayabusa 2. The new probe would launch to and sample 1999 JU3, a carbonaceous asteroid.

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus