Photos: Snow Leopard Captured and Collared in Nepal

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Snow Leopard Angry!

In a first for Nepal, scientists captured and collared an elusive snow leopard to track the movements of the endangered cat. This male snow leopard was captured using a foothold snare. Conservationists say it was not harmed during the capture on Nov. 25, 2013.

Drug Dart

The snow leopard was immobilized with a drug combination of Telazol and Medetomidine so that conservationists could safely put the tracking collar around its neck.

Sleepy Leopard

Dr. Rinjan Shrestha, a conservation scientist for the Eastern Himalayas Program, WWF US, assesses the depth of the anesthesia by gently tapping the snow leopard. The sedative took about 10 minutes to take effect.

Collar Time

The snow leopard was collared with a GPS Plus Globalstar collar (Vectronics Aerospace Inc., Germany). The collar is programmed to take GPS locations or 'fixes' at four-hour intervals. It is also fitted with mortality, temperature and activity sensors.

Ghanjenzunga

The collared snow leopard was a 5-year-old adult male named Ghanjenzunga, after a local deity. It weighed 88 lbs. (40 kg) and measured 6.3 feet (193 cm) from the base of its head to the base of its tail.

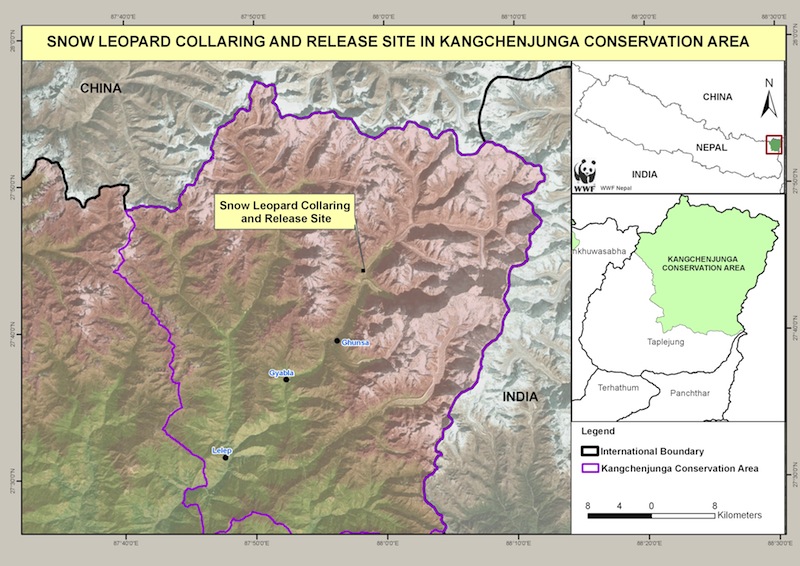

Kangchenjunga

The leopard was collared in eastern Nepal's Kangchenjunga Conservation Area.

Historic Collar

The collared snow leopard was released into the wild at approximately 10:45am on Nov. 25, 2013. This is the first time that satellite technology is being used to track the cats in Nepal.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Two Year Tracking

Conservationists say Ghanjenzunga will be intensively monitored through 2015. They hope data from the collar will reveal key information on the snow leopard ecology and behaviour crucial to framing conservation strategies in the future.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus