Why Monkeys and Apes Have Colorful Faces

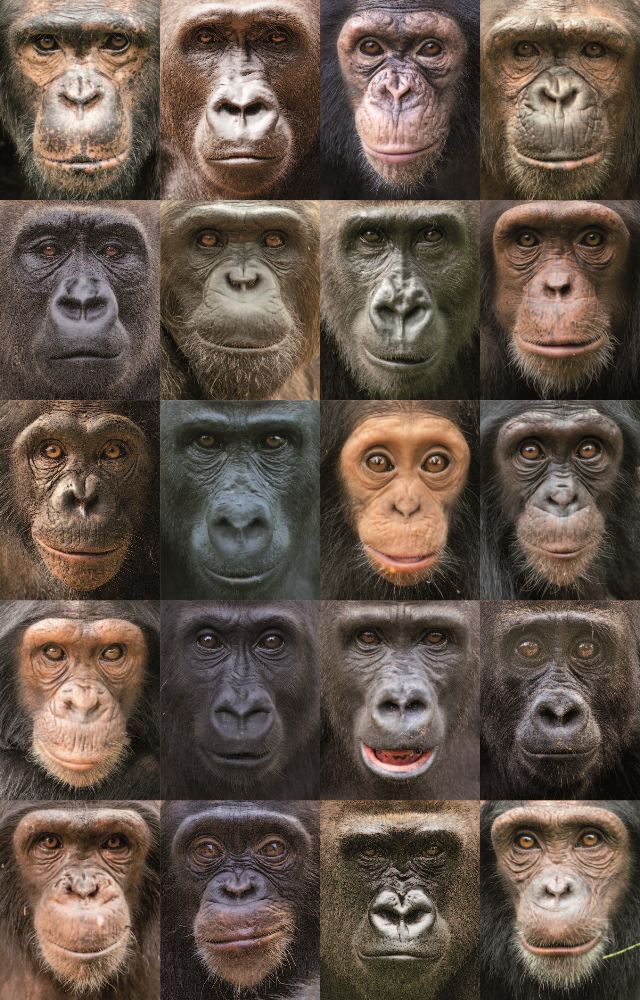

One face, two face, red face, blue face — the palette of primate faces is rich and varied, and a new study explains why.

For Old World monkeys and apes, species that live in larger social groups have complex, colorful facial patterns, whereas those that live in smaller groups have simpler, plainer faces, the study researchers found. Facial diversity might make it easier to identify individuals in bigger groups, scientists say.

"Faces are really important to how monkeys and apes can tell one another apart," study researcher Michael Alfaro, an evolutionary biologist at UCLA, said in a statement, adding, "We think the color patterns have to do both with the importance of telling individuals of your own species apart from closely related species and for social communication among members of the same species."

Old World monkeys and apes, which are native to Africa and Asia today, have diverse social structures. Mandrills, for example, live in groups of up to 800 individuals. Other species are much more solitary — orangutan males travel and sleep alone, and females live only with their young. Still others, such as chimpanzees, have "fission-fusion" societies, living in small groups and occasionally convening in very large groups. And hamadryas baboons have complex hierarchies involving harems, clans, bands and troops. [Image Gallery: Snapshots of Unique Ape Faces]

In the study, evolutionary biologist Sharlene Santana, now at the University of Washington, developed a way to quantify the complexity of primate faces in photographs. Santana divided the face into different parts, classified the color of each part (including the hair and skin), and scored the face based on the total number of different colors.

To see whether the animals' habitat influenced facial complexity, the researchers considered geographic location, tree canopy thickness, rainfall and temperature. The team also took into account evolutionary relationships among the primate species.

Facial complexity corresponded to the group size and number of closely related species in the same habitat, whereas facial pigmentation — how light or dark the face is — was better explained by geographic factors, the results showed. The findings were detailed online Nov. 11 in the journal Nature Communications.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In human society, Facebook provides a way of keeping track of one's friends. "Humans are crazy for Facebook, but our research suggests that primates have been relying on the face to tell friends from competitors for the last 50 million years and that social pressures have guided the evolution of the enormous diversity of faces we see across the group today," Alfaro said.

The team also found that in Africa, Old World monkeys and apes with darker faces lived nearest to the equator and those with lighter faces lived farther away. Primate species living in more tropical, forested areas also had darker faces, they said.

But facial complexity was not related to geographic location or habitat. Instead, complexity appeared to depend on the size of the social group: Species that formed larger groups had more diverse faces.

In a previous study, the researchers found the opposite pattern among primates from Central and South America: New World monkeys that lived in larger groups had simpler facial patterns.

"Our research suggests that faces have evolved along with the diversity of social behaviors in primates, and that is the big cause of facial diversity," Alfaro said.

Editor's Note: This article was updated at 9:00 am ET Nov. 22, to correct Dr. Santana's title and affiliation. She is no longer a postdoctoral fellow in the Alfaro lab.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.