Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Zak Smith is an attorney for the Marine Mammal Protection Project at NRDC. This Op-Ed is adapted from one that first appeared on the NRDC blog Switchboard. Smith contributed this article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Something bad is happening in the ocean. No one's certain what's causing it, but in the past three months more than 550 bottlenose dolphins have stranded along the Atlantic Coast and there's no indication that the strandings are letting up. While researches rush to catalog data on the dolphins' deaths, larger questions loom — is the Atlantic coastal ecosystem broken, and are humans the cause?

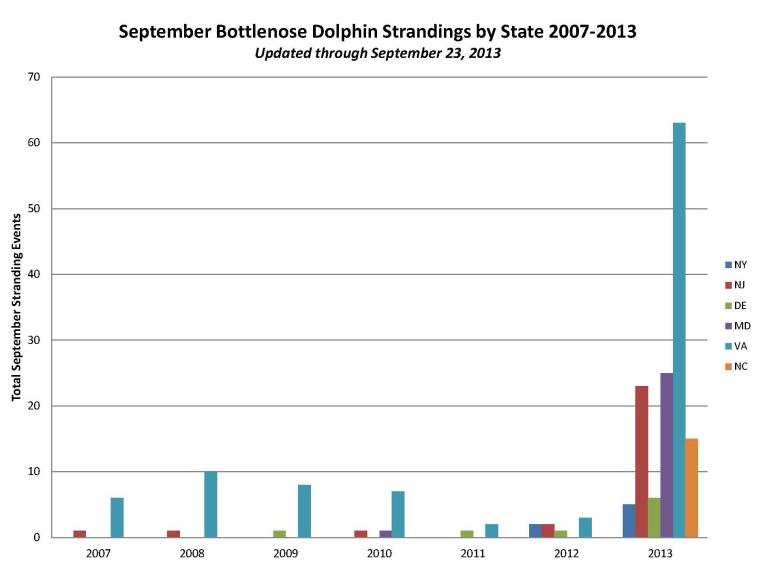

Yes, dolphins strand all the time, but not like this. As shown below in the figure from the National Marine Fisheries Service, strandings have skyrocketed this year, especially in Virginia and fanning out north and south, with large numbers in Maryland, New Jersey and North Carolina.

It would be easy to finger the morbillivirus, which has ravaged bottlenose dolphin populations in the past and is showing up in the necropsies conducted on these dolphins. But, the high death count and secondary infections by fungi, bacteria and parasites have some scientists questioning whether the deaths of these dolphins — "sentinels of ocean health" — are a sign of a coastal ecosystem sickened by human activities. Humans have been degrading the coastal environment for decades, with agricultural runoff, oil spills, noise pollution, biotoxin accumulation, etc. Even if the morbillivirus is the chief culprit, are these dolphins succumbing to the virus now because their immune systems have been degraded by an environmental onslaught?

For example, as Dina Fine Maron explains in a Scientific American article earlier this month, dolphins sickened by the virus may have skipped a few meals if they didn't feel up to foraging, relying on their fat stores. Bad idea: biotoxins accumulated in fat would have then released, subjecting the dolphins' immune systems to toxins that could have hampered their immune responses.

Unfortunately, scientists collect little to no data on dolphin biotoxin accumulation, infection rates, or other indicators of a sickened ecosystem. And, as Maron notes, "that's a problem because more could be happening than we know with potential lasting consequences for oceans."

My colleague, Michael Jasny, has written about the 2010 to 2013 Gulf of Mexico bottlenose dolphin die-off that is still ongoing and roughly coincides with the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster. As the National Marine Fisheries Service notes, the majority of recent unusual mortality events have been caused by biotoxin accumulation from harmful algal blooms. Here, the toxins are produced by living organisms (algal blooms), not sourced from human pollution, but it's a distinction without much meaning as the number and intensity of algal blooms will likely rise as a result of climate change, which is caused by human pollution.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

So, what are the "sentinels of ocean health" telling people? Seems to me that the writing on the wall keeps getting larger and bolder — society can't continue to degrade coastal environments and pour climate-change-producing pollution into the air and not expect our oceans and dolphins to give out.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus