Is Fertility an Option for Women with BRCA Cancer Gene? (Op-Ed)

Dr. Avner Hershlag is chief for the Center for Human Reproduction at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, N.Y. He contributed this article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Thank you, Angelina Jolie, for making your private dealing with the BRCA gene public.

Many patients are grappling with the new reality presented to them when they are diagnosed with having the BRCA gene mutation that can lead to breast cancer. Everyone has a BRCA gene. But a very small change in the gene — a mutation, designated BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 — may change the course of your life. With those mutations, an individual's lifetime chance of developing breast cancer is greater than 80 percent and the chance of developing ovarian cancer is greater than 30 percent. And, there are other cancers that may develop at a higher frequency, such as prostate cancer, in BRCA-2 patients.

There's a lot of talk today in the media about what can be done to prevent breast and ovarian cancer from developing in BRCA-positive patients. Many women choose, like Jolie, to have a double mastectomy with immediate reconstructive surgery of the breasts. Many plastic surgeons have developed expertise in reconstructing breasts after mastectomy and the aesthetic results are excellent in most cases. In addition, women ages 35 to 40 may choose to remove their ovaries, hopefully after completing their family.

Completing their family! Can that be safely done? What if you're a young woman diagnosed with breast cancer, and you haven't started your reproductive life yet? What if you don't have cancer, but because of your family history you have been tested, and found positive, for the BRCA gene mutation?

Specialists in reproductive medicine are able to help women with the BRCA gene take control over their reproductive life — securing fertility is now possible, whether or not cancer has emerged. If you have been diagnosed with a BRCA gene mutation but don't yet have a partner with whom you would like to have children, or if you are in the midst of pursuing a career and want to defer having children, new medical techniques can help you achieve these goals.

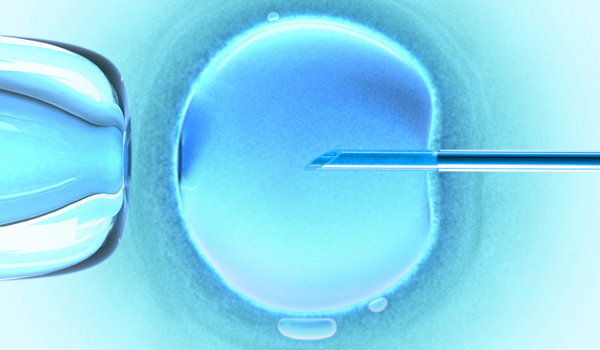

For women without a partner, physicians offer egg freezing. This requires a short course of treatment with fertility drugs, and eggs are retrieved from the ovaries while the patient is under anesthesia. The procedure lasts no more than 20 minutes, on average. Eggs can be frozen for years, and thawed out when the patient is ready to have a child, fertilized with her partner's sperm. New technologies have allowed for excellent survival of eggs coming out of the "deep freeze," with good fertilization and pregnancy rates.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For those individuals with a BRCA gene mutation who have a partner, they can undergo a similar procedure, but their eggs can be fertilized immediately and frozen as embryos. Women can therefore secure their fertility before they choose to have their ovaries removed: Pregnancy can be achieved with frozen eggs or embryos after the ovaries are removed.

But what about passing along the BRCA gene mutation to children? If a parent has the BRCA mutation, children — whether boys or girls — have a 50 percent chance of carrying the gene.

Through genetic diagnosis of the embryos — Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis, or PGD — doctors are now able to determine which embryos carry the abnormal BRCA gene. Doctors only transfer BRCA-free embryos to a mother's womb, practically ensuring that a parent will not transmit this treacherous gene to her children.

Ultimately, as more patients with the BRCA gene mutation choose PGD before the implantation stage of in vitro fertilization, fewer women and men will have that gene in generations to come.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus