Ancient Insects Get Intricate Portraits

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Abby Telfer is FossiLab Managerat the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (NMNH). This article was adapted from her poston the blog Digging the Fossil Record: Paleobiology at the Smithsonian, where this article first ran before appearing in LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Plants and insects form two of the most diverse groups of organisms on the planet, and their interactions with each other can be traced back more than 400 million years.

Conrad Labandeira, curator of fossil arthropods (insects and related animals) has studied those relationships for much of his career. He recently published a new paper in The Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences with former Smithsonian NMNH Department of Paleobiology graduate student Ellen Currano reviewing the fossil evidence for evolving insect-plant relationships over the last 420 million years.

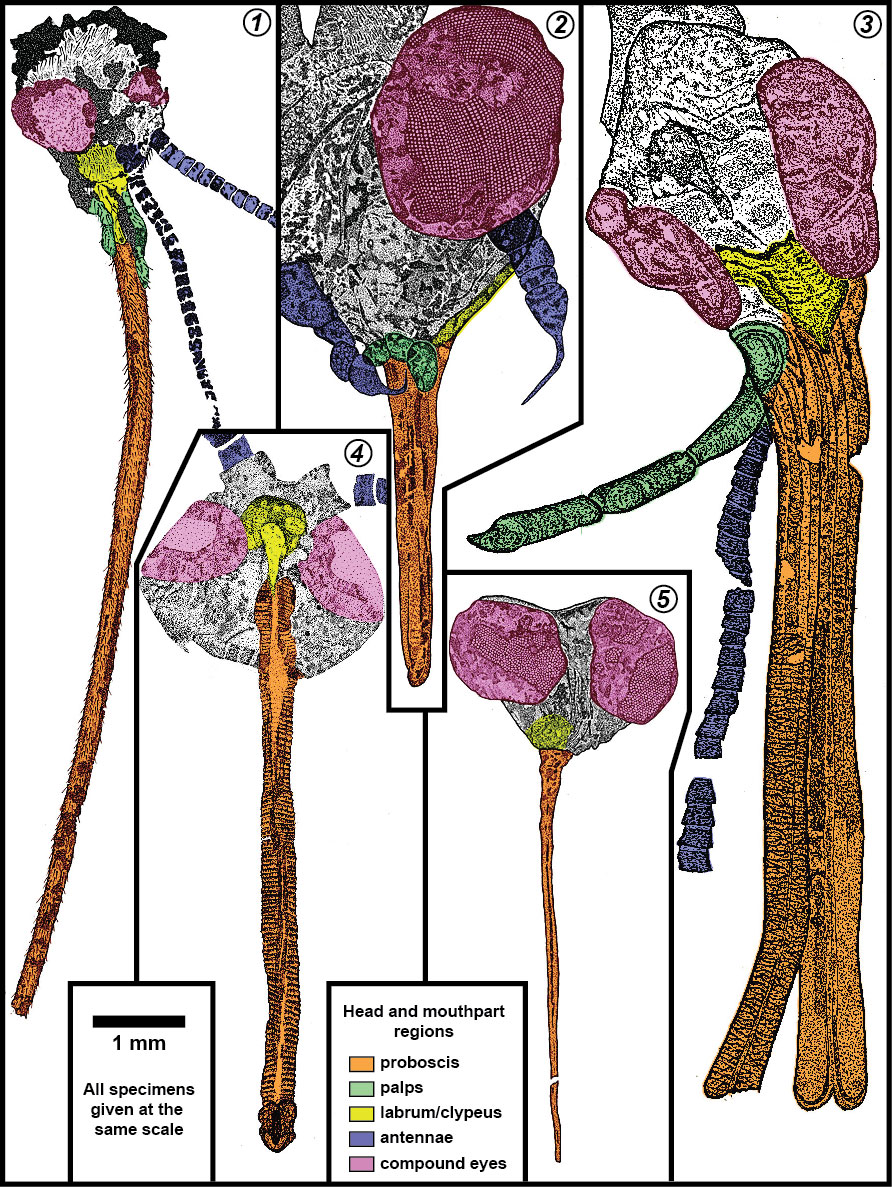

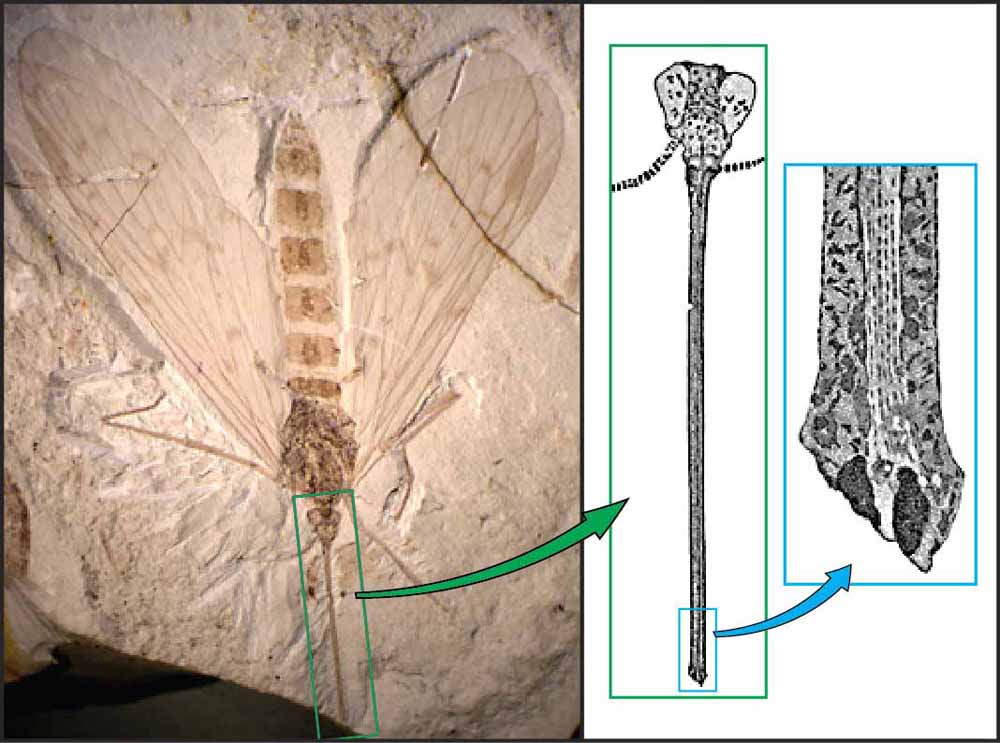

Article continues belowIn the paper, the paleontologists present striking images of insect heads and mouthparts drawn from fossils by Labandeira to illustrate the tube-shaped proboscises which functioned like movable flexible straws, allowing the insects to feed on plant fluids.

This distinctive type of proboscis evolved separately in scorpionflies, flies, lacewings, butterflies, and several other unrelated groups of insects — a phenomenon called convergent evolution.

To make such enlarged and precise renderings of the fine structures sometimes preserved in insect and plant fossils , Labandeira uses a microscope with a special attachment, called a camera lucida. With that setup, he can simultaneously see a magnified image of a fossil and a projected image of the fossil. This facsimile projection allows him to trace the fossil and its tiny features onto an illuminated sheet of tracing paper in a dark room. Enlarged detail ― such as the facets of compound eyes, miniscule mouthpart elements and the hairs that clothe certain regions of the head ― he draws on tracing paper. Then he renders the tracing-paper image into a finished copy using permanent ink on transparent sheet film. That mylar copy can be scanned as a computer file and colorized digitally to indicate important anatomical structures, such as the palps, upper "lip" and proboscis proper. For publication, Labandeira reduces the image with an appropriate calibrated scale to indicate the actual size of the illustrated structure.

To learn more about Conrad Labandeira's research and to access digital versions of many of his publications, visit his research page. To read more about drawing with camera lucida, visit the Smithsonian FossiLab website. For more information about the intersection of paleontology and art at the Smithsonian, visit their Paleo Artpages. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This article was originally published as Drawing Conclusions from Fossil Insectson the blog Digging the Fossil Record: Paleobiology at the Smithsonian.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus