Languages May Be Shaped By Geography

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The way different languages sound may depend on the geography of the landscape on which they're spoken, new research suggests.

A study of more than 550 languages around the world found that tongues spoken in high-altitude regions contain more sounds called ejective consonants, made with a burst of air, than languages closer to sea level.

Ejectives may be more common in these regions because the sounds are easier to produce there, or possibly because they minimize water loss from the mouth in dry, high-altitude environments, said study author Caleb Everett, an anthropological linguist at the University of Miami.

Traditionally, linguists have assumed that geography doesn't play a role in shaping languages, with the exception of vocabulary specific to certain environments or wildlife. A handful of small studies have suggested that languages in warm climates use more vowels than languages in cold climates, but the findings are controversial. [10 Things That Make Humans Special]

Everett set out to investigate how other aspects of geography, namely altitude, might be linked to certain sounds, or phonemes, in a language. Specifically, he looks at ejectives, a class of sounds (not present in English) produced by puffs of air in the mouth as opposed to the lungs. Everett suspected these sounds might be more common at high altitudes, where the lower air pressure would make them easier to produce.

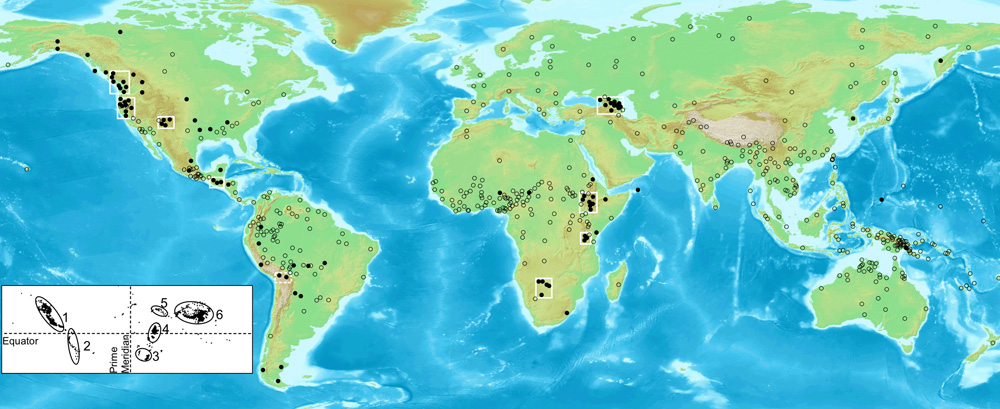

To test this hypothesis, Everett analyzed phoneme data on 567 languages from the World Atlas of Linguistic Structures Online. He compared the data to the altitudes where the languages were spoken, obtained using geographic mapping software.

Languages containing ejective sounds were found to occur at or near five of the six major inhabited high-altitude regions, including in North and South America, southern Africa and Eurasia, Everett found.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The one exception to this pattern was the Himalayan Plateau — that region was not home to any languages containing ejectives. "It is not particularly surprising that one region should present such an exception," Everett wrote in his paper, "and in fact it strikes us as remarkable that only one region presents an exception."

Languages at high altitudes may have evolved to have ejective sounds because less effort is required to produce these bursts of air in thinner atmospheres, Everett speculates. His basic calculations of the air pressure needed to make these sounds support this explanation.

Alternatively, speaking in ejectives might expel less water vapor from the mouth, allowing water to be conserved in typically dry high-altitude environments, Everett said.

Studies are needed to test these hypotheses. "Understandingly, people will be skeptical," Everett said. But in terms of the link between altitude and ejectives, "the data are overwhelming," he said.

The findings were detailed today (June 12) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus