Lung Donor System: How Kids May Slip Through Cracks

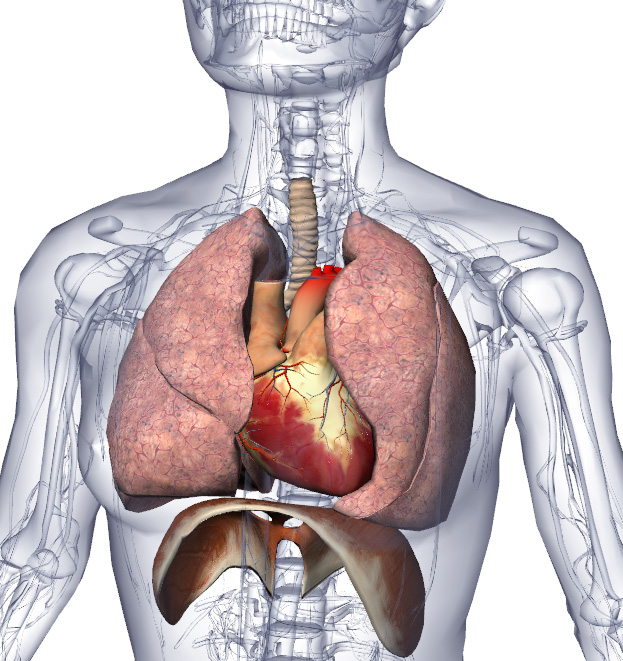

The case of Sarah Murnaghan, a 10-year-old girl with cystic fibrosis in dire need of a lung transplant, has some people questioning the rules regarding how lungs are allocated to children.

Murnaghan, who has just weeks left to live according to her parents, was placed near the bottom of the waitlist to receive a lung from an adult donor because of her age. Her parents, arguing that the allocation rules were not fair to children, sued the Secretary of Health and Human Services, Katherine Sebelius. Today (June 6), a federal judge ruled that the age requirement be suspended for Murnaghan until June 16, although it remains to be seen if an organ will become available to her in that time.

While Murnaghan's case continues to play out, here is an overview of how the system for allocating available lung donor organs currently works:

The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), the nonprofit organization that manages organ donations in the United States, uses a system called the "Lung Allocation Score" to assign lungs to patients ages 12 and up.

A higher score means a patient has a higher priority to receive a lung transplant, said Anne Paschke, public relations manager for UNOS.

The score is based on two main factors: how long a patient would be expected to live without a transplant (the patient's "medical urgency") and how long the person would be expected to survive with the transplant.

These factors are calculated based on a patient's age and body mass index, along with the type of disease the person has, and many other patient characteristics. Research has shown that all of these characteristics can influence survival.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The system works like this: when donor lungs become available, doctors have just two-to-four hours to get the organs transplanted to a patient in need, Paschke said. For this reason, recipients must be within a certain geographical area.

The donor lungs are entered into a database that contains information about patients in need of a transplant, and the database finds a match. The matching process first removes all patients who fail to quantify for the transplant because they are incompatible (for instance, they have a blood type that doesn't match). Then, the remaining patients are ranked according to the UNOS allocation policy, which includes LAS score, Paschke said.

The system for children under 12 years old does not use LAS score, however, Paschke said. When UNOS originally came up with the LAS score, there was not enough research on patients ages 11 and younger to create a valid computer program using this score that would work for children.

Children who need lung transplants are not on a separate "list" exactly, but the matching process includes age. Lungs from adult donors are offered first to patients ages 12 and older, and lungs from children donors are offered first to children 11 and younger. Research shows that children generally benefit from receiving lungs from other children, rather than adults. (Adult lungs tend to be too big to fit inside a child, and patients who receive a partial lung may have lower chances of surivival.)

Because there are very few child donors, young children in need of a lung transplant can wait for long periods. Murnaghan was on the list for 18 months before the ruling.

Children are given priority for a lung transplant if they meet certain criteria, such as requiring mechanical ventilation, UNOS says.

Today, the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (part of HHS) said it would hold a meeting to review it's lung allocation policy on Monday, June 10.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus