Don't Panic, It's Just a Pandemic

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

If it's really something to fear, this flu pandemic seems like it's taking its time.

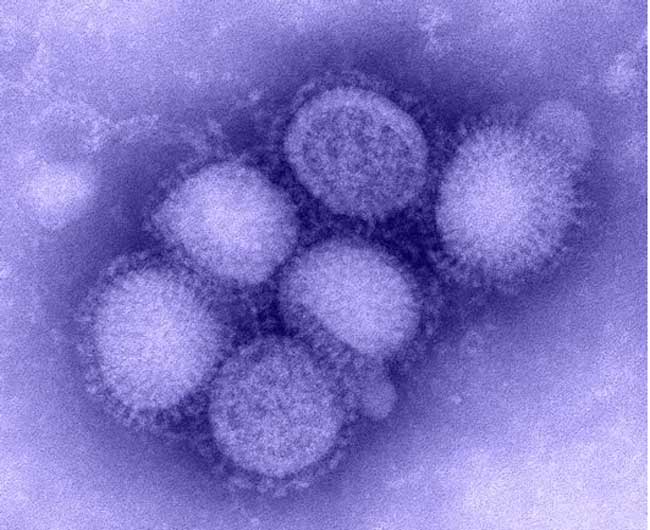

We first heard about "swine flu" in April. Now we're supposed to call it the new H1N1 strain of influenza A.

We first heard that the new flu was wildly fatal in Mexico. Yes, most of the deaths — 108 of the 144 worldwide deaths as of this afternoon, per the World Health Organization (WHO) — so far have been there and every death is a tragic loss, but that nation's overall H1N1 flu fatality rate currently is 1.7 percent.

Worldwide, the virus currently has a 0.5 percent fatality rate. For comparison, perhaps as many as 10 percent to 20 percent of the victims of the "Spanish flu" of 1918–1919 died. It killed an estimated 50 million people in 18 months.

And today, after two months of caution and counting cases, the WHO has declared that this latest influenza outbreak is a pandemic.

At this point, many people may be burned out on the coverage of this flu virus and barely fazed by this new development. Should we be?

What does 'pandemic' mean?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The WHO today elevated its global risk assessment for the new swine flu from Phase 5 to Phase 6, the top of a six-point scale. Phase 6 is a full pandemic — which is defined as community outbreaks in two countries in two separate regions of the world. Phase 5 designated human-to-human spread of a virus into at least two countries in just one region of the world.

There are currently 28,774 cases in 74 countries, according to the latest WHO statistics. (There are 13,217 cases in the United States, with 27 deaths.)

Declaring a pandemic is a big official deal, so big that this is the first global flu epidemic in 41 years (the last one was the "Hong Kong flu" which killed 1 million people). A pandemic is something like a global version of an epidemic, which is a disease outbreak in a specific community or region or population. Health agencies work together worldwide to define the word "pandemic" to avoid controversy over how to make this call, said Dr. George T. DiFerdinando Jr., a physician epidemiologist and professor at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey-School of Public Health. Once there is rapid human-to-human transmission, there is no question that a pandemic is occurring, DiFerdinando said. The 1918 Spanish flu was a good example of a rapid pandemic — it spread in a period of four to six weeks across every state in the United States.

The U.S. government has already taken aggressive action, preparing earlier this spring for what was correctly predicted to be an imminent pandemic. Customs officials began checking travelers for illness upon entry to the nation's territories. Millions of doses of anti-viral and other medications from a federal stockpile are being distributed.

The latest WHO designation triggers officials worldwide to dedicate more money and other resources to victims and afflicted regions.

What's next

There will be a second wave of this flu, Dr. Margaret Chan, WHO director-general, said today, adding that so far this pandemic is "of moderate severity."

"Countries where outbreaks appear to have peaked should prepare for a second wave of infection," she said.

Most Americans and others who've had the new flu say it was mild (by contrast, the regular seasonal flu kills about 30,000 U.S. residents every year). Another question is whether this virus will mutate to become a more virulent killer in the coming months, especially in the winter in the Northern Hemisphere. Flu viruses are known to evolve very quickly.

"We are in the earliest days of the pandemic," Chan said. "The virus is spreading under a close and careful watch … We know, too, that this early, patchy picture can change very quickly. The virus writes the rules and this one, like all influenza viruses, can change the rules, without rhyme or reason, at any time."

Another cause for concern: Previous pandemics typically spread worldwide within six to nine months. The current flu spread worldwide within two months, probably as a result of all the air travel we do nowadays. Germs spread faster and more easily when people travel a lot across vast distances.

The latest trends — flu prefers young

Now that there are some decent statistics on this flu, some other trends are clear, Chan said:

- This new H1N1 virus preferentially infects younger people. In nearly all areas with large and sustained outbreaks, the majority of cases have occurred in people under the age of 25 years.

- In some of these countries, around 2 percent of cases have developed severe illness, often with very rapid progression to life-threatening pneumonia.

- Most cases of severe and fatal infections have been in adults between the ages of 30 and 50 years.

- This pattern is significantly different from that seen during epidemics of seasonal influenza, when most deaths occur in frail elderly people.

- Many, though not all, severe cases have occurred in people with underlying chronic conditions. Based on limited, preliminary data, conditions most frequently seen include respiratory diseases, notably asthma, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, autoimmune disorders, and obesity.

- Around one third to half of the severe and fatal infections are occurring in previously healthy young and middle-aged people.

- Pregnant women are at increased risk of complications. This heightened risk takes on added importance for a virus, like this one, that preferentially infects younger age groups.

- The vast majority of cases have been detected and investigated in comparatively well-off countries. It is unclear if the virus will behave differently and make people more or less sick in the developing world, Chan said.

History of declaring pandemics Back in the 1970s, the general medical thinking was that pandemics occurred every 10 years on average, since there had been a previous flu pandemic in 1968 and another in 1957. The experts were wrong. Until today, there hadn't been a flu pandemic since 1968.

That 10-year thinking is part of what threw medical experts off in 1976 when a swine flu outbreak emerged in 1976 at Fort Dix in New Jersey. The national response to that event taught some hard lessons about efforts to head off a pandemic. The federal government initiated a vaccination campaign — some 40 million were inoculated. But a pandemic failed to materialize. Instead, some people got sick from something else — possibly the vaccine itself (and some of them died). "Predicting pandemics turns out to be imprecise in the medical and public health community," DiFerdinando said. For instance, many medical professionals expected avian flu to become a human pandemic at some point in the past 10 years, but that has not occurred yet. "If you can figure out what the frequency is [for flu epidemics] — you'd be quite famous," DiFerdinando said.

And that helps to explain why the WHO didn't jump the gun on declaring the new H1N1 flu a pandemic. The agency had long ago arrived at a definition of "pandemic" and waited until it felt that the data were in to justify using that word.

- More Flu News & Information

Other Flu Features:

- 5 Essential Swine Flu Survival Tips

- Video – The Truth About Pandemics

- 'Worst-Case' Scenario for Flu Estimated

- Why Are Humans Always So Sick?

- Flu Basics

Robin Lloyd was a senior editor at Space.com and Live Science from 2007 to 2009. She holds a B.A. degree in sociology from Smith College and a Ph.D. and M.A. degree in sociology from the University of California at Santa Barbara. She is currently a freelance science writer based in New York City and a contributing editor at Scientific American, as well as an adjunct professor at New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus