Vitamin C and Ibuprofen May Help Stop TB

Two cheap and widely available substances, vitamin C and ibuprofen, show promise for helping to treat tuberculosis in laboratory models, according to two new studies.

In one study, researchers in Spain found that the anti-inflammatory drug ibuprofen slowed the formation of tuberculosis lesions in the lungs of mice. Mice infected with TB bacteria that were treated with ibuprofen lived longer than mice not treated with ibuprofen, according to the study published online May 3 in the Journal of Infectious Diseases.

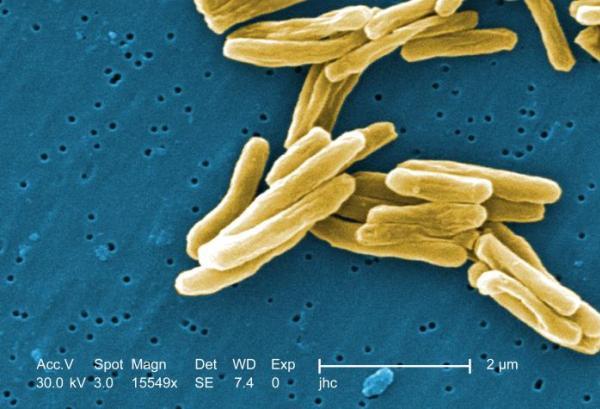

In another study, researchers found that vitamin C killed TB bacteria growing in laboratory dishes, including the strains that are resistant to available drugs. That study was published May 21 in the journal Nature Communications.

Neither vitamin C nor ibuprofen has been tested in clinical trials as treatments for people with TB, and studies in lab dishes and animals certainly do not always hold up in people. But experts say that these findings are important, especially given the high global death toll from TB, and that these compounds are already commonly used in people.

"It's best to think of these strategies for compassionate treatment of dying patients while better drugs are being developed and evaluated in clinical trials," said Dr. Ben Gold, an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College, who was not involved in either study.

According to World Health Organization (WHO), TB causes 1.4 million deaths yearly, killing more adults than malaria, AIDS and all tropical diseases combined.

The standard treatment for TB consists of four drugs given over six months. But for people infected with bacteria that have developed resistance to medication, treatment can take up to two years, and it may fail. Moreover, strains of drug-resistant TB bacteria appear faster than the time it takes to develop new drugs.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Dr. Pere-Joan Cardona, the lead investigator on the ibuprofen study, said that his results suggest that treating patients with a combination of standard TB drugs and ibuprofen might reduce treatment time, and enhance outcomes for patients.

"Nevertheless, we need a clinical trial to demonstrate this in humans, and officially put it in the TB guidelines," said Cardona, who is a researcher at the Experimental Tuberculosis Unit, a research organization affiliated with the Autonomous University of Barcelona, in Spain.

The same is true for vitamin C; the researchers suggest that further research should be done to explore the potential of using it in tuberculosis treatment.

"At the very least, this work shows us a new mechanism that we can exploit to attack TB," said Dr. William Jacobs, the lead investigator on that study.

Anti-inflammatory drugs and TB

In most people, when tuberculosis bacteria invade the body, the immune system keeps the illness at bay, and the infected person does not show any symptoms. However, in about 10 percent of people, the bacteria escape the control of the immune system. They start multiplying in the lungs, and cause damage by forming cavities within lung tissue.

The researchers of the ibuprofen study wondered whether inflammation might be a key factor in the formation of these cavities. The results showed that for TB-infected mice, ibuprofen treatment reduced the number of TB bacteria detected in the organs, and increased the survival of the animals.

Gold said the results are interesting, and that the next step should be to examine the effects of ibuprofen in combination with standard TB drugs. But in the meantime, ibuprofen is a safe-enough drug that it could be given to people who are severely ill with antibiotic-resistant TB, Gold said.

Vitamin C

Jacobs said that his team's discovery of the effects of vitamin C on TB bacteria was accidental. The researchers had suspected that TB bacteria could be killed by pro-oxidant chemicals. Pro-oxidants trigger the production of free radicals, which in turn damage the DNA and can kill cells.

The researchers looked at vitamin C. Although widely known as an antioxidant, vitamin C can also act as a pro-oxidant, depending on its environment. "The combination of TB drugs and vitamin C killed the entire culture," Jacobs said. These effects were seen in a test tube, with carefully controlled conditions that don't necessarily mirror that of the body. However, the mechanism by which vitamin C was able to kill even drug-resistant bacteria could inspire new drugs, researchers said.

"An ideal TB drug would be one that kills the persistent bacteria, both actively growing and dormant bacteria, doesn’t have resistant mutants, and is safe," he said.

Gold said this finding showed that TB bacteria are "highly sensitive to killing by Vitamin C." Researchers should look at whether there is any historical evidence that vitamin C supplementation benefits TB patients, and whether the vitamin C levels used in the study could be attained in people for long enough to treat TB. Toxicity could be a concern with giving people high levels of the vitamin, he said.

Clinical trials?

Developing new drugs for treatment-resistant TB is time-consuming and expensive, with a cost estimated at $500 million, according to WHO.

"It's inarguable that conventional antibiotics will always beat the non-antibiotics in terms of potency and efficacy," Gold said.

However, it takes 10-15 years to translate research into a drug for resistant TB, he said, "if you have a drug that is cheap, safe, and might have potential to save lives, why not use it?"

Gold and colleagues showed in a study published last year that another inexpensive anti-inflammatory drug, oxyphenbutazone, could kill TB bacteria.

Follow MyHealthNewsDaily @MyHealth_MHND,Facebook& Google+. Originally published on LiveScience.