Discarded Embryos to Generate Blood for Transfusions

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Researchers in the UK plan to make what's being hailed as an unlimited supply of blood for transfusions using discarded stem cells found in human embryos, according to news reports.

They'll test embryos discarded from in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatments to find those with embryonic stem cells that will make O-negative blood, which is the one type that can be transfused into anyone without being rejected.

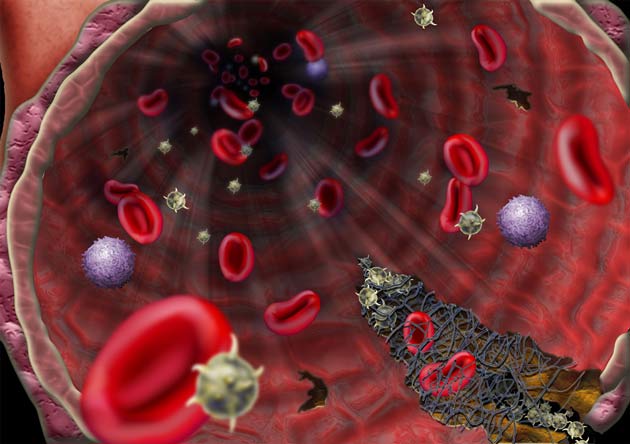

An adult has about 4–6 liters of blood (which transports oxygen through the body), white blood cells to fight infection, and platelets that clot to heal wounds. Many patients died of transfusions before 1901, when the Austrian Karl Landsteiner discovered the human blood types. Landsteiner found that antibodies against donor blood can cause deadly clumping.

Still, supplies of blood available for life-saving transfusions are limited. Local and regional pleas for blood by the Red Cross, owing to critically low levels, have become routine in the past decade. There's more to it all than just giving blood. There are a host of tests that must be run on donor blood to make sure it is free of infection. And blood has a limited shelf life. Blood stored for 29 days or more (nearly 2 weeks less than the current standard for blood storage) is more likely to cause infection in transfusion patients, a study last year found.

Embryonic stem cells have the ability to become all the cells of the body. The idea is that harnessing their power would allow infinite production of what'd being termed "synthetic" blood that would be free of any infections that sometime plague blood supplies.

"In principle, we could provide an unlimited supply of blood in this way," said team member Marc Turner, director of the Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service.

This is no backwater laboratory effort. It's also being supported by NHS Blood and Transplant and the Wellcome Trust, the world's biggest medical research charity, according to The Independent.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 2004, researchers at the University of Minnesota published research explaining the conditions under which blood cell development occurs from embryonic stem cells. But embryonic stem cell research has been somewhat stifled in the United States owing to restrictions on federal funding that were lifted earlier this month by the Obama administration. There may be time to catch up to the UK effort.

"We should have proof of principle in the next few years, but a realistic treatment is probably five to 10 years away," Turner said.

- Embryonic Stem Cells: 5 Misconceptions

- FDA Approves Test to Inject Embryonic Stem Cells into Humans

- Stem Cell News and Information

Robert Roy Britt is the Editorial Director of Imaginova. In this column, The Water Cooler, he looks at what people are talking about in the world of science and beyond.

Robert is an independent health and science journalist and writer based in Phoenix, Arizona. He is a former editor-in-chief of Live Science with over 20 years of experience as a reporter and editor. He has worked on websites such as Space.com and Tom's Guide, and is a contributor on Medium, covering how we age and how to optimize the mind and body through time. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus