Why is grass green?

The short answer is a green pigment called chlorophyll. The long answer is ...

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

As soon as the weather warms, lawn mowers also begin to start up (at least in suburbia), creating those perfectly shaped and brilliantly green lawns. But why is grass green and not blue or purple, say?

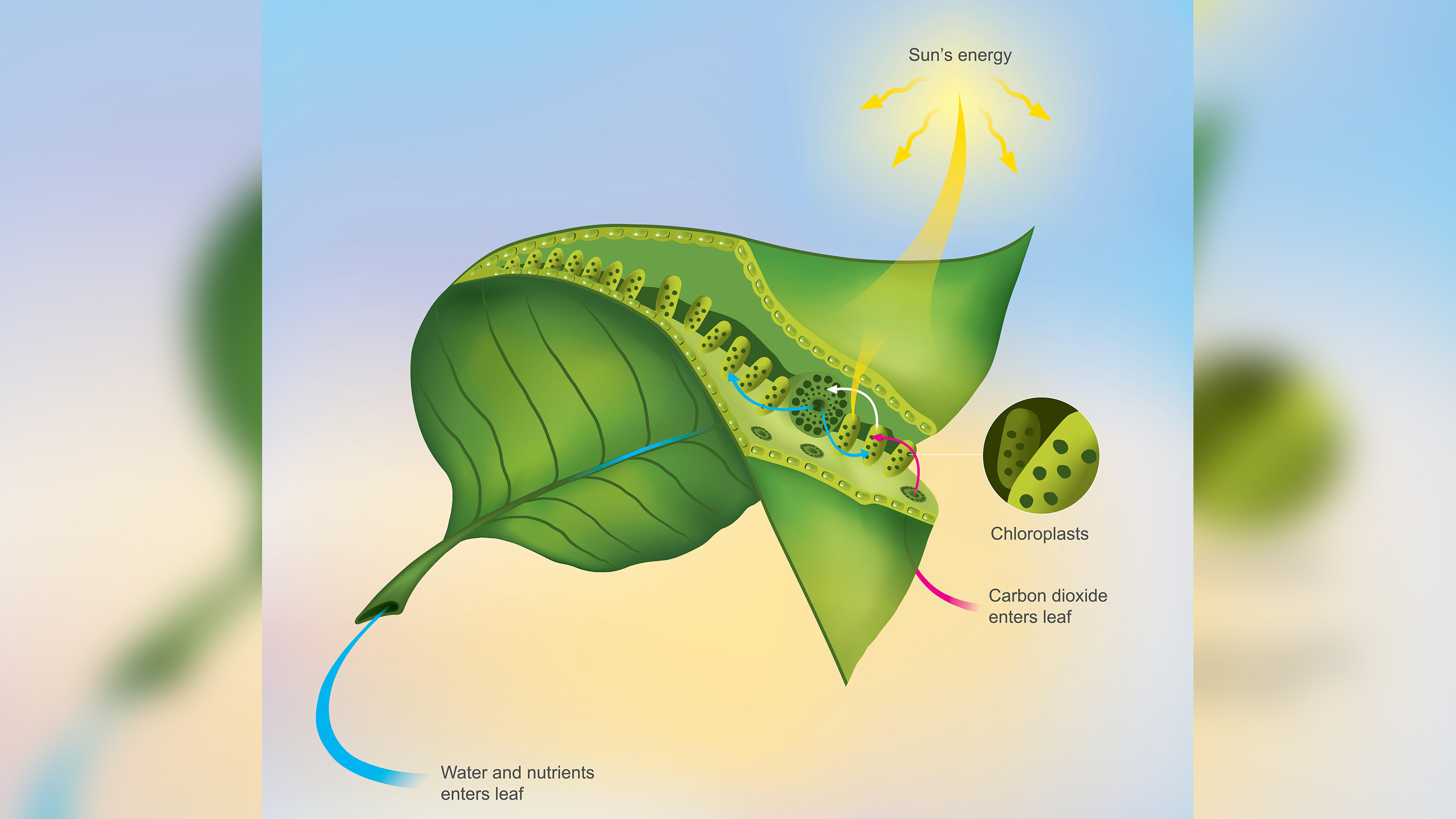

The short answer is a green pigment called chlorophyll. The longer answer has to do with wavelengths and cellular components called organelles and photosynthesis, which plants use to make food from sunlight.

Tucked inside tiny organelles called chloroplasts are molecules of chlorophyll. A molecule of chlorophyll consists of a magnesium ion at its center that is bonded to a porphyrin, which is a large organic nitrogen molecule, according to WebExhibits, an online museum of science, humanities and culture.

Chlorophyll gets its name from the Greek word "chloros," which means "yellowish-green," according to WebExhibits. But how does it make your freshly cut lawn appear a gorgeous green? The molecule absorbs certain wavelengths of visible light, primarily red (a long wavelength) and blue, a shorter wavelength. The green region of the electromagnetic spectrum doesn't get absorbed and instead is reflected, right to your eyes. And voilà — you have green grass.

Related: Do trees exist (scientifically speaking)?

Chlorophyll does more than paint your lawn a verdant hue. It's important for photosynthesis, in which a plant uses the sun's energy to turn carbon dioxide and water into food (in the form of sugars) for growth.

This sugar-making process takes place inside chloroplasts (the same teensy spots where chlorophyll resides). Inside these structures, chlorophyll (and to a lesser extent other pigments) absorb the sun's light and transfer the energy from that light to two energy-storing molecules, National Geographic reported. The plant then uses that energy to turn the CO2 and water into sugars. In combination with nutrients in the soil, for instance, plants can use those sugars to build more green plant parts.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Originally published on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus